It is still a hanging debate. That is the question of which of Literature and Political Science has been more helpful to the African cause. In February 2018 in Abuja, Ibrahim Abdullahi, a Professor of History from the Fourah Bay University in Sierra Leone but also a Nigerian who had been in the US asserted the uselessness of Political Science compared to Literature. He said when African literary giants such as Ngugi (Wa Thiongo) were foreseeing the danger signs emanating from the typical post colonial state in Africa, the political scientists were still “uselessly discussing advantages of one-party statism” or supporting anti-democratic players such as the military. “Political Science is actually a useless discipline. Let’s forget about Political Science”. Unfortunately, Prof Jibrin Ibrahim at whom he directed his attacks had published a paper years back in which he gave African Literature credit for better empirical grip of what was happening. Prof Attahiru Jega who was Chairman of the occasion brought the friendly fires to a humorous close by suggesting a different conference for a fuller debate on which of the two disciplines has been more helpful.

That ‘war’ brought out the relentless and ‘no-nonsense’ attitude of African Literature to the crisis of mission of the typical postcolonial African state. Achebe’s Things Fall Apart took on a subject that is becoming more profound now with the thesis of ‘The Clash of Civilisation’ which the new cover page of the novel dramatises powerfully. With such keen sightedness, African Literature has remained a sustained voice on the ‘African condition’.

That ‘war’ brought out the relentless and ‘no-nonsense’ attitude of African Literature to the crisis of mission of the typical postcolonial African state. Achebe’s Things Fall Apart took on a subject that is becoming more profound now with the thesis of ‘The Clash of Civilisation’ which the new cover page of the novel dramatises powerfully. With such keen sightedness, African Literature has remained a sustained voice on the ‘African condition’.

In this interview conducted by three academics of the Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, a retiring Professor of Literature and a leading authority on Achebe’s literary imagination speaks to various dimensions of that tradition. The interview conducted by the trio of Chijioke Uwasomba, Victor Alumona and Ifenayi Arua, all academics of the Department of English in that university, is part of the book – The Idea of African Fiction – scheduled for public presentation in the university September 13th, 2019. Prof Anyadike has taught for four decades. In the end, it has been a great trek back, touching on the good old days of education, the 1966 coup and how he fought in the Biafran war and what literature can do but why that is not happening in Nigeria. Surely, a great read!. Enjoy:

Q: Where were you born, Prof?

Ans: First of all, I want to thank the team very much for embarking on this project without my prompting. I was born at Igbo Ukwu but I am from Ekwulobia. My father died before I was four years old.

Q: Oh, you are from Ekwulobia! What is Ekwulobia known for?

Ans: Ekwulobia is a town in Anambra State. They say it is the fourth largest town in Anambra state. It has a famous market which draws people like magnet on Eke days. It is centrally located and has a very good environment although it is currently being ravaged by erosion. Ekwulobia shares boundaries with Oko Isuofia, Aguluezechukwu and Nanka. These towns have erosion problems – very great ravines.

Q: What efforts have people like you made to mitigate the impact?

Ans: The little we can do as individuals and as a community is being done, more so as successive governments have been making promises without fulfilling them. The erosion menace requires collective efforts with the government leading.

Q: What was your environment like when you were growing up?

Ans: In those early years – we were three small boys without a father. At times, we didn’t know where the next meal was to come from. I grew up in Aguluezechukwu, my mother’s town. My own village is Ula in Ekwulobia. There are nine villages in Ekwulobia. There wasn’t much development in the town then. I spent only two years in Aguluezechukwu. From Aguluezeukwu I went to live in Ubiaja with my paternal uncle who I followed to Onitsha, Amawbia, Awka and Enugu. It was from Enugu that I proceeded to the Government College at Umuahia.

Q: Who was this your paternal uncle. What kind of person was he?

Ans: He was a perfect gentleman. He did everything to ensure that I went to school. He saw a great promise in me. In all the elementary schools I attended, I came first in class and therefore, he encouraged and vowed to send me to one of the best schools. During the Common Entrance Examination, I selected CKC Onitsha and Government College Umuahia but ended up going to Government College Umuahia.

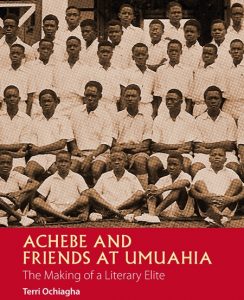

Q: What was Government College like in those days so much so that it produced some of the best literary minds in Nigeria?

Q: What was Government College like in those days so much so that it produced some of the best literary minds in Nigeria?

