The shape and contours of the model will only emerge from the brain workers gathering for the planning meeting in Addis Ababa from June 30th and July 2nd, 2017 but Afro-optimists across the world are already texting, tweeting and clinking glasses. They cannot wait for what everyone hopes will be the African moment in terms of securing its future through the performativity of a Continental Model AU. Enthusiasts salivating for the dawn of such a more imaginative attempt in continental self-representation are, in the meantime, casting their minds back to the closest version of the impending simulation of Africa by its own youths. That version is, unarguably, what started as the OAU Mock Summit at the Ahmadu Bello University, (ABU) Zaria in Nigeria from the late 1970s, berthed at the Command Day Secondary School at Lungi Barracks, Abuja in 2004 before relocating to its current base, the Anglican Girls Grammