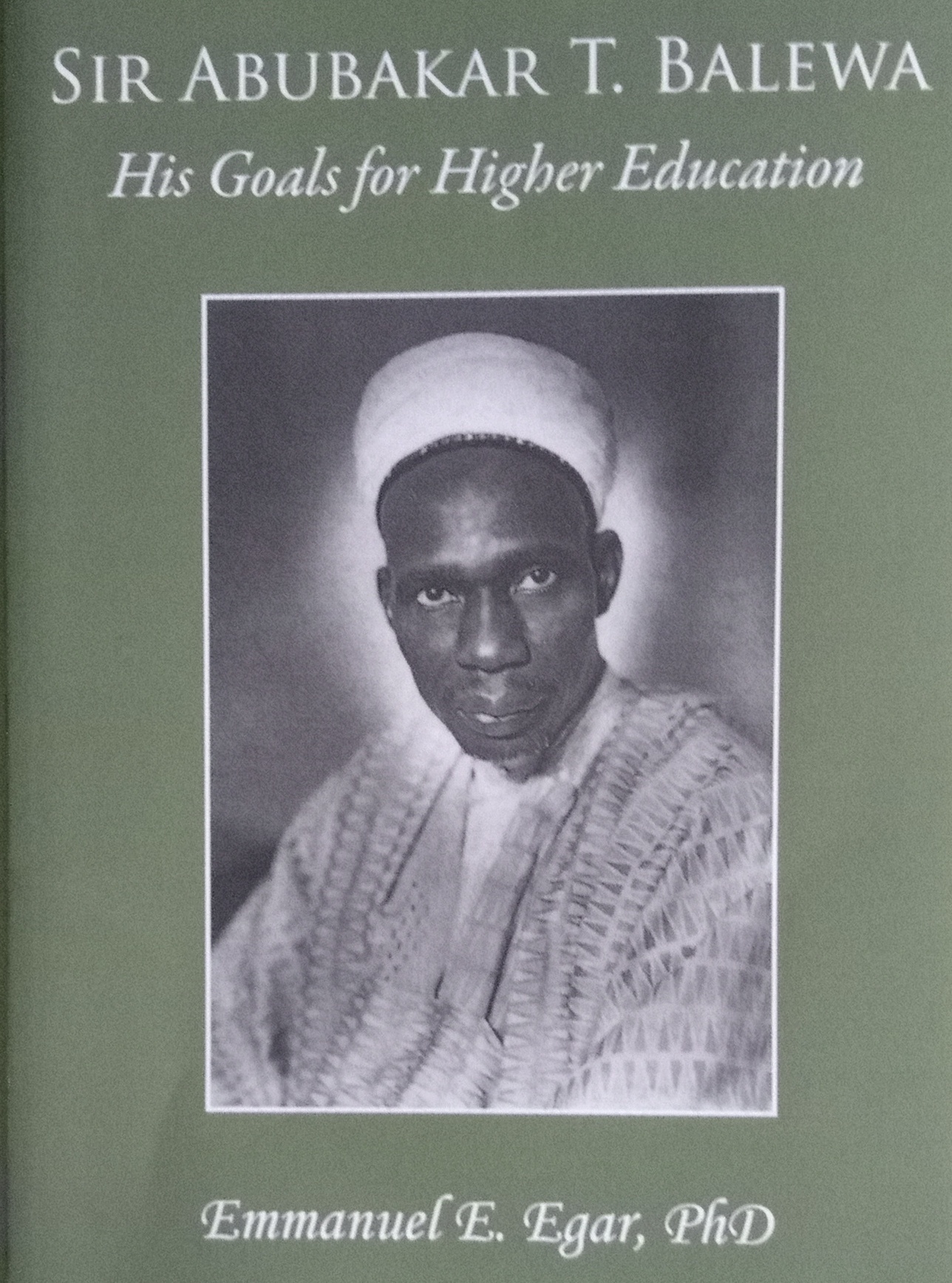

This must be the shortest of any biographical works on Nigeria’s first and last prime minister but, certainly, the most philosophically turbulent of such works on “the golden voice of Africa”. The book and what it chose to focus on brings to life the late prime minister’s capacity to isolate and warn against what he could perceive to be the trouble spots of nation building for the then new nation called Nigeria. That he warned against tribalism and against corruption and called for a root and branch reform of the Native Authority system in much the same manner as Mallam Aminu Kano are fairly well known. That he isolated what could befall the universities is not that known. The uniqueness of this booklet is the author’s perceptiveness in going back to the text of Balewa’s Inaugural Chancellor’s Address at the University of Ibadan in 1960 and put it on the table of crisis management in relation to the remaking of the university system.

A previous biographical work

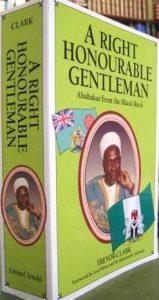

Biographical too!

In other words, this is not a conventional biography of the late leader but certain to be the most powerful sketch on the least known aspect of this man called Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa, with particular reference to the title of his more voluminous biography: A Right Honourable Gentleman: The Life and Times of Alhaji Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa.