Ans: Government College Umuahia was modelled after Eton College in England. Rev. Fisher the first principal wanted that kind of model. The school gave you everything as a student. The “big men” of those days sent their children there. The school took in the very best. It also admitted the children of the poor so long as they were bright. It was almost a perfect environment which included great libraries, a golf course with mowers, playing fields, cricket fields, etc. All the best teachers were there. Students came from everywhere – Cameroon, South Africa, etc. What is important in all these is the culture of excellence exemplified in the discipline, well – laid out rules. Nobody dared speak another language other than English. The menu was well prepared. The very poor ones who could not pay were given expanse of land to farm. What they produced was weighed and paid for by the school. It was a beautiful arrangement. The idea of tail-cutting was in vogue. Those in form two considered themselves Lords. The form two students were in charge of the sharing of food in the dining hall. Whatever you were given by the form two boys was what you ate. The form two boys also held away as they initiated the form one students. They used bad and stinging weeds they had crushed to cut your tail. When they realised that we the form one students had used creams to dilute the effect of the weeds on us, they used sticks on us. The tail cutting of my class was the last because I was hit on my left eye and was admitted in the hospital afterwards. I almost lost the eye! Wrestling was also an important sport in the school including other Nigerian games in order not to naturalise Eton in Nigeria. The idea was to train good citizens of the world.

Q: Incidentally, Achebe went to this same school. Did you pick your interest on Achebe while in Government College?

Ans: We heard about Achebe then but he hadn’t become that famous. We didn’t make a big issue out of the name. We read Ridder Haggard and such other stories of the West and how they “pacified” Africans.

Q: Tell us more about the Government College Umuahia. Was it a provincial or international school? Was the school owned by the Government?

Ans: As the name implies, it was a government-owned school. Government College taught me a big lesson. It was in Government College I met people who were much brighter than me. No matter how bright you are, there are people brighter than you (Laughs). Unfortunately we dispersed when the war broke out and we were at home when they began to hunt people to join the Biafran Army.

Q: Before we go deeper into your Government College days and other influences that have shaped your life and consciousness, you seem to play down on your English name.

Ans: I was named Innocent and was known as Innocent. My father was a staunch Catholic. He was one those who set up the church in Ula-Ekwulobia. I was a good Catholic in my early years. People used to make comments about my name. As I grew up I had personal worries about my name and my religion. I didn’t drop it but I silenced it. I started thinking about why people bear names they do not know their meaning. Names should mean something to the bearers.

Q: At what point did you become interested in studying literature?

Ans: It was during the years after my higher school. The brightest boys were encouraged to go and study the sciences. We did as many subjects as we wanted to do. I did well in Geography and Chemistry. While in Government College there were two big libraries – one for the junior classes and another for the higher classes. I read a lot of series in Government College. I enjoyed reading as a student. I read widely. By 1966, I had finished my secondary school education. That was before the war broke out. In those days they selected the brightest boys to do their school certificate examination in form four, that was how we ended up doing our school certificate in 1966 and went back for higher school in 1967. At the end of the war, I went to Lagos to stay with an Uncle. My fraternal uncle’s son had studied Medicine in Hebrew University in Israel, and encouraged me to prepare for university education abroad. I got a small job in Exams Success Correspondence College and later Drum Magazine. I found it useful going to a library at Ebute-meta devouring books and I encountered big names. My maternal uncle in Lagos encouraged me to go to a Nigerian university. Given my readings, I decided to study English ending up specialising in Literature. When I came to Ife, I had the opportunity of meeting Prof. Akiwowo who was then in the Department of Sociology. Because I was being pressured by friends and family to go for a “professional” course I told him I wanted to study Sociology. And when he asked me what Sociology was, I was blank. He then asked me to go and do what I had been given admission to study (English). As I earlier said, I had read a lot of books before coming to Ife. I read The New World of Philosophy in 1972-74. It is a book that deals with all branches of Philosophy. It was one of the books that changed my life. I also found and read books on religion. Dietrich Bonheoffer’s book on religion touched me a lot. He also wrote Letters and Papers from Prison. I read other books that are generally on society and life.

Prof and wife: From a subaltern in a rebel Airforce to a Professor. Yet, such is life!

Q: What role did you play during the Nigeria/Biafra war? Can you refresh our memory to what you think caused the war?

Q: What role did you play during the Nigeria/Biafra war? Can you refresh our memory to what you think caused the war?

Ans: We dispersed from Government College when the war broke out and I was at home when soldiers began to hunt people to join the Biafran Army. I joined the Biafran Airforce and since I had nothing to show that I had a school certificate I was recruited as an Airman into the Air Traffic control unit. I was taken to Uga Airport. We were made to prepare an airstrip at Uli. Our job was to put palm fronds in addition to providing cover for the airport. My Airforce number was BAF 0255. We were not issued with any uniform. It was tough and we were responsible for what we ate. From Uga we were moved to Ntueke Uruala. Behind us at Ntueke was where Chief Obafemi Awolowo was kept having been convicted of treasonable felony. After the war in 1967, I went back to Government College by trekking from Ekwulobia to Umuahia.

Q: What next after the completion of your Higher School programme in Umuahia?

Ans: From Umuahia after my programme I moved over to Lagos

Q: Was there really a pogrom against the Igbo?

