The Joint Action Front, (JAF), is beating the drum of street protest from September 16th, 2020. Unlike typical JAF street actions which hardly go beyond one or two spots in Lagos, this is to be a national protest against recent hike in energy costs and Value Added Tax, (VAT).

If JAF musters the capacity to mobilise and put the people on the streets, then the cities of Abuja, Lagos, Kano and Ibadan, amongst others, would transform into interesting theatres of popular action as from midweek.

JAF’s planned action has its significance in that it is coming at a time of elite realignment and consensus about pulling Nigeria from the brink. What that means is that JAF could become the arrowhead of a popular uprising that breaks the long silence in that respect since the January 2012 protest but which was not against the government in power now. Whether JAF has done the kind of mobilisation that can repeat that popular show of force is the puzzle.

JAF’s planned action has its significance in that it is coming at a time of elite realignment and consensus about pulling Nigeria from the brink. What that means is that JAF could become the arrowhead of a popular uprising that breaks the long silence in that respect since the January 2012 protest but which was not against the government in power now. Whether JAF has done the kind of mobilisation that can repeat that popular show of force is the puzzle.

The second observable issue is whether JAF has framed the energy price hike in a manner that illuminates the ontological issues that could fire and sustain popular imagination vis-à-vis a sustained protest. Does everyone automatically understand hike in energy prices to be an act of bad governance? How is that linked to other issues as to warrant resistance politics?

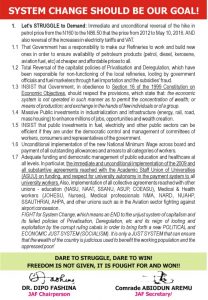

Looking at existing JAF outreach, one gets the impression that it is assumed that everyone understands that the IMF/World Bank is behind the hike and that such would sufficiently anger people. It is possible that JAF is yet to unleash its protest pack and that when it does so, it would come with the sort of leaflets with which the Nigeria Labour Congress, (NLC) not only overwhelmed but so delegitimized the Babangida regime in 1986. Or ASUU’s “my take home pay cannot take me home” master stroke against the same IBB regime subsequently.

Both the radical as well as conservative interests behind the 2012 revolt were not too strong on mass messaging. They were probably too strong in cash power vis-à-vis prolonged popular protest to worry about that but has time stood still?

Popular protest has not been a part of politics in Nigeria but not only is it absolutely legitimate, it also achieves the latent objective of mobilising the citizenry along popular democratic aspirations. In the absence of credible political parties, popular protest should have been the training site in nationalism and patriotic consciousness. Unfortunately, the culture of nationwide popular action has been rare. It is not clear which factors best explains that reality out of the four such plausible explanatory models: poverty of radical praxis; religious predilection of the citizenry; the size of Nigeria and the crisis of nationalism.