This page has been updated to embody part 1 and 2 of the two part piece on General Theophilus Yakubu Danjuma unlike before when it was published in two separate parts and the second part was hacked off Intervention by an intruder. Here, the two are now integrated. for the records – Editor:

By Adagbo ONOJA

Before the end of the Cold War, ‘Third World’ militaries were generally regarded as conveyor belts of anti-communist politics. This assumption was said to manifest in how they acted as implementers of liberal modernisation strategy for which Western scholars tipped them as the most rationally organised to accomplish in non-Western societies. Of course, the argument has since changed with the end of the Cold War. The West is no longer in the mood for military rule in ‘Third World’ countries but before that shift, the Nigerian military, for instance, found itself implementing Structural Adjustment Programme, (SAP) which is an updated version of modernisation strategy. The conveyor belt claim in relation to the Nigerian military is, however, a bit more complicated. This is because it is the same military which introduced the SAP that also implemented or supervised the implementation of the Second National Development Plan which is the most elaborate articulation of state interventionism in the history of Nigeria so far.

The puzzle in all these as far as the subject matter here is concerned is how one of the unforgettable heads of this rather complex military has never been heard arguing for SAP or liberal modernisation package. That is to say that unless someone comes up weaving evidence to the contrary, some of us have not found TY Danjuma adding his voice to the chorus about there being no alternative to SAP or to reform. The argument here is that any ‘Third World’ soldier who has refrained from that entanglement is an enigma in the deepest sense of that word. And such a soldier deserves to be studied beyond hagiography, the dictionary meaning of which is ‘biography of a Saint’ or ‘biography which treats its subject with undue reverence’. Instead of such a biography, it is rather a thoroughly critical cracking of this puzzling personality that is called for simply because History is constitutive in its own way. Perhaps, it is apt to mention that critical does not mean criticising but inserting the subject matter in its deeper social contexts.

The puzzle in all these as far as the subject matter here is concerned is how one of the unforgettable heads of this rather complex military has never been heard arguing for SAP or liberal modernisation package. That is to say that unless someone comes up weaving evidence to the contrary, some of us have not found TY Danjuma adding his voice to the chorus about there being no alternative to SAP or to reform. The argument here is that any ‘Third World’ soldier who has refrained from that entanglement is an enigma in the deepest sense of that word. And such a soldier deserves to be studied beyond hagiography, the dictionary meaning of which is ‘biography of a Saint’ or ‘biography which treats its subject with undue reverence’. Instead of such a biography, it is rather a thoroughly critical cracking of this puzzling personality that is called for simply because History is constitutive in its own way. Perhaps, it is apt to mention that critical does not mean criticising but inserting the subject matter in its deeper social contexts.

The notion of a thoroughly critical work on a TY Danjuma automatically implies the craftsmanship of a critical theorist rather than just anybody either because s/he bears a high academic designation or teaches in a university or is one of the intellectual commanders around TY. No. That’s not the point. If this is a special project for the larger Nigerian society and for the future, then someone capable of maintaining a critical distance between him or herself and the TY phenomenon is required. Objectivity is a dead horse, hence the reference to critical distance.

The point is that even if it is discovered that TY has been advocating for neoliberalism, (which is not impossible), there are still a number of standalone instances of exceptionalism in and of him that should interest Nigeria. Here is someone, for example, whose sense of capitalism is worth investigating. So far, he does not appear to be a typical one. A capitalist who does not know what to do with just $500m is not a typical one. That is the unspent half of the $1b he made from selling his oil block. Most capitalists would start looking for another $500m and another and another. It is that insatiable greed that makes critics call them a band of hostile brothers or some expression to that effect. It is that greed for more and more ‘profit’ that brings about all wars. So, a ‘capitalist’ with limited appetite for ‘profit’ is an automatic subject matter for critical sociological study because such an attitude suggests a capitalist with humanity in him. But, where might that humanity be coming from? From cultural upbringing or from his religious rearing or from military induction or some yet unknown variant of idealism?

These are important questions especially when linked to his sense of what to convert his own share of the benefits of the nation’s oil industry to. He found that in a good cause institutionally administered independent and outside of himself by establishing a Foundation. Doing so at a time he was no longer in expectation of any political fortune gives that a mystique that is, again, uncommon. The assumption is that there is in place a bureaucracy that ties the TY Foundation to remaining faithful to its ideals as the founder naturally winds down with age in terms of time for attention to from nitty-gritty, supervision, reading through scripts, identifying, recognising and remembering much. The demise of the Center for Advanced Social Sciences, (CASS) in the aftermath of the demise of Prof Claude Ake makes this an important point to make at this point in time.

