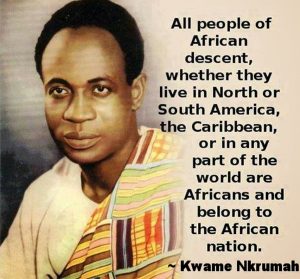

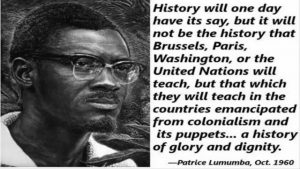

They were so feared that they had to be eliminated or incarcerated: Patrice Lumumba, Kwame Nkrumah, Nelson Mandela, Samora Machel and so on. Physically dead and gone to their graves, these radicals are, however, still the icons in African politics. In this piece, for instance, the writer celebrates Africa joining hands with the people of Burkina Faso last October to celebrate the life and work of Captain Thomas Sankara, assassinated but not forgotten leader of that country 31 years ago. The piece was first published in this link: thisisafrica.me/sankara-an-upright-man-in-a-sinful-world/

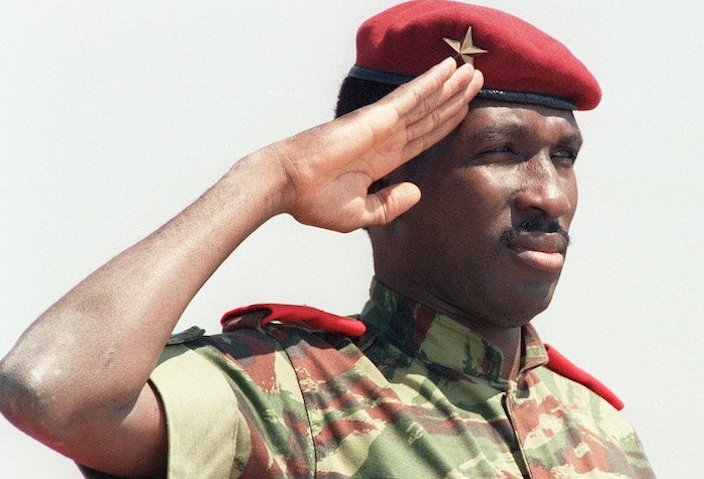

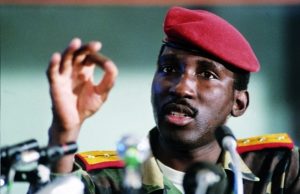

Many nationalist leaders took up frontline roles to liberate their people from colonialism, regardless of the life-threatening conditions and consequences that prevailed at the time. African people were facing harsh conditions in their homelands due to colonial domination and exploitation. North of Ghana’s border is Burkina Faso, a country that owes its birth to a young, selfless and dynamic Pan-Africanist leader, Thomas Isidore Sankara. He was the leader of Burkina Faso’s revolutionary government from 1983 to 1987. To embody the new autonomy and rebirth, he renamed the country, changing from “Upper Volta” to “Burkina Faso”, which means “Land of Upright Men”.

Many nationalist leaders took up frontline roles to liberate their people from colonialism, regardless of the life-threatening conditions and consequences that prevailed at the time. African people were facing harsh conditions in their homelands due to colonial domination and exploitation. North of Ghana’s border is Burkina Faso, a country that owes its birth to a young, selfless and dynamic Pan-Africanist leader, Thomas Isidore Sankara. He was the leader of Burkina Faso’s revolutionary government from 1983 to 1987. To embody the new autonomy and rebirth, he renamed the country, changing from “Upper Volta” to “Burkina Faso”, which means “Land of Upright Men”.

In an interview, Ernest Harsch, the biographer of Thomas Sankara, paints a vivid image of the remarkable personality of this legendary African icon:

He did not like the general pomp that came with the office. He was interested in ideas. He’d think for a while, then respond to your questions. In terms of public events, he really knew how to talk to people. He was a great orator. He loved to joke. He often played with the French language and coined new terms. He often made puns. So, he had a sense of humour. In Burkina Faso, you’d see him riding around the capital on a bicycle or walking around on foot without an entourage.

Such was the affability and the humility of Sankara. On 15 October, Africa joins hands with the people of Burkina Faso to celebrate the life and work of this great African icon. The continent celebrates his unwavering commitment and dedication to the resistance of the continued oppression of the Burkinabe people by the colonial authority of France.

Sankara is also remembered for the strides he made to develop his country in areas of education, health and gender empowerment, as well as his fiery desire to eradicate corruption and its effects. This article highlights the legacy of Sankara, with a clear reflection of what he stood for in his lifetime. Juxtaposed with the life and legacy of this illustrious son of Africa, the last section looks at the general bankruptcy of leadership in Africa today.

