China is going through a complicated process of social transformation in which state intervention in the economy has brought about global scale prosperity but along with corruption, self-enrichment, inequality and poverty. Both left and right wing critics of the Chinese miracle are warning that the beautiful experiment could turn ugly by crashing disastrously although they do not agree on where such a crash would be coming from. The only thing they all agree is that no disaster will be coming to China from external enemies. Whatever happens to China could only be the paradox of success or the contradictions of her exceptional case of success in social transformation in human history. While right wingers see the problem in any failure or refusal to liberalise the economy into a market economy which corrects what they see as monopolistic practices of state backed firms, radicals see the danger in perceived abandonment of the principles of the official ideology of a ‘Socialist Market Economy’. But, both camps admit incredible degree of corruption, inequality and tension. They are on the same page with high State officials such as the 2007 statement by the then Premier to the effect that the Chinese economy is unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable.

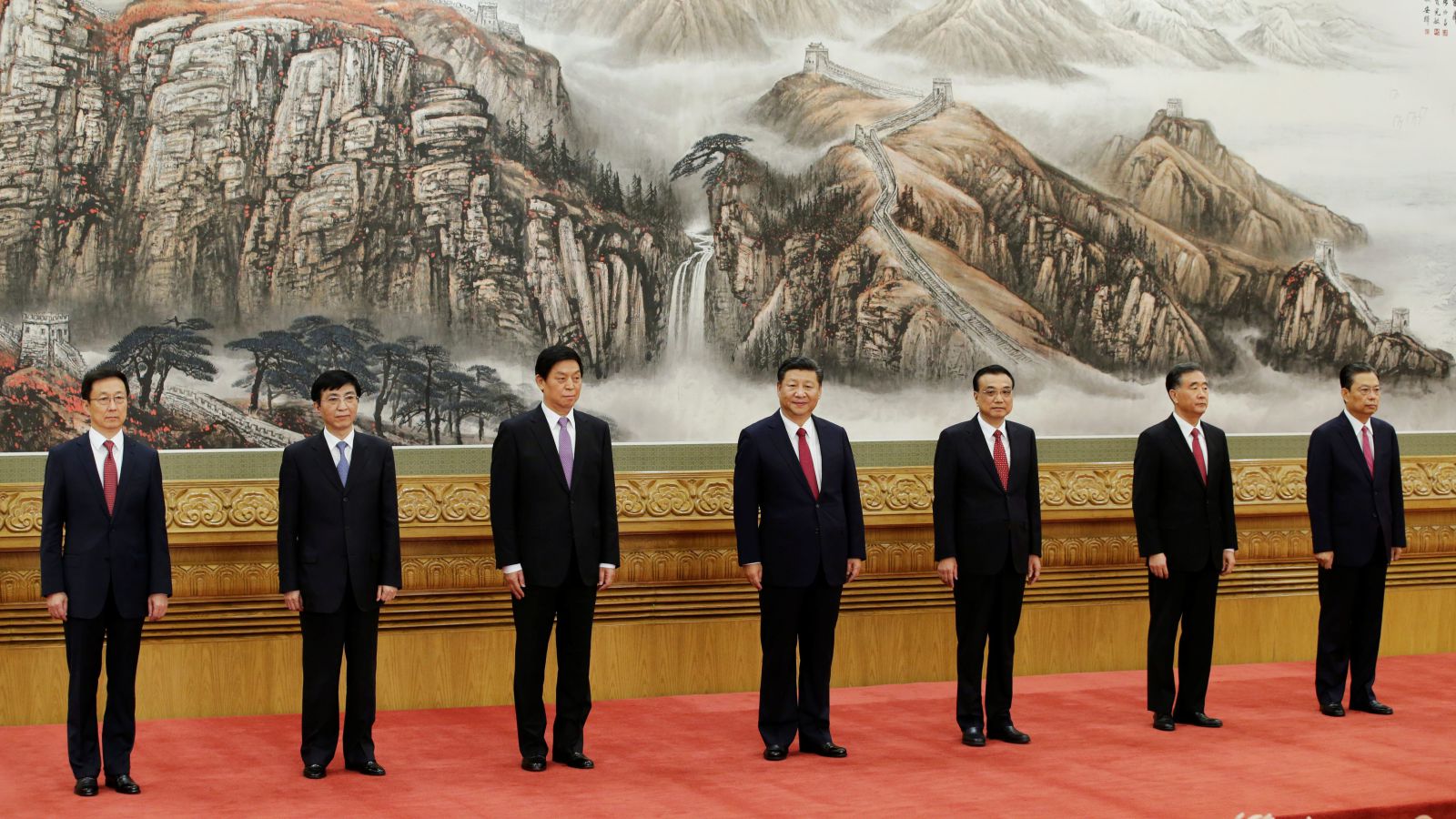

Within this context, what does it mean for President Xi Jinping to stuff the politburo with people who, by age, cannot succeed him in another five years when his tenure burns out and in the absence of clear layer of successors in the line up? What is the message in his inscription in the rule book in the status of Mao himself and Deng Xiaoping? Both Mao and Xiaoping have no competitors in terms of their place in Chinese history. While Mao was central to the revolution itself, it is Xiaoping who made the revolution real by the liberalisation strategy which has now made China to return to the world stage as a global power, a position it lost in the 19th century.

