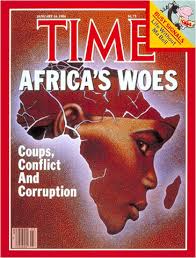

Kenya’s Nanjala Nyabola, Nigeria’s Chimamanda Adichie, Kenya’s James Michira and the best known of them all, Kenya’s Binyavanga Wainaina, have all struck global chords in protesting the controversy. That controversy is the ‘preponderance of negativity’ in the representation of Africans in the global media. It is a controversy with a long history and huge consequences for the humanity of the Africans. There are serious academic works in the vanguard of the protest but, at the level of popular culture, Wainaina’s satirical exposé “How to Write About Africa” remains the classic of this protestation. His 2006 article shows how Africans are ridiculed in the images of them favoured in global media portraits of their foods, wars, personhood and in the overpowering presence of darkness. The essence, for him, is an agenda in which “Africa is to be pitied, worshipped or dominated”. He tells chroniclers of Africa in the media: Your African characters may include naked warriors, loyal servants, diviners and seers, ancient wise men living in hermitic splendour. Or corrupt politicians, inept polygamous travel-guides, and prostitutes you have slept with”.

As such, any book dealing with any aspect of this controversy is bound to fly. Nobody within the Intervention network has read the oven hot text in full yet and this is, therefore, not a review of it but a critical celebration of its appearance at all. Its appearance at all is worth the attention because the claim of this book and the evidence for such claim would show the prospects of Africa reversing or never reversing its ordeal in History through the deployment of a unique kind of power in world politics. To trace that power, the story has to begin from the beginning.

As such, any book dealing with any aspect of this controversy is bound to fly. Nobody within the Intervention network has read the oven hot text in full yet and this is, therefore, not a review of it but a critical celebration of its appearance at all. Its appearance at all is worth the attention because the claim of this book and the evidence for such claim would show the prospects of Africa reversing or never reversing its ordeal in History through the deployment of a unique kind of power in world politics. To trace that power, the story has to begin from the beginning.

In 1904, Halford Mackinder, a man of many parts, including being an Oxford academic, delivered what he titled “The Geographical Pivot of History” where he asserted that the period thereafter was one in which the geography of exploration would be succeeded by the geography of philosophic synthesis of the world. Since any such synthesis of the world would be done from the eyes of the beholder, geography became what critics of Mackinder have called “a distinctive geographical gaze upon international politics”. Since then, the world has never been the same again because Mackinder turned geography into “an imperial vision of space”, a geo-cultural imagination that sought power through the essentialist construction and, by implication, control of that space. In other words, it is actually he who hinted very early that language does not just communicate, it also constitutes reality. That automatically made the media the most critical facility for geopolitical reasoning, the media being the hub of language use, especially now in the multi-modal age.

Prof Anthony Smith

But the world had to wait for Professor Edward Said to come up with a very radical demonstration of Mackinder’s thesis. Said did that in his 1977 essay titled “Orientalism” in which he deployed the concept of ‘Imaginative Geographies’ to explain the connection between the media, geopolitics and conflict in the contemporary global order. He locates that connection in how those who process media texts in the global centres of power operate from a ‘we here’ versus ‘they there’ frame of reference which turns difference into oppositional elements. And this explains the disciplinary moves observable in the hegemonic instinct in reporting Others in the global media. Global media here is understood to embrace other platforms of popular culture such as arts, the internet, film, cartoons and video games. Three years after this extraordinary essay, Professor Anthony Smith, another Oxford scholar but an Historian added value to both Mackinder and Said’s argument in his 1980 book titled Geopolitics of Information: How Western Culture Dominates the World.

What all the above background amount to is that there is truth in the claim of ‘preponderance of negativity’ against Africans in the global media but it is not an aimless project or a problem of journalistic recklessness but a reality which can be explained by the theory and practice of imaginative geographies. But that is just one dimension of the problem. In the age of internet and multi-modality, isn’t Africa going to realise the power of discourse and use that form of power to get itself out of victimhood?

