By Adagbo Onoja

This is a 2006 interview conducted and reported in The Nation where this reporter was the Managing Editor. It is reproduced here over a decade after because it is time someone brings the relationship between the economy and the confusion overwhelming Nigeria today before the country is consumed by social media level of analysis. Dr. Peter Ozo-Eson was the Director of Research and Chief Economist of the Nigeria Labour Congress, (NLC), at the time the interview was conducted. The University of Ibadan and Carleton University, Ottawa trained economist as well as former academic at UNIJOS says deregulation is not the way to transform the Nigerian economy. He lets us into the mind of Nigerian leaders, principally former president, Olusegun Obasanjo whom he says swings between neoliberalism and nationalism in terms of managing the economy.

What would you say is the state of the Nigerian economy today?

Ozo-Eson: I would say it is an economy that is growing but it is a growth that is not creating jobs. It is, therefore, a growth whose benefits are concentrated within a tiny fraction of the population. Therefore, poverty continues to be a major issue as well as unemployment. The ordinary Nigerians are unable to accept that the economy is doing well because the growth does not touch them.

Do you think deregulation is a good attempt at addressing this?

Ozo-Eson: What deregulation seeks to do is to transfer downstream sector into corporate/private sector hands as a response to problems of inefficiency and bottlenecks in supply. But as long as export of crude oil is the source of income, only a tiny segment of the population will benefit. So, deregulation will not change things. A conscious, deliberate investment pattern in using money from oil to create a broad based labour intensive techniques in agriculture, manufacturing and thereby engage people would have been better. But policy today says government shouldn’t get into investment. Rather, they are talking of promoting private sector in the productive area. In the medium and long term, that may create a productive base in agriculture and industries but in the short term, that transformation is not likely. A government that plays the role of direct job creation by investment in the productive areas in agriculture, manufacturing, construction in order to redress the imbalance in access is what one would have expected.

What is the comparative experience of African development strategies?

Ozo-Eson: We need to be careful in the comparison. It is the oil earnings that created what we are talking about because it brings in a lot of resources but which is concentrated in the state. In many other African countries, this is not the case, their own choice is not driven by growth that is not creating employment or eradicating poverty.

The good comparison with Nigeria would be Libya, Angola and Gabon because they all have oil. Libya is interesting because it took a different route from deregulation. The government of Libya went directly to create infrastructural base that has improved quality of life of the citizens. The average Libyan family, to take an example, has a right to ownership of accommodation. Government invested massively in housing, by doing it directly, not leaving it to market forces. It transformed desert land into green lands for farming, what they call man made lakes. Although Libya could be said to have an advantage in its much smaller population, we in Nigeria cannot use that argument or blame our underdevelopment on that because if properly directed, our population can produce a development wonder. Our crisis is the crisis of official policy.

The second example is one that has no oil and that is Botswana. But it has raw materials in Diamond. But they succeeded in creating a manufacturing base because they insulated earnings from the raw materials and set long term development plan in which they isolated only three to devote the resources. These were creating a manufacturing infrastructure or productive base through injection of capital; the development of human capital through education, health and so on and lastly, investment to mediate inter-generational equity. This last item is very interesting because it means they were planning for generations unborn yet. The result of these three areas of focus is that they have been able to create a dynamic sector which has also led to rise in poverty reduction and good economic performance, characterized by relatively low unemployment.

The lesson in all these is that development requires the state to position itself. The developmental state cannot sit back and say that the private sector will, in itself, engineer development especially in a country at a very low level of development like ours. There is a point you attain in development that you can do that but in history of economic development, the private sector led economy comes about only after a mature economy has been created. In the West, it became the case after they had used the developmental state and direct intervention to reach a level of development. Can you imagine the underground train in London at the time it was built if it was the private sector economy? Yet we are at the same stage in Nigeria now when private sector or the profit motif would not create the type of complexes that would be the basis of development. In particular, the type of manufacturing that will place Nigeria on competitive global map is not a job for the private sector because our private sector is also constrained by our stage of development. If you want to accelerate development, it is a partnership you must forge.

How would such a partnership operate?