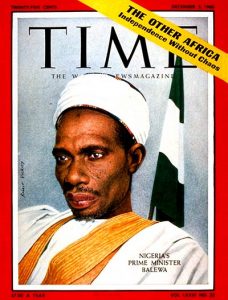

Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa is one of the only four Nigerian leaders that the media and everyday scorecards remain generally favourable to. Three of them died in office and these are Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa; General Murtala Mohammed and Alhaji Umaru Yar’Adua. The fourth one is Nnamdi Azikiwe although he did not die in office. Until recently when the Northern radicals went quiet, the Sardauna of Sokoto was never spared of potshots, especially at the then Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, (FASS), of the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, one of his legacies. Besides the fire from Northern radicals is the fire from other quarters and centres of power in Nigerian politics against the Sardauna. But the Sardauna’s fate is also Chief Obafemi Awolowo’s fate. In spite of regional reverence for him, tendency politics in the Southwest of Nigeria as well as political opponents from other parts of the country exposed him to relentless criticism until his death when some of his sharpest critics became his most sincere assessors. General Sani Abacha, the other leader who died in office, shares an even worse faith. Death in office has not given him reprieve from sundry labeling.

What this background suggests is that death in office is not a definitive reason why some past Nigerian leaders are spared and why some are not spared. And that although those criticised are not automatically very bad leaders, those who are spared must have been so treated because they are perceived to embody potentials in elevated leadership that the nation is appreciative of even as it did not experience it as fully as they would have wished.

This appears to be what this literary philosopher tries to situate in this short book in which he isolated Balewa’s Inaugural Chancellor’s Address at the opening of the University of Ibadan in 1960. There is something of intellectual sharpness in doing that because both the University of Ibadan and the year 1960 have historical significance for Nigeria. To, therefore, make that address as the subject of critical appraisal in relation to the prime minister’s political personality, educational strategy and the idea of the university at a time the university system is generally accepted to be in shambles in Nigeria is a great offering.

No less significant is the continental import of this booklet. Earlier in January 2019, the US based Journal of Education & Social Policy published this reporter’s academic review titled “50 Years After, What is Still Left of Nyerere’s ‘Education for Self-Reliance’? And what does anyone reading Balewa and Nyerere find them to be saying? They were all problematising the received educational system and advocating the nationalization of content and indigenization of the organisational format.

Now back in Nigeria & current HoD, Dept of English, Veritas University, Abuja

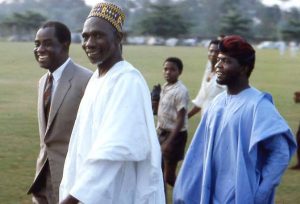

A pictorial insight to Balewa at UI with Prof Onwuka Dike, the first VC

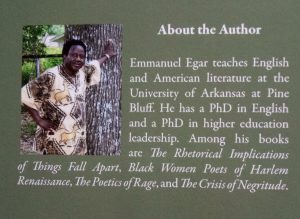

This is why it is a big deal when Dr Emmanuel Egar, the author of Sir Abubakar T. Balewa: His Goals for Higher Education then says in the book that, in the Inaugural Chancellor’s Address, Balewa poured out his heart, “his anxieties, frustrations, doubts, hopes and even desires”. And more so when he also adds that “Balewa wished that our civilisation would not be consumed by its own discontent”. Tragically, that is exactly what has happened as it is found out now and then that university graduates are part of the counter-cultural industries such as kidnapping, cultism, banditry and armed robbery. What sort of knowledge did the university give to them that they could not see those realms to be too far below their dignity, no matter how bad things might be?

What is, therefore, at stake in this booklet is the question of how come Balewa who went to no Oxford or Harvard could produce such a far sighted and nationalist insight but not the generation who have gone to the most reputable universities and centres of reflection in the world? How did it happen? The puzzle is, indeed, puzzling. Recently, The New York Times carried a story on one of the global record holders in architectural design. It turned that the Obafemi Awolowo University, (OAU), Ile-Ife was designed by the outfit. That is as early as the First Republic. The story is told of how the late Sardauna just waved his hands as a measure of how much expanse of land was available to the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria at take-off point. Zik had been a resident student in American universities and it was not surprising that he gave priority to the university idea. But not an Awo, a Sardauna and not a Balewa whose route was not the Zik’s. So, how did it happen that the First Republic leaders were that advanced that the generations after them cannot even maintain what they established?

This is another plank of this short but powerful booklet which does a lot of credit to the author, his own education, the university where he teaches now – Veritas University, Abuja after his patriotic re-location to Nigeria from the United States and to the memory of the late prime minister. What remains to be seen is how various stakeholders to the Balewa legacy of leadership and voice of moderation can stand on this book to not only project his name but also make a statement on the remaking of university education in Nigeria. It is in this sense that this is a required reading for all political parties, ministers, governors, education administrators, critics and sundry book lovers.

It is in doing so that they will discover the depth, the foreboding, the tasks assigned and the challenges foreseen about the university system and nation-making, a project Nigeria has not been very successful at. This is what is in stock from page 3 to page 43. The remaining pages, (44 -101) are taken up by issues peculiar to a prisoner of spatial imagination as a Dr. Egar, connecting Balewa to the Lagos City space and to ‘the Sounds of Silence’. Can you beat that?