Exactly what did Thomas Sankara want for his country?

President Paul Kagame of Rwanda is still difficult to categorise in that although he has brought development to Rwandfa, it is at the expense of democracy. Are development and democracy antagonistic for societies in transition?

Noel Nebie, a retired professor of economics, told Al-Jazeera: “Sankara wanted a thriving Burkina Faso, relying on local human and natural resources, as opposed to foreign aid, and starting with agriculture, which represents more than 32 percent of the country’s GDP and employs 80 percent of the working population. He smashed the economic elite who controlled most of the arable land and granted access to subsistence farmers. That improved production, making the country almost self-sufficient.”

As an ardent advocate of self-sufficiency and a strong opposition to foreign aid or intervention, Sankara held the conviction that “he who feeds you, controls you”.

Sankara’s foreign policy was largely focused on anti-imperialism, with his government shunning all foreign aid. He insisted on debt reduction, nationalising all land and mineral wealth, and averting the power and influence of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank. His domestic policies were focused on preventing famine with agrarian self-sufficiency and land reform, prioritising education with a nationwide literacy campaign, and promoting public health by vaccinating 2,5 million children against meningitis, yellow fever and measles. As an ardent advocate of self-sufficiency and a strong opposition to foreign aid or intervention, Sankara held the conviction that “he who feeds you, controls you.” Sankara was vocal against the sustained neo-colonial penetration of Africa through Western trade and finance. He called for a united front of African nations to renounce their foreign debt and argued that the poor and exploited did not have an onus to repay money to the rich and exploiting. In a speech delivered by Sankara in October 1984, he declared, “I come here to bring you fraternal greetings from a country whose 7 million children, women and men refuse to die of hunger, ignorance and thirst any longer.”

Taking a similar stance to the revolutionaries Fidel Castro and Ernesto Che Guevara, Sankara voiced his displeasure over the arrogant treatment of the people of Burkina Faso by the rulers of the imperialist world. He vehemently criticised the impoverished conditions of the Burkinabe people and showed a strong determination to uphold the dignity of his people who had suffered savagely due to colonialism and neo-colonialism. Sankara had sworn to oppose the continued oppression of Africans and refused to subscribe to the economic bondage of class society and its unholy consequences.

To address prevailing land imbalances, Sankara embarked on a redistribution of land from the colonial ‘landlords’, returning it to the peasants. As a result, wheat production rose in three years from 1 700 kilogram per hectare to 3 800 kilogram per hectare, making the country self-sufficient in terms of food. He also campaigned against the importation of apples from France when Burkina Faso had tropical fruits that could not be sold. As a way to promote the growth of the local industry and national pride, Sankara impressed upon public servants to wear a traditional tunic, woven from Burkinabe cotton and sewn by Burkinabe craftsmen.

The modest nature of Sankara is one of the most prominent features of this African legend. He remained a humble leader who won the hearts and admiration of all his people and followers. He lived a relatively modest lifestyle, doing away with the luxuries widely associated with the oligarchs of Africa. As president, he had his salary cut to US$450 a month and reduced his possessions to a car, four bikes, three guitars, a fridge and a broken freezer. Sankara stood out from the leaders who led the freedom struggle for liberation in Africa. This was because he was a communist. He believed that “a world built on different economic and social foundations can be created not by technocrats, financial wizards or politicians, but by the masses of workers and peasants whose labour, joined with the riches of nature, is the source of all wealth”. A devoted Marxist, he drew inspiration for his fight for the emancipation of the working class from his belief that Marxism was not a set of “European ideals” that were alien to the class struggle in Africa.

The modest nature of Sankara is one of the most prominent features of this African legend. He remained a humble leader who won the hearts and admiration of all his people and followers. He lived a relatively modest lifestyle, doing away with the luxuries widely associated with the oligarchs of Africa. As president, he had his salary cut to US$450 a month and reduced his possessions to a car, four bikes, three guitars, a fridge and a broken freezer. Sankara stood out from the leaders who led the freedom struggle for liberation in Africa. This was because he was a communist. He believed that “a world built on different economic and social foundations can be created not by technocrats, financial wizards or politicians, but by the masses of workers and peasants whose labour, joined with the riches of nature, is the source of all wealth”. A devoted Marxist, he drew inspiration for his fight for the emancipation of the working class from his belief that Marxism was not a set of “European ideals” that were alien to the class struggle in Africa.

Sankara agreed with the words of Marcus Mosiah Garvey: “Education is the medium through which a people can prepare for their own civilisation and the advancement and glory of their own race.” Sankara recognised the importance of education in order to liberate his people from colonial damnation. He initiated a nation-wide literacy campaign, increasing the literacy rate from 13 percent in 1983 to 73 percent in 1987.

