By Adagbo ONOJA

The frightening rate at which the smaller parties completely disappeared in terms of self projection as well as the way presidential candidates and their communication strategists fretted, fumbled and went into overdrive in trying to get it right makes this question important: what moved people to vote the way they did in the February 23rd, 2019 presidential election in Nigeria? Was it their class interests, hatred for or disposition to corruption or was it their culture/identity or probably a combination of all of these? If it was a combination of each, how was the combination achieved? President Muhammadu Buhari and Atiku Abubakar are used throughout the piece to exemplify the cases in question, not in oppositional terms.

They voted according to class interest is what most classical Marxists and revolutionaries would say. By implication, there was a preference for President Buhari of the All Progressives Congress, (APC) by the masses as opposed to Atiku Abubakar of the People’s Democratic Party, (PDP) who acted as the voice for neoliberal globalisation throughout the campaign. Atiku was certainly articulating the case for privatisation or what David Harvey calls “Accumulation by dispossession”; foreign investment and little of government. His Vice-Presidential candidate even went as far as calling China a private sector led economy which was a communication disaster. So, a claim of the class character of the voting looks like something that can be defended.

A manifesto for ‘accumulation by dispossession’ by implication

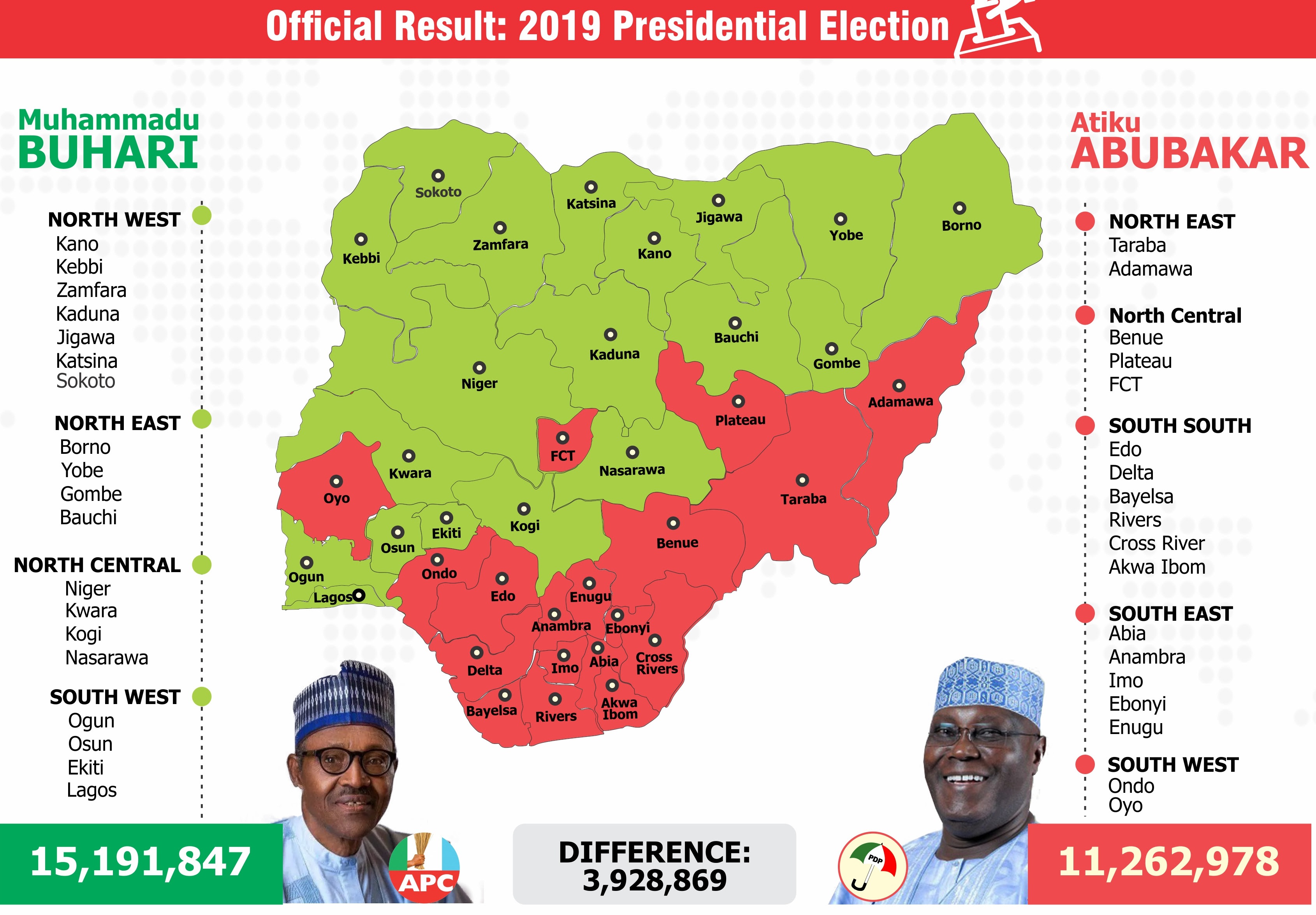

But, that is only if Atiku Abubakar did not get any votes from among the same masses. Broadly, it is 15 million for Buhari and 11 million for Atiku. 10 -12 million votes is what Buhari was getting when he was contesting between 2003 and 2011, meaning that what Atiku has got is not dismissible as too marginal as for his own share of the masses to be discounted. This puts at risk a claim of class character of the voting pattern since majority of those who voted for Atiku are also members of the class of masses. Except if we say that the masses who voted for Atiku were suffering from false consciousness but when is consciousness false or true? All consciousness are situational and the claim of false or true consciousness can only be a product of the materialist cum rationalist cant. Conclusion: traditional class analysis will not hold in explaining the voting pattern in the February 23rd election.