Look at what Deng Xiaoping brought about: modernity or even post-modernity

It was Deng Xiaoping who felt most stunned by China being left behind by the space of development in the Asian Tigers as to deliberately opt for global best practices in seeking development. Framed in the idea that “It doesn’t matter whether a cat is black or white so long as it catches mice”, Deng presided over a liberalisation process that consulted both within Asia and in the West, abandoned ideological puritanism and accepted importing whatever served the process, be it the reorganisation of the Chinese Central Bank in the image of the US’s, borrowing securities regulations from New York, London, and Hong Kong, including regulators from those financial climes, looking towards as far as Taiwan, France for models in diverse realms of managing the economy and, above all, insisting on educating Chinese children in Western elite universities, all of these towards achieving the reform. This was the opening up which coincided with the worldwide sweep of neoliberal model of capitalist accumulation in the late 1970s, the neoliberal phenomenon that foremost Marxist Geographer, David Harvey has called ‘accumulation by dispossession’ through liberalisation, privatisation and devaluation. The logic is that China, like most of Asia but unlike the entire Africa, had readied itself to partake in neoliberal globalisation in which Britain and the United States under Thatcher and Reagan were the enforcers. It was not caught unaware. This process accounts for the demi-god stature of Deng Xiaoping. He saw far into the future.

The problem now is that what Deng Xiaoping brought into being has borne pregnant fruits. China has achieved it but managing success is a completely different challenge. China is confronted with consolidating success of its spectacular economic achievement, securing the gains, managing complexity, handling the contradictions of corruption, deprivation, inequality, poverty and the tensions they all generate. There is a clear recognition of the role of power in managing this complex combination of challenges, especially as it concerns converting the achievement into power resources for global primacy. It has to think through the two options it has been presented.

Prof David Shambaugh’s 2016 book on China

Some of the most informed Western scholars of China such as Professor David Shambaugh speak of the possibility of China crashing down if it does not liberalise. While granting China’s possible distinctiveness, Shambaugh does not think the country is unique as to be able to cheat the fate that he says has befallen 90 out of the 101 countries that have struggled to beat backwardness between 1960 to date but which did not achieve that much desired transition into “fully mature economies”. Relying on the World Bank tracking of that process since 1961, he shows how only 11 out of these 101 countries beat the trap by liberalizing.

Radical writers such as Philip Huang disagree with the Shambaughs of this world and, instead, argue that China would be getting into trouble for deliberate or unintentional resort to circumventing the state’s own laws and regulations in order to enlarge the profit margins of enterprises. That is what he says is annulling the success of the state-led development in favour of gross social inequities afflicting China today, inequities which he says are all the more conspicuous in the eyes of the Chinese people who are contrasting the rhetoric of party-state’s continued espousal of socialism with the current realities and the relative equality of the Maoist past” when state enterprises were also under strict control. So, he thinks the way forward is not whether state firms should play a key role or exist at all, but rather where the profits of state firms go. Instead of the enrichment of capitalists, officials, and the state itself, resulting in current massive social inequalities, his preference is for a “socialist market economy,” as a mixed state and private economy that comes with social equity, summed up by the expression “getting rich together” since the state enterprises are, in theory, “owned by the whole people”. He is referring to what some others call the threat of“failure to rule by virtue”.

To make a choice from these two options, it is unlikely that the Communist party will take a plastic view of democracy and allow power slip around in the name of succession. What appears to be happening is a signal that grooming for Xi Jinping’s successor is still incomplete and more needs to be done, irrespective of global media panic that Chinese leader, Xi Jinping is transforming into an emperor in terms of becoming extraordinarily powerful. Two American newspapers, The Washington Post and Defense One would answer yes, somehow. The London based The Economist which is possibly relying on British intelligence analysis of Jinping has always suspected the man has been transforming into an emperor. Donald Trump and Western leaders are in awe of Jinping, it suggested recently.

Obama and Jinping

There is nothing to suggest that a Jinping has conquered the aphrodisiac called power but it is unlikely that he is following an agenda of personal power, with all the risks such would or could entail. By a 2012 testimony of Prof. Lanxin Xiang at The Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, the collective character of the present generation of Chinese leaders are no hardliners but people who would quickly embark on a serious reform should the system need it. Xiang rates the current generation as counter-intuitively the most mature in the Chinese history of generational rulership since the revolution. He claims for them a unique sense of history and political stamina in politics and foreign relations that will be decisive factor for the coming years. His idea of Xi Jinping is a tough, congenial but also pragmatic fellow whom he says has a life experience ahead of ex-US President Barack Obama.

Every China president is automatically powerful in military and non-military terms. The powers of any president of China, a country whose population is in the range of nearly a billion and half, a nuclear armed power and a member of the UN security Council is automatically better imagined than mentioned. All the elements of power are today in China’s favour – its image, its self-understanding as a power that wants to rise peacefully without imposing its will on others but interested in win-win outcomes and the complicated, contradictory economic experiment that has made it going on in the country. It is unlikely Jinping will step out of the rule book, written and unwritten and if he does, it must be in response to system self-correction. But, it is going to be a long wait!