Sankara also understood the importance of women in the success of the revolution and the overall development of a nation. He empowered the women of Burkina Faso. As Pathfinder Press states, “From the very beginning, one of the hallmarks of the revolutionary course Sankara fought for was the mobilisation of women to fight for their emancipation.”

His commitment to women’s rights led him to outlaw female genital mutilation, forced marriages and polygamy, while appointing women to high governmental positions.

In October 1983, he declared in a speech that “the revolution and women’s liberation go together. We do not talk of women’s emancipation as an act of charity or out of a surge of human compassion. It is a basic necessity for the revolution to triumph. Women hold up the other half of the sky”. He appointed women to high governmental positions, encouraged them to work, recruited them into the military and granted pregnancy leave during education. His commitment to women’s rights led him to outlaw female genital mutilation, forced marriages and polygamy, while appointing women to high governmental positions.

Overthrow and death

On 15 October 1987, Thomas Sankara was murdered in a coup d’état, which was engineered by his trusted friend, brother and right-hand man in the revolution, Blaise Campaore. He was killed, along with 12 other officials, by his former colleague. Sankara’s body was dismembered and he was quickly buried in an unmarked grave, while his widow, Mariam, and their two children fled the nation. This was a disgraceful moment in the history of Burkina Faso. Campaore overturned most of Sankara’s policies and returned to the IMF. His dictatorship remained in power for 27 years until overthrown by popular protests in 2014.

General bankruptcy of leadership in Africa

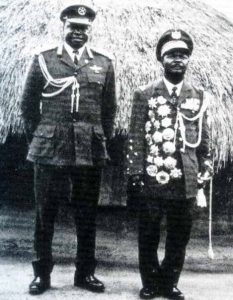

The record holders in butchering their own citizens. Idi Amin and Jean Beddel Bokassa of Central African Republic

Blaise Compraore who eliminated Capt Sankara but who has since been chased away from power by popular forces

At a time when Africans are desperately looking for development options and a way to regain an economically independent Africa, as envisaged by Sankara, Africa is bereft of such revolutionary-spirited leaders to spur on the fight for the economic emancipation and liberation of the continent. Much has been made of the discourse surrounding the potential re-colonisation of Africa by the emerging neo-colonial ‘kid on the block’—China.

October 14 marked the anniversary of the passing of another of Africa’s founding fathers of Pan Africanism, Julius Mwalimu Kambarage Nyerere. In moments such as these, African leaders must revisit the ideals of these selfless leaders, who wished for nothing but the total emancipation of the African continent. Just as Sankara professed a week before his dastardly murder, “While revolutionaries as individuals can be murdered, you cannot kill ideas.”

Poor governance is one of the factors that have plunged the continent into extreme levels of poverty and the far-reaching effects of low standards of living. Governance among Africans has been plagued with political and economic failures and this has seemingly provided proof of the incapability of Africans to rule themselves.

African governments are characterised by corruption, nepotism and political instability. Tsenay Serequerberhan (1998) posited that, “In fact, the 1970s and the 1980s have already been for Africa a period of ‘endemic famine’ orchestrated by the criminal incompetence and political subservience of African governments to European, North American and Soviet interests.” Corruption among leaders on the African continent has been a major setback to Africa’s attempt to realise successes in the globalised economy. This canker on the continent has blinded the leaders of Africa to appreciate the altruistic purpose for which they have been placed at the helm of affairs of the state. It is almost impossible to dissociate extreme poverty and wilful inequality from countries faced with sky-high levels of corruption. It is not an issue that affects governance only at the national level, but it also undermines collective African efforts at addressing common developmental challenges.

Corruption in Africa has helped to further concentrate income and wealth, which ought to be directed towards the development of her people, in the hands of the privileged few, to the detriment of many through the unequal and inequitable distribution of resources. Africa’s inability on the part of governments to deal effectively with poverty has been, to a large extent, due to corruption. Pan Africanism has lost its shine among African leaders, with African governments still under the shackles of neo-colonialism. The Organisation of African Unity (now the African Union) was meant to be a glowing reflection of the achievements of Pan Africanism, but is nothing but a laughing stock that cannot fund its own budget: An office complex to host its meetings had to be a ‘gift’ from China. On a day when we celebrate the revolutionary spirit of Thomas Sankara, it is imperative to realise that “African leaders have so much to learn from Sankara about humility and public service”, as was said by Samsk Le Jah, a musician. For Alex Duval Smith, “While Burkina Faso’s former leader may not be the poster boy of revolution, like Argentine-born Che Guevara, many taxis across West Africa have a round sticker of him in his beret on their windscreens”.