Ans: Nobody knows the truth. There are no accurate records. While some people think that there was a pogrom, some others think differently. May be if there is evidence, that proves it. What is pogrom? You may not know the numbers – it is a tricky thing because whoever is pronouncing may have his reasons. What is clear is that so many hundreds of thousands of Igbo people were killed.

Q: Did you ever meet any survivor of the pogrom?

Ans: No.

Q: Why do you think that the narrative of the 1966 coup changed from being national to an ethnic coup?

Ans: The only thing available was what we heard. As young people we heard a lot and later the evidence that the likes of Ademoyega and Ifeajuma provided points to a nationalistic affair. The evidence of Achebe was from what he heard from Okigbo. The coup began as a nationalistic coup and ended with confusion. There happened to be more non-Igbo speaking officers and men killed during the coup.

Q: Nigerians seem not to pay much attention to Major Ademoyega’s Why We Struck in their explanation and understanding of the 1966 coup?

Ans: Most people do so because they are affected by what they see and not intention of the plotters. Intention is one thing and actual execution is a different thing. As human beings, we pay attention to what happens to us.

Q: How well or otherwise has African literature engaged the African condition?

Q: How well or otherwise has African literature engaged the African condition?

Ans: This question is indeed at the heart of the matter. I have spent about four decades of my life interrogating this question. We should not dwell much on how many people who on their own pick up literature books to read. How many people read literature books? People are forced to read these books to pass examinations. Not many people are reading them by choice. Literature has had limited power in terms of changing the African condition. How do we get people to read on their own to develop love for literature?

Q: What is the cause of reading apathy?

Ans: There are many factors. One is the fact that people decide to take short cuts to pass examinations. Another factor is the nature of the society – people prefer to make money. The innate love to read literature is not there. Again, society does not encourage the children to read. If parents read together and get them to absorb the right values, they will read. Literature makes people to become different kinds of human beings, because it has the capacity to impact on values. My haunch is that the habit of reading is not inculcated on children. Rather the get-rich mentality has taken over. Human beings love stories and so children need to be schooled into reading early in life. Telling stories is a natural phenomenon. People are pursuing other things.

Q: What is the value of literature to the society?

Ans: Literature imbues society with the needed values. Child psychologists; sociologists acknowledge the value and concerns of stories. Stories elicit many concerns. Literature is so important that in other climes it is highly promoted. In other places that have developed, serious attention is paid to the study of literature. In Cornell, (Cornell University in the US) at the beginning of each session, the university selects one literary work that every student must read which might be discussed. In 2005, while in Cornell, Things Fall Apart was chosen. That is the kind of awareness that the people who know the value of literature encourage. It is not just literature but the arts in general. When the orientation of the society is not trained, it becomes difficult to do the kind of thing we are talking about. The reading culture is not there at all.

Q: African intellectuals are making waves all over the world but Africa is still in the doldrums bedraggled by all sorts of negativities. Is it that they have not done enough?

Ans: The answer is alienation. The intellectuals you are talking about – the crucial question is – what kind of intellectuals are we? I can’t go to my village and engage seriously with the people. Our education takes us away from our people. Many things are missing in my Igbo cultural life. The bottom line is that I am alienated by my education from full cultural life of my people. It is not that the intellectuals are afraid of their people, but they were not educated to hold up and develop their cultures. In search of the Golden Fleece, we have become alienated. There should be a symbiotic relationship between the intellectual and his/her society. The job of the intellectual is to help project the identity of his/her people. Many of them have been educated away from their people. Your job as an educated person should be to help them project and develop their identity.

Q: Alienation is on two levels: in pursuit of excellence in education you appear to have alienated yourself from your people. In another way, your people also see you as not measuring up because of your level of material condition even with your education. Is that not so?

Ans: It doesn’t capture it in all its entirety. It is only a simplification of it to say that educated people are not respected. Education gives a higher perspective. Money talks in some sense but deep down, education endures. The African intellectuals appear to have failed because they have disconnected themselves from their people. In places like Japan and China, for example, their intellectuals are trained to change their people. We have not decolonized our minds and our classrooms. To be part of the change that our society requires, we need education that will work on the people to abandon the things that are not necessary. I am not talking about superficial education. These intellectuals we are talking about are still looking at the colonialists. Our lawyers still use wigs. Our laws, institutions and philosophy, etc. are products of colonialism. Intellectuals coming from this kind of education cannot develop our society. The main line of my career has been towards decolonizing of minds. Do we develop our society by appropriating and promoting what do not belong to us? I am interested in how minds can be decolonised. If you think that nothing good comes from your culture, you cannot develop your society.

Q: From the way you have been talking, would you mind telling us what influenced you?

Ans: My great influence, among other experiences came from Rev. Father Maduka who, in spite of his religious calling, had so much respect for the Ekwulobia culture that he took the Ozo title of Ekwulobia. Don’t discount the culture. That is the message of Father Maduka. For about five hundred years, great harm was done to our psyche. Our people were treated like animals and sold like articles of trade. The ports of embarkation in Ghana and Senegal show how human beings were stocked like books in shelves.