This is where Wasserman’s book could become strategic in terms of showing how successful or otherwise South Africa might have been in trying to do so, especially since it miraculously became a member of the BRICS geopolitical block, very much against almost all of Jim O’Neil’s criteria for membership of that club. If South Africa has been a success story by which ever criteria, it means other African countries can utilise the practices. If it has not been an easy victory for South Africa, other African countries can learn from its story. An earlier but similar attempt in relation to Nigeria did not turn out very successful because the book project, according to post publication editors, took too many subject matters in one book. It is now in the editorial slaughter slab to make it a book on a single story. But, even then, it is clear Nigeria has not got on to an instrumentalist sense of the media in geopolitics although Nigerian leaders, like Thabo Mbeki of South Africa, believe that Africa has lost ownership of the African story because the continent hasn’t got the media infrastructure to project continental narratives of self. Rather, it is a continent relying on the radical and cosmopolitan goodwill of Western journalists in revolt against global injustice.

This is where Wasserman’s book could become strategic in terms of showing how successful or otherwise South Africa might have been in trying to do so, especially since it miraculously became a member of the BRICS geopolitical block, very much against almost all of Jim O’Neil’s criteria for membership of that club. If South Africa has been a success story by which ever criteria, it means other African countries can utilise the practices. If it has not been an easy victory for South Africa, other African countries can learn from its story. An earlier but similar attempt in relation to Nigeria did not turn out very successful because the book project, according to post publication editors, took too many subject matters in one book. It is now in the editorial slaughter slab to make it a book on a single story. But, even then, it is clear Nigeria has not got on to an instrumentalist sense of the media in geopolitics although Nigerian leaders, like Thabo Mbeki of South Africa, believe that Africa has lost ownership of the African story because the continent hasn’t got the media infrastructure to project continental narratives of self. Rather, it is a continent relying on the radical and cosmopolitan goodwill of Western journalists in revolt against global injustice.

However it goes, things might never be the same again. For one, this book is bound to foreground epistemic curiosity among regulatory agencies of African universities, parents, heads of universities, government officials, students and academics as the book circulates over time with particular reference to the study of Critical Geopolitics or Discourse Theory on the continent. At the moment, these domains are hardly prominent in the course listing in Mass Communication, Literature, International Relations, Geography, Discursive Psychology, Peace and Conflict Studies, Political Science, Political Economy, Diplomacy and War Studies. Certainly, that is the case across Nigerian universities. Much of the academia in these disciplines in many African countries, particularly Nigeria, is still done from rationalist, Behaviouralist methodology. That’s great but new developments in knowledge must be incorporated if those who are passing through these universities are to be able to compete. There is every need for students reading Mass Communications, for instance, to stop thinking of the media as an institution functioning in terms of information, education and entertainment to a more critical view of such simplistic rendition. Or, those reading Geography to be parroting the ancient definition of Geopolitics as the impact of geography on international politics! If such a definition still makes sense, then how might we explain the topological process that underpins Drone Warfare, for example? And so on and so forth!

Prof Wasserman

Wasserman, a professor of Media Studies at the University of Cape Town in South Africa has obviously written a major work in a realm which has seen many publications of late. One of such publications is Africa’s Image in the 21st Century edited by Mel Bunce, Suzanne Franks and Chris Paterson, the first two of whom are communication scholars at the City University in London while Paterson is at the University of Leeds in the UK. Theirs was 2017 and it is considered a full meal as far as the controversy in question is concerned. The difference between all such works and Wasserman’s is while previous works were concerned with deconstructing the global media, Wasserman is about Africa writing the global space. It is an intellectual ‘about-turn’, to borrow a lexicon from our military brothers and sisters.

Wasserman, a professor of Media Studies at the University of Cape Town in South Africa has obviously written a major work in a realm which has seen many publications of late. One of such publications is Africa’s Image in the 21st Century edited by Mel Bunce, Suzanne Franks and Chris Paterson, the first two of whom are communication scholars at the City University in London while Paterson is at the University of Leeds in the UK. Theirs was 2017 and it is considered a full meal as far as the controversy in question is concerned. The difference between all such works and Wasserman’s is while previous works were concerned with deconstructing the global media, Wasserman is about Africa writing the global space. It is an intellectual ‘about-turn’, to borrow a lexicon from our military brothers and sisters.