Was it then corruption? That is to say that all who voted for the president hate corruption while those who did for Atiku Abubakar have no qualms about that. There can be no denying that the PDP did not take fighting corruption seriously. But who is in the APC that was not in the PDP? Only very few except if we are reckoning with Adams Oshiomhole’s statement that as soon as one crossed into the APC, one’s sins were forgiven.

It was learnt that the tag of corruption on anyone could be a serious issue in the Muslim North because Shehu Usman Dan Fodio and the other intellectuals of the Jihad so frowned at corruption in their leadership codes as to have left behind terrible images of the corrupt. The explanation is that it goes deep into popular psychology against whoever is successfully framed to be a paragon of the corrupt. A foremost traditional leader from the Caliphate compared a corrupt person to a dog in 2015. The problem again here is how no less than 7 out of the about 15 million who voted for Buhari have no experience of the Caliphate imagination of the corrupt person. Rather, they have completely different mental picture of who or what is corruption. So, to stick to a claim that hatred for corruption was a factor in itself would be the same as answering the question of what drove the non-Muslim Northerners to vote for Buhari but would not move those of them who didn’t vote for him?

At this point, it is more reasonable to say that it was not hatred for corruption or disposition to it but the power over the interpretation of the facts and figures of corruption. In other words, both Buhari and Atiku were beneficiaries/victims as the case may be of narratives of corruption rather than corruption itself. By narratives, we refer to each’s careful arrangement of the facts of corruption in his own favour throughout the campaign. What each was saying was neither the truth nor the lie but an effort at constituting reality of the issue in question.

Sultan of Sokoto

If classical class analysis and corruption did not decide the election, did identity do it? The link between the Caliphate anti-corruption value codes mentioned earlier would suggest that culture is what did it. Igbos, theorized Olusegun Obasanjo, hate poverty. That is why, he said, they were heading for Atiku/Peter Obi rather than Buhari whom he said was good in unleashing misery. On the other hand, it was consistently said and it came to pass that the Northwest was voting Buhari. The Northeast was being told in no uncertain terms that they must vote for their son. Buhari who won got so much of the his votes from the Northwest but just as he also got plenty from the Southwest, the Middle Belt and even the Southeast and South-south. And he got figures substantial enough in each of these places as to make any totalizing claims nonsensical. So, can culture be a plausible explanation for the voting in the presidential poll? The answer is No. if neither class nor corruption and certainly not culture, then what happened? How might the result be explained?

It cannot be over repeated that the world itself has provided no terms or words or concepts by which human beings can understand and act on it. It is human beings who ended up providing the terms or words by which the world is understood and acted upon. What this means is that what decided how people voted has very little to do with class, corruption or culture in their universal senses but only in their specific, contingent senses. It is thus the re-arrangement of each of these concepts and many more other concepts along the binary code of good versus bad/acceptable versus unacceptable for each of the voters that explains the voting pattern. It is true that the Southeast or the Southsouth voted massively for Atiku as against Buhari but to stick to an ‘Igbo voting pattern’ explanatory model could turn out a totally hopeless claim if there is a careful study of why each voter of Igbo identity voted the way he did. This analysis must be true. Otherwise, we would not be able to explain why some Igbos, in some cases in one village or town or settlement, voted for Buhari rather than Atiku or even not for any of the two but Kingsley Moghalu or whoever stood on APGA platform and so on.

There is really nothing new in saying that class, ethnic or locational homogeneity is lacking in nuance, with serious implications for nation making in contemporary Nigeria. What is new is how it is only recently that the inadequacy in that is being exposed in favour of the paradigm that nothing makes sense in itself but only in relation to something else. And if that is the case, then reality itself is how the real is represented, not what it might be. This corruption in itself does not exist but as a derivative of its representation. Hence, the implausibility of Buhari and Atiku having the same sense of corruption.

As in politics, so is it in war where the power of Hollywood and that of technology has created the MIMEC, (military-industrial-media-entertainment-complex) as opposed to the MIC, (military-industrial-complex) that we all know. With MIMEC, war can be spoken of as hygienic campaigns where killing and death becomes entertainment. It is not as if war can ever be painless or death free but in the first Gulf War, ‘CNN’ suggested that the bombs were so smart that they could even choose who to kill and who to spare. And where mass death could not be covered up, then they say it is collateral damage. It is all about the reality that comes from use of language within a given structural and institutional context.

As in politics and war so it is in sports, business, diplomacy and everything else. Party headquarters, militaries, big businesses, government houses and other players who ignore this ‘linguistic turn’ do so at their own peril. There is no such thing as class or corruption or culture or identity or whatever it is outside of ‘what we make of it’.