What about him as someone who could have been Head of State but declined at every turn? It is generally understood he could have had it if he wanted it in 1976 and in 2007. So, why did he not take it? By what constitution might he have been acting? An idealism strange to the general standard of reasoning in the Nigerian political space or an uncommon understanding of that space that discourages thoughtful elements?

Could TY have missed his way into the military profession? This is a question worth posing in the light of the manner he has improved himself intellectually at a time the military was very much anti-intellectual in contrast to today when the average military officer has gone places academically. He does manifest the mind of a strategist and the mind of a scholar even if this claim is based just on a close reading of his February 2008 interview in The Guardian and even in Lindsay Barret’s Danjuma: The Making of a General.

He remembers when he was a soldier!

It might look arrogant or immodest to think that one knows better who can write this work. But the standard of work expected in this ‘biography’ would have been the sort of work that the out-gone generation of Nigerian scholars would have best handled as in the case of General Gowon by Professor Isawa Elaigwu, warts and all for the obvious reason of their proximity. After Elaigwu, Bolaji Akinyemi would have been the best. Akinyemi is not a critical theorist but there is an inspiring conservativism in Akinyemi that gives him an edge. In the absence of Akinyemi, there are a few sufficiently ‘crazy’ crackers around. There is one at the University of Ibadan. There is another one in Bayero University, Kano and there is one in ABU, Zaria. The question is whether these are the sort the intellectual commanders around TY would be able to work with, whoever they might be now. But it is beyond the wishes of gate keepers because all gate keepers define loyalty in a manner that make them guilty of the Hausa saying that the problem is not the king but the king’s gate keepers. But the issue is that this is a task beyond the sentimental attachment of any band of hero minders. There is no disconnecting TY from his religion but this is not about his religion yet even as crucial a component of it as it is. There can be no decoupling of TY from his region. That is also a crucial component but this sort of work goes beyond that. There cannot be a successful separation of TY from the military profession because that is definitive of him. Yet, this is not a story of his military career. This is about TY in all his complexity.

It would be shocking if this sort of work is not already on-going. Great if that is the case and greater if it is in the hands of somebody who has the preparation to handle it. Of course, no one work will close the TY phenomenon but every work is underpinned by time and space. That is what is meant when we talk of someone who can handle it. TY himself has talked of an autobiography that would be explosive. That would be welcome but it might be apt to say that such would only be an important raw material for the work being contemplated. In other words, this is the sort of work we expect to see on the reading lists of university courses in civil-military relations, political sociology, strategy, Nigerian foreign policy, agent-structure nexus, the military and the state, state and economy in Nigeria, etc, etc, not a shallow, disjointed story that everyone forgets about as soon as the launching or public presentation is over, no matter the publicity blitz.

May God make preserve all of us to live to see this sort of work, attend its public presentation while TY is still alive! The second and concluding installment of this series would look at TY in relation to leadership and the one, last thing that needs the TY dosage in Nigeria before anything happens.

ONOJA is a member of The Editorial Collective of Intervention Online

TY Danjuma @ 80 (2): In the Aftermath and the Last Duty

By Adagbo ONOJA

In spite of the miserable character of the development of capitalism in Africa, the continent is not immune to the fragmentation rupturing industrial societies. It is the multifarious character of contemporary societies (ethnic, national, sexual, environmental, etc) that pushed post-Marxists to claim that the Marxist imaginary of reality as outcome of the tussle of two dominant classes has been questioned. While the last word is yet to be heard on the debate on that claim, the same miserable development of capitalism has so shaped the struggle for access to the very lean national economy in the typical African country around exclusionary offensive and defensive strategies. One such instrument in the case of Nigeria is the six geo-cultural units by which the country works, along with other dominant cleavages such as the North-South dichotomy or the Christian-Muslim divide. It is still a waiting game for the leadership that would come along with a theory and practice of nationhood that would push these cleavages to the backside and centralise more progressive narratives and practices thereto, building on the great deal of integration that has taken place already.

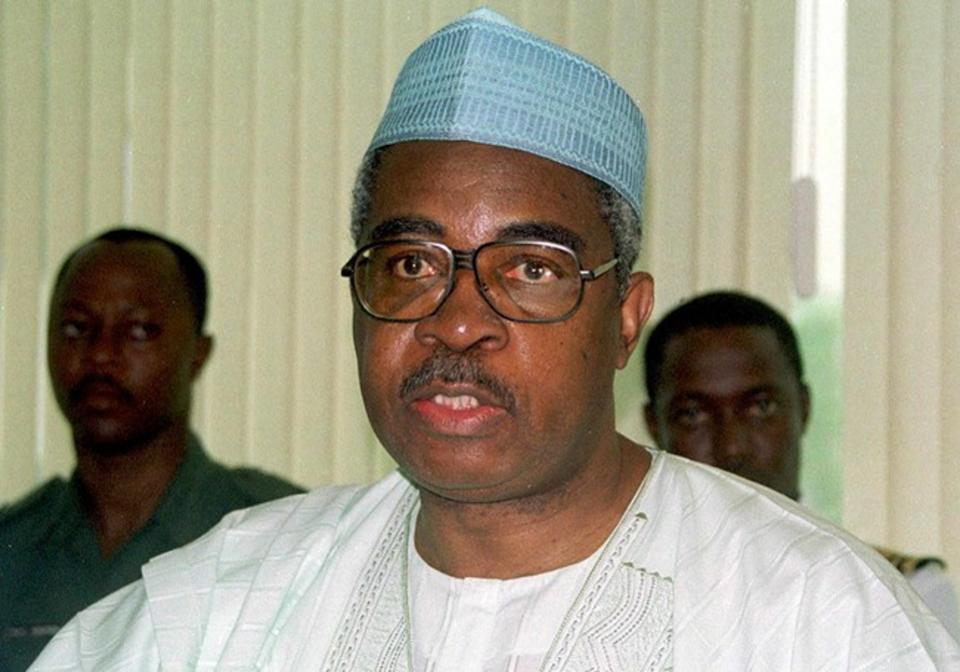

Gen Danjuma arriving Makurdi, the Benue State capital a year or so ago

Until that happens, it would even be wicked to expect the Middle Belt (or its less problematic name of Central Nigeria) not to claim a TY Danjuma in a polity in which the region is co-existing with beneficiaries of the legacy of power scripts by the Ahmadu Bellos, Awolowos and Ziks (in that alphabetical order). It may not be fair to talk of Theophilus Yakubu Danjuma, aka TY in the rather restrictive sense of the Middle-Belt, given his massive penetration of the Nigerian national space and beyond. But in a highly fragmented world driven by the politics of fear, claiming TY Danjuma by or for the Middle- Belt is permissible ‘chauvinism’. For, this is a region that has been going under from the paralysing effect of its self-understanding as a victim of organised physical and structural violence. A collective Post Trauma Stress Disorder can even be claimed for the region in its open wailing, lamentation, anger and frustration. That is to say that a totally self-negating or disempowering narrative of its fortunes and misfortune is on display.

In that narrative of victimhood might the problem lie, substantially. Yes, the Middle-Belt has been a theatre of all manner of largely organised violence but it is still a question of what anarchy might mean. It is not the tree that fell in the woodland that is real but what significance is attached to the crashing of the tree. If nobody talks about it, the fall may be real but in what sense? Hence the logic of anarchy being what we make of it. A narrative of victimhood is a narrative of unintended acknowledgment and celebration of the heroism of one’s traducer(s). That is how representational practice works. Is it not a curious thing, for instance, that an Aminu Tambuwal or a Nasir el-Rufai will be subject of national speculation for the presidency but not a Darius Ishyaku, their Taraba State counterpart, an intellectual, an architect – one of the most creative disciplines, a former minister and a politician? It cannot but simply be that, overwhelmed by victimhood to the neglect of the politics of representation, the Middle-Belt is missing in action. That is not yet part of their arsenal in the struggle for power within the dynamics of ruling class politics.

The implication is that the region is in dire need of the TYs in it, as a shield against perceived enemy forces and interests. A TY who compels anyone relating to the region to think of a TY factor before making his or her move in that relationship! It is such that, although only very few members of the Middle Belt elite do circulate within the TY orbit, there is, nevertheless, a TY symbolism working for the region. That is how the world actually works, more so for a region whose other ‘natural’ godfathers have died off and have not been reproduced. Dr Joseph Tarka has been gone since. Dr. Abubakar Olusola Saraki and Chief Solomon Lar replaced him but they too have gone. That has left only TY who is there not because he has consciously sought it but has been constituted as such by a combination of roles he has found himself playing in contemporary history of Nigeria.

Otherwise, he was the most unlikely success story in godfather politics, being a blunt talker rather than a negotiator. And being, fundamentally, a retired military officer whom, no matter how much mellowing might have occurred in his life, remains military in orientation. What Professor Isawa Elaigwu said about Obasanjo as suffering from residual militarism is applicable to the entirety of that tribe. By late Stanley Macebuh’s reckoning, only General Ibrahim Babangida, (IBB) has successfully transformed into a civilian. By storming the civil society from cultural to philanthropic to religious to the educational to peace practice and to multiculturalism, TY would have out-scored IBB by now if Macebuh were re-doing his piece.

There is no way Nigeria’s Middle Belt would not cluster around such a giant for a godfather, not minding how scary the concept of godfather is in Nigerian politics. That is a godfather in the sense of someone whose trajectory in Nigerian politics acts as a multicultural binder, giving him the stature to ‘negotiate’ on behalf of the region where it matters. This is what all past leaders of the Middle- Belt have done by constructing resistance to hegemony in ideological, principled politics. That is the only way Joseph Tarka would have brought Ibrahim Imam from Borno State of today, create a constituency for him in Tivland and enable him to appear in the northern legislature to everyone’s chagrin. Olusola Saraki followed the same multiculturalist pathway and we see that in how the Northern Union he created is the platform centralising him today through memorial lectures and so on. Solomon Lar too followed the ideological and multicultural trajectory, holding the record of applying the concept of ‘Emancipation’ twelve full years before the concept emerged with determination to push out class analysis. By the way, do we have any case where a Middle-Belt political leader has implored any researcher to undertake a doctoral level study of Lar’s Emancipation agenda, from the doctrine to the practices and the outcomes – the positive and negative ones vis-a-vis the issue of gap(s)?

The late Chief Solomon Lar

In summary, all three had principled resistance to hegemonic forces, be it colonial, class or party. So, common to the three in one way or the other is a construction of the Middle Belt as anti-thesis of hegemony, even as the problems of inter-group relations in Northern Nigeria that they encountered were no less painful than what they are today. They must have correctly read the region as so impossibly constituted to be read in ethnic, religious or geographical because the reality of external enemies does not annul sites of local fascism, exclusion and structural violence that dot the Middle-Belt landscape. The interesting thing about TY Danjuma is how, though not a career politician, he has followed the pathways of his ‘predecessors in the office’ of the godfather. That is the non-ethnic, non-religious or multiculturalist sense of the Middle-Belt in relation to otherness. We see that in his investiture with the traditional title of Jarmai in Zaria Emirate, his deep roots in the Southsouth, the same as in Southwest where he has lived much of his life and, of course, godfather stature for the Middle-Belt. One could talk of understandable residual sentiments against him in one or two places but how thick is such? So, TY has followed the script of his predecessors.

But at 80, TY would be winding down, reducing his social and other engagements. That makes the question of a successor an urgent agenda before subterfuge enters it. We can talk of a successor even as the office does not exist as such. But the question of a successor automatically raises the question of why the region seems to be in deficit of new Tarkas, new Sarakis and new Solomon Lars. Where are the new versions of the legends for a region identified with unifying leadership for Nigeria, given its contributions to military service and to governance but which has been absent or in decline since 1999? Who are those individuals who should have been the region’s equivalent of the Bola Ahmed Tinubus, for example, as far as godfather is concerned? How did Tinubu build up his clout in his time but not the ones now?

Senator David Mark would certainly be one of those in contention. He has been in power in the ‘real’ sense of it for the past twenty years. He has successfully acquired a national mystique. While there is no doubt about that, it has remained a contested mystique when, at every election, he has been challenged at home and his victory has always come from the court. Harsher critics look for the institutions and individuals he has built. The claim is that the result is not inviting. Professor Jerry Gana is the other person. Attaining the professorial rank before ever entering politics makes him a permanent model of the Middle-Belt imaginary. That is in addition to his sensational entry into politics with the defeat of an establishment candidate in 1983. To his credit too is a vast and unusual experience in academia/research, social mobilisation, radical politics, party building, governance and development practice. Equally unique about him is the ability to remain relevant to a long succession of regimes. But, like Mark, his critics look for the individuals and institutions he has built and they say they can’t find them beyond a nuclear network.

Dr Abdullahi Adamu is another name, a politician from earlier tradition of politics. The story is not too different. His own case is complicated by the non existence of any narrative around him. It is such that there is nothing to agree with or dispute about him. But, as an older politician, there must be certain capabilities he must have vis-a-vis the region.