Ozo-Eson: A short term view may be best for the private sector. That accounts for the under-development of the railway in Nigeria. Instead of the railway and its heavy gestation period, these business men are competing buying small buses which is a high paying and immediate return kind of business. The areas such as railway can be graduated, leaving the government with providing the minimum investment. The chances of attracting private investors would be greater this way. Anyway, I take the view that at this stage of our development, government cannot afford not to be an active participant in the productive sector. Although this has to be done carefully as the private sector is saying that the historical record of public enterprises is that of non-performance, corruption, political interference, patronage and all that. I would say that if it is the way we operate that is the problem, then the reform should be about changing the way we operate. In any case, there are other countries where state owned companies have done well. The South African energy company is wholly state owned. They are now even branching out. There are other examples as in the case of Brazil. So, the challenge of true reform should be how we too can run public enterprises well. Then we would have opportunity to channel resources from oil to productive sector especially agriculture and manufacturing. Because that is the only way to produce growth with jobs!

Why is this not the option of the leaders in Nigeria?

Ozo-Eson: Earlier philosophy of development in Nigeria actually had this type of vision. Its strongest manifestation is the provision in the Constitution that the state shall control the commanding heights of the economy. That provision is a fall-out of Nigeria’s history of economic philosophy. Even in breaking and succumbing to globalization, we have not been able to expunge that philosophy. So, we operate a dissonance between that vision and the NEEDS. These two are completely contradictory.

But to directly answer your question, the issue is the global environment we operate now. There is a feeling of victory in the neo-liberal quarters, symbolized by the IMF and the World Bank. Since our governments take dictations from these international financial institutions, it does not require a careful reading between the lines to know where these ideas have been incubated and are dictated to us. So, the problem is the inability to resist.

Why are they unable to resist. Their counterpart in Malaysia, for example, resisted the World Bank and today, they are the better for it.

Ozo-Eson: Nowadays, we all shy away from analyzing issues in terms of class character. We said earlier that a tiny minority benefits from what is going on. As long as the neo-liberal policy benefits this minority, they have no qualms. The ruling class is part of those benefiting class so they have no problem implementing them. They may rationalize their acceptance to implement these policies but we know it is because it is beneficial to them. So, there is no conflict. Rather, it helps them to consolidate their hold on power as they get support from their patrons and masters in the international community. The type of growth these policies promote is beneficial to them.

Unlike 2012 when Christians would be guarding Muslims at prayer, the country is now so divided that a nationalist backlash is doubtful, especially as President Buhari and former president, Obasanjo are set to slug it out among the same populace.

Do you see any possibility of a nationalist backlash in Nigeria?

Ozo-Eson: I hope that there is because I am convinced that majority of Nigerians identify with Chapter Two of the Nigerian Constitution. So, I hope this majority will be able to organize, have a minimum programme and reposition to lead the nationalist fervor to control power and reverse these neo-liberal policies. As of today, that group is not organized. But as things get worse, they may be able to re-group and assert themselves. Things we may regard today as dead may just be stagnant. Even in the international arena, the ideology of end of history is being reversed even through electoral defeat, especially in the former Soviet republics.

That has not been the case in Africa. What is our case likely to be?

Ozo-Eson: What is likely to be the case, at least in the short run, is that the results of the continuing crisis of poverty and mass unemployment will worsen the situation. GDP figures will be showing growth and regime publicists will be bandying these about in the newspapers but poverty and exclusion will be growing. And disenchantment too! This will heighten the contradiction, followed by fiercer contestations. Already, the signals are here. Look at the volume of criminality and agitations. These are responses to the crisis of unbalanced growth.

These responses are not coming in any organized form yet.

Ozo-Eson: Yes, they are not organized. It is the crisis that will organize them in a way. Organized responses normally correspond with the level of decay and we are reaching that point.

Are you not afraid that the perception of the crisis could assume ethno-religious and regional forms and instead of a nationalist struggle, the nation breaks, even before the crisis managers know what is happening. Because poverty has been at the base of all recent break-ups of nations!

Ozo-Eson: It could lead to a breakdown or a vacuum which some forces have to fill. It is a challenge to leadership and many other segments of the society that this does not happen. This is why it is important to have nationalist leadership that is sensitive enough to such possibilities by not aggravating poverty and, therefore, tempting people to look for explanations for their conditions in forces of anarchy.

