President Muhammadu Buhari went to Egypt recently where he announced a visa-on-arrival sort of policy for Africans. It has attracted opposition as well as endorsement from some Nigerians but no notable Nigerian radical politician appears to have said anything substantial on it, either in approval or disapproval. This contrasts sharply with the situation in the mid-1970s. The contrast is important in one respect: the meaning-making problem facing radical politics within and outside Nigeria.

The idea that nothing, including the self, has a meaning prior to the dominant discourse of it at any point in time is still a difficult idea to accept for some radicals and progressives, particularly orthodox Marxists fixated on the materialist interpretation of History. But the evidence from the field must be unsettling for all rationalists, realists, (where Marxism falls) and practitioners of orthodoxy generally. It is in that respect that the contrast matters.

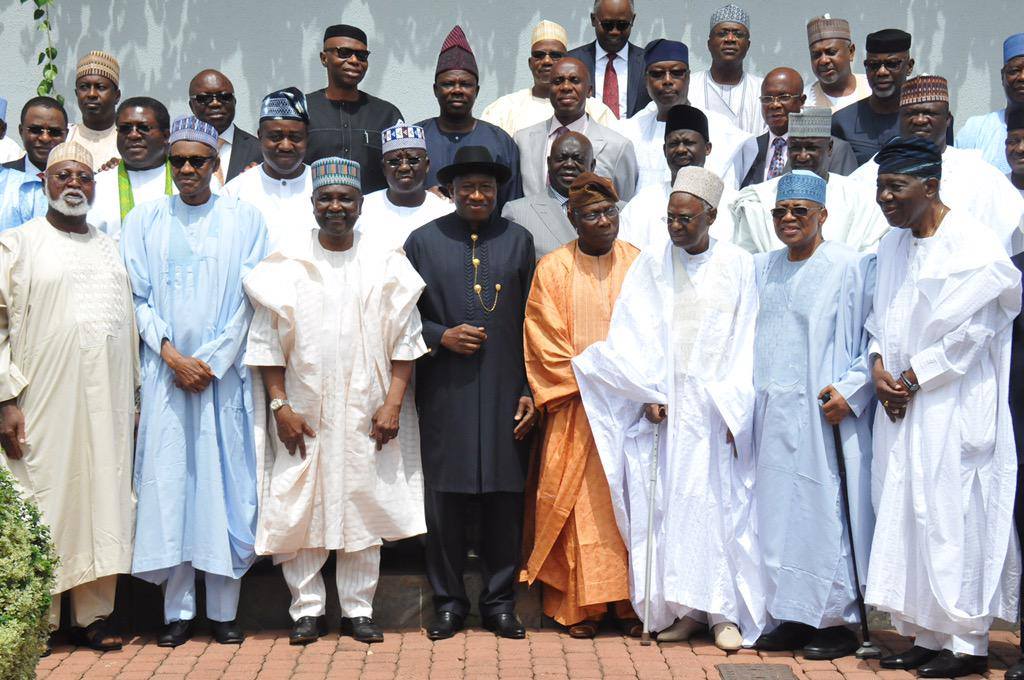

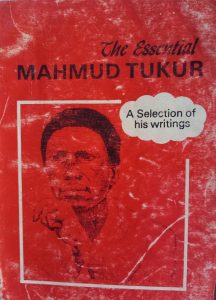

In the 1970s and 1980s in Nigeria, it was hip for progressives or leftists to say, for example, that “The people of Niger are not aliens in Nigeria”. That is the title of a piece by Dr. Mahmud Modibbo Tukur, one of the most solid and sincere radical intellectuals in Nigeria who was, for a long time, president of the Academic Staff Union of Universities, (ASUU). It could be said that Dr. Tukur spoke for all progressives in the short piece now published in The Essential Mahmud Tukur: A Selection of his writings edited by Tanimu Abubakar and published by the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria Press.

In the 1970s and 1980s in Nigeria, it was hip for progressives or leftists to say, for example, that “The people of Niger are not aliens in Nigeria”. That is the title of a piece by Dr. Mahmud Modibbo Tukur, one of the most solid and sincere radical intellectuals in Nigeria who was, for a long time, president of the Academic Staff Union of Universities, (ASUU). It could be said that Dr. Tukur spoke for all progressives in the short piece now published in The Essential Mahmud Tukur: A Selection of his writings edited by Tanimu Abubakar and published by the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria Press.

His 1975 piece was prompted by a statement by Alhaji Umaru Shinkafi who was the Federal Commissioner for Internal Affairs then. As the Minister of Interior, he was directing Immigration officials to curb the “influx of destitutes who continuously come to the country from neighboring countries to beg” and who were becoming a human problem to Nigeria by abusing what he called Nigeria’s traditional magnanimity. Dr. Tukur took umbrage on the statement, saying it amounted to trying to separate Nigeria, Niger and Cameroon that he said were one country before colonialism came. He was surprised that Shinkafi, unlike someone from the interior of Nigeria, could make the statement, emphasizing how physically, historically, culturally and linguistically the national entities were bonded.

In 2019, however, no such categorical position is coming up. Although it is still the same Nigeriens, Cameroonians and other Africans, the current politics of meaning in Nigeria has situated the Buhari pronouncement on visa in a different meaning-making process. The same reality has got a different meaning, in both the conservative and radical camps in Nigerian politics. In the 1970s, the influx of Nigeriens, for example, was seen in official/conservatives quarters in the broad sense of its human problem – begging, refugee congestion, violence, etc. Today, officialdom has shifted to a Pan-African or what looks like a Pan-African framing of immigration or aliens, the discourse that producing the practice of visa at entry point in Nigerian foreign policy.

The radical narrative of aliens has also shifted and very dramatically too. From “The people of Niger are not aliens in Nigeria” in the 1970s, it has moved to a near complete silence from Left circles. Meanwhile, the policy of doing away with visa was a Left initiative, its greatest advocate being the late Dr. Tajudeen Abdulraheem, a leftist of great reckoning and the most systematic voice on African oneness, till his shocking death in 2009. To date, he is still the only person popularly known as the “First African president”, partly a tribute to his singular campaign for African one-ness.

The late Dr. Tajuddeen Abdulraheem whom it would have been very interesting to hear him in the current contestation

The late Dr. Festus Iyayi, another interesting radical it would have been most interesting to listen to in the current situation

How might it have happened that the Left in Nigeria could not claim credit for what one of its own, Tajudeen Abdulraheem, spent so much time promoting? It cannot be other than that the meaning of aliens is now circumscribed by a different meaning environment that even if Dr Taju were still alive, he would have to be very careful and creative in addressing the issue or risk alienating all the camps. It is something that sends a message that foundationalism is dangerous because meaning changes, a change dynamics that does not depend on balance of classes but on balance of discourses. We see that in the dispute over ‘Fulanisation’, for instance.

In the current atmosphere in Nigeria, those convinced that the Federal Government is pushing a policy of ‘Fulanisation’ cuts across classes. Similarly, those who believe that there is no such thing as ‘Fulanisation’ cuts across classes. And it is not even ‘Fulanisation’ itself that is the problem but the meaning of it that each contending camp has. While antagonists of ‘Fulanisation’ see it as a strategy of cultural encirclement, Islamisation and land grab all aimed at power and domination, those who feel framed by the idea of ‘Fulanisation’ cannot stop marveling at the illogicality of the concept entirely. So, it is not ‘Fulanisation’ but the framing of it that is the crisis, meaning that we are dealing with a crisis of meaning.

The ideal thing in this sort of circumstance would be for the Left to come up with the sort of position that will successfully deconstruct both the protagonists and the antagonists and, on the strength of the clarity of Left standpoint therefrom, become the hegemonic ‘historic block’ capable of providing a way out of the face off. However, that is not possible for a Left circle locked in the singularity of working class as the beacon of emancipatory politics since discourses are not class structured but context specific or pragmatic. It is not surprising the world is yet to hear any notable Left statement on ‘Fulanisation’. Yet, the contest of meaning over ‘Fulanisation’ is what is at the heart of the current phase of elite fragmentation in Nigeria, a situation that only Left politics should have been able to diffuse from plausible implosion and the imponderable consequences of such for the working class it privileges. Who will be left to be emancipated if there is a violent outcome which the Left could have neutralized through discursive power instead of being lost in literature of ancient strategies that addressed similar challenges somewhere else in the distant past?

So, how could Marx himself say that change is the order of things but only for some of his apostles to find it so difficult to see that a number of changes have taken place and a number of fundamental shifts have become necessary if the goal of emancipation is to be achieved? It raises the question of which is a greater tragedy for a nation: the ideological unraveling of the Left or Nigeria’s legacy of elite incoherence?