There is Senator George Akume who retains his rating as a powerful political figure. He did send a developmental signal by adding value to the Benue State University in the ultra-modern Medical School his regime built there. It is to his credit that Benue State University Teaching Hospital is rated outstanding today. But Senator Akume doesn’t pose the Middle Belt claims on Nigeria in his politics. It is possible he does his things quietly. But quietism in politics in the digital age is a dead track. Donald Trump is not a fool in finding solace in the tweeter. As someone said recently, there is a logic to it that critics of that media tactic have not taken into consideration.

Chief Audu Ogbeh is well regarded, a powerfully rhetorical and an experienced politician. He is one of the few plausible successor godfather candidates by acclamation today. What would anybody be looking for that he hasn’t got? Privileged formal education, patriotism, political positions that were strategic, experience of Second Republic politics, literary exploits and what have you. He stands an enhanced successor godfather should the rice-growing revolution he is said to be engineering turns out a sustainable development praxis. Even then, critics would still ask of the individuals and the institutions the chief has built up. Or are those things there?

Chief Stephen Lawani, his kinsman, is not fundamentally different although, unlike Ogbeh, that one is on the quiet side and a rather co-operative rather than a turbulent political personality. Remaining scandal free even after so many years in the turbulent world of business and politics makes him a regional leadership asset especially these days when a corruption free certification is becoming such a decisive variable. Conceptually sensitive and culturally well linked across Nigeria, Lawani is, however, in need of rethinking his approach to politics from being a strategic doer to a populist approach to empowerment. The approach of strategic doing has denied him the benefit of his practice of helping others unlike in Europe and North America where it would have given him considerable mileage. Coming from Idomaland where a peculiarly republican virus forbids the practice of taking communal shopping list to successful sons and daughters but given that all greatness comes from ‘home’, there is a re-learning imperative for him.

Leaving something behind for others institutionally but there is still a challenge beyond this institution: building future thinkers

We can go on and on with this listing because there are many others, including dark horses or young Turks. But, as things are today, a non-traditional politician similar to TY, (a military man) could equally ‘succeed’ TY if care is not taken. In other words, a same combination of factors that positioned TY Danjuma as Middle-Belt leader in spite of himself and in spite of his professional rearing could throw up some priest or another soldier into a position which had been held predominantly by career politicians. Whether a priest or another soldier emerges as TY’s successor, the TY story requires a pan-Nigerian last paragraph. That goes on like this: It is great TY Danjuma has put up a Foundation that is touching lives. It would be even greater if he could extract from the Foundation a commitment to build an intellectual incubation centre that can produce critical thinkers. More than 75% of the African crisis is the crisis of imprisoned minds. The Middle-Belt, Nigerian and African crisis are similar to what we were told about whom to marry as youngsters. The emphasis was on the intelligent wife because the intelligent wife, by the hamlet logic, could kill the husband but raise him up quickly before he is thrown into the grave. This is contrasted to the foolish but love or loyalty proclaiming wife whose foolishness is what would kill the husband without her knowing she is the culprit.

In this story, the intelligent wife is a critique of mediocrity and sycophancy. As things are today, the future is frightening because thinking and self-correcting or reflective leadership, similar to an intelligent wife, is lacking. They have to be produced through incubation. It could be by university, something like a place for gifted children. But it could also be a training centre that fries those who experience it in terms of critical thinking. After all, what does Oxford do? Or Cambridge, Harvard, Sorbonne, just to mention a few. It is not any magic. They produce people who are leaders because they are the thinkers who frame the problems. That makes the idea of a high breed intellectual incubation centre well worth it. One is not talking about anything that exists yet.

Doing so should be a TY’s last duty as they say. Some people would say that is elitism or pandering to ‘philosopher-king’ mentality. But neither Plato nor God excluded children of the poor from the benefit of biological exceptionalism, that being why we see children of the poor who are damned brainy, handsome or beautiful in physical terms. So, no contradiction! Such ‘students’ might be crazy by ordinary standards of reasoning but they are the ones in whose hands society’s fate would lie, because they can hear “the faint heart beat of utopia” and act like the proverbial intelligent wife. TY doesn’t owe the Middle-Belt or Nigeria any debt in this regard but if he doesn’t do it, he risks turning unhappily in his grave many, many years from now because there won’t be young people with the cultural constitution and the reflexivity to do what he did in his own time and how he did such things as to have emerged a colossus.

Series concluded