When you meet Nigerian leaders, the ministers, the legislators and so on, what aggregate feeling do you come away with?

Ozo-Eson: I get the feeling from many of them that they believe the route to development that we are taking now, this neo-liberal ideology, is the correct one. You can see that in many of them. Those ones acknowledge that there will be pains in the short run but that we are on the way to success. The question I ask them is how do you manage these pains in the short term? They are unable to answer that. Their vision of the world is one driven by the conviction that free market is the ultimate route that will deliver the country. Some of them believe in that with some passion.

But I have also met people in government who in public defend this free market ideology but disagree with it violently in private. I have no problem conducting a debate with those who are convinced the market road is the answer. But I have problem with those who are not convinced but pretend to support it. I would not want to mention names.

On which side do you locate OBJ in this spectrum?

Ozo-Eson: We know that when the neo-liberal invasion started, OBJ was one of those who came out publicly to say that we must do it with human face. That shows to me that deep down within him, that was what he believed to be the best. Periodically you see where the nationalist sensibility in him comes to the fore. And such occasional protests even if temporarily signify that no matter the pressures, he knows that neo-liberalism is hopeless for a country in Nigeria’s stage of development. Even recently, you see him trying to resist. Contrary to the pension model they were given which says you should give pensioners instruments to hold, they are now paying cash because I believe he knows giving the kind of people who are pensioners here instruments to hold is nonsensical. So, I see him as somebody who is operating under pressure from the international policy mill, (the World Bank, the Washington Consensus, etc). Although he has submitted to them for reason of regime survival, he is still unable to fully suppress the nationalist tendencies he has always possessed. Hence his periodic swing between neo-liberalism and nationalism.

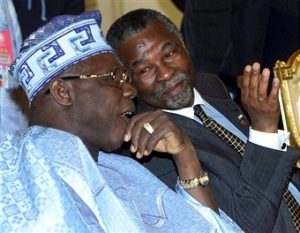

Obasanjo and Thabo Mbeki, former preident of South Africa: two of a kind in swinging between neoliberalism and nationalism or better still, economically neoliberal but culturally nationalistic

In which case, he might actually be a very unhappy man

Ozo-Eson: For a person to publicly come out in defence of what he thought was right, take a position in favour of SAP with a human face like he did and the same person to be compelled to reverse himself, something must be going on in his mind. Whether that is unhappiness, I can’t say.

The henchmen of his reform, are they then his boss or he is still theirs?

Ozo-Eson: Those ones derive their powers from their role of pushing the views of the global system and to the extent that they push that line, they are listened to. The power of that system is their own power but OBJ is his own man in the sense that they cannot do anything if he does not agree. So, they have to get him to agree, which they have done.

How is it possible for someone to be groomed that he or she has no problem pushing these position?

Ozo-Eson: It does not require so much grooming. Some people’s socialization has prepared them for that role. There are some people whose socialization has prepared them as intellectual vanguards of the privileged class. The type of policies that will promote the interests of that class comes naturally to them. Now, some of them who have not evolved that way may catch on it opportunistically to be part of the vogue.

In other climes, the nationalist elements in the bureaucracy, labour, media, political parties and the intelligence will thwart such overbearing elements marketing foreign interests. Why does this not seem to be the case here?

Ozo-Eson: In other countries, the intelligence will warn you about the implications. I hear that our own security provides that too. As for labour, media, they have been fighting too. It may just be that nationalist elements in Nigeria suffer from a unique absence of coherence. This can be seen from the case of labour. When it is out there, the rest of the actors such as you mentioned think it is labour’s show. This tendency to see mass protest as some entertainment is all part of it.

We started this interview with what you think is the state of the Nigerian economy. We will end with the same question about labour.

Ozo-Eson: The implementation of these neo-liberal policies have impacted on labour itself. When there is mass unemployment, labour is automatically in trouble. The capacity to resist is further weakened. Within labour itself, there is the same weakening of nationalist spirit. The discourse that was ideological has also weakened. The same kind of neo-liberalism is informing labour, both within labour itself and among labour leadership. So, the challenges of the neo-liberal ideology for the economy are the same for labour itself in terms of the one-size-fits-all mentality. But there should be encouragement of discourse. We can’t accept that only one view of reality is the correct one.