Nigerian journalist, Segun Adeniyi, published his From Frying Pan to Fire in 2019. The strength of that text is in the insider account it provides and, therefore, the gap it fills in terms of a counter-hegemonic framing of the global migration crisis from the point of view of the victims. This has been the most missing dimension of that crisis in that much of what the world knows and believes about migration comes from its representation as a crisis of threat from scavengers, criminals, terrorists, desperadoes and intruders with disruptive potentials to order and stability in prosperous parts of the world.

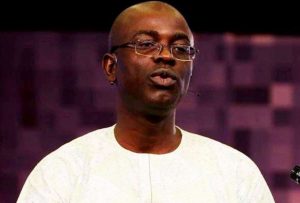

Adeniyi, author of the book in question

Prof Derek Gregory of UBC

Although, there are annoying use of words and phrases such as ‘undocumented immigrants’, ‘help develop Africa’ and the overall economistic tone of the book, not in all cases by the author, the book still provides the stuff with which a serious scholarly African or even a Nigerian statement on the contradictory dialectics of migration could have been made or can be made. The assumption is that those who should know and should make such statement will still re-read the book and do so. Migration in the 21st century has little or nothing to do with the simplistic understanding of it as the crisis prompted by what the late Admiral Augustus Aikhomu called economic adventurers. The analysis developed and popularized in the quarters where manifestations of contemporary global capitalism are taken seriously is that what the world confronts in the migration crisis is the spatial politics of global movement. What the forces and interests that have more at stake to protect have done is a global scaling of subjectivity in terms of who can go to where and who cannot. It is thus more about power through the language game by which some people are constituted as undocumented or not welcome into certain spaces than by their criminal attributes, potential and demonstrated. There is a class, racial, gender and geographical dimension to it.

It is rarely tourists, experts, investors or professionals that are the victims. It is always people vulnerable to the securitising machinery of global hegemons: those who have no formal education and, by implication, no skills or specialization. That is why immigration is a problem but not emigration. Prof Derek Gregory of the University of British Columbia has a beautiful concept for it: territorialisation and re-territorialisation. His concept shares so much with global governmentality.

A Time magazine pix of a fate no longer meted to Africans only in Europe but also within Africa

Buhari of Nigeria and his South African counterpart, Ramaphosa: what’s the narrative?

The South Africans have simply proved the powerful theorist of that powerful university right. Migration is not about undocumented or documented migrants. Otherwise, why would blacks be vulnerable in South Africa where they are symbolic stakeholders? Some power is at work. It is true that the Nigerians export what someone has called the Nigerian DNA everywhere they go to. But the Nigerian DNA has not always attracted a universal response. While some observers of it such as Jerry Rawlings of Ghana insists it is the Nigerian DNA that makes Nigeria the leader in Africa, the London police have a different view. South African blacks have also just manifested a different understanding of it. All these show the limitations of any attempt at explaining migration as a universal problem that arises from economic adventurers seeking exit from troubled homestead in Africa. It might be so but that act in itself can be interpreted differently, depending on where each interpreter stands.

That is what the recent violence in South Africa has done to Adeniyi’s book which has become such a complicated text. On the one hand, Adeniyi’s book provides the sort of details upon which meaning-making is possible from the point of view of those who have had no voice in the framing of the crisis. On the other hand, it submits to the dominant narrative that sees madness in the daring attempt at crossing the Mediterranean to Europe. This imagining of migration is all over the book. Even the title conveys this with the metaphor of fire as an advanced form of hellishness than the frying pan. Both are powerful images of deadend-ness.

Gregory is among those who would echo the new wisdom that Geography is about power through geo-graphing

Warwick University’s Vicky Squire demonstrates that wisdom in this book relation to migration

But migration has not always been this problematic even as it has always been at the centre of the theory and practice of international relations. During the Cold War, it was about stopping people from going out of the Communist enclaves so as to avoid ideological ‘contamination’. The Cold War ended and it became a matter of deploying megamachinism at air and sea ports to determine who should go here and there at a time we are told the borders have collapsed and yielded space to free movement of capital, goods and services and even animals.

Whatever is the case, the problem is much less with Segun Adeniyi. It is doubtful if anyone will deny him a presence of mind in providing a reportorial or journalistic intervention to a major global issue which is rubbing Africa in the wrong ways. What is more worrisome is how there have been no seminars, workshops or reading sessions known to this reviewer on this book. So, what might the media, the military intellectual centres, the Immigration and other border management institutions and the practitioners of that realm have been doing? One may not bet but it would not be surprising if this book is not on the reading list of courses in International Relations, Geography, Cultural Studies, Security Studies, Mass Communications, Political Science and Geopolitics in Nigerian universities. Yet, problematising books and discourses in relation to Nigeria’s self-understanding is what they exist for. If they are doing it, it should not be by murmuring. Let the world hear them!

Nigeria’s voice is missing. It is there in the intellectual, particularly the literary and creative works of Nigerians but it is famished in geopolitical narratives. That should worry everyone because a nation that has no discourse of the world may never be able to penetrate that world no matter the quantum of its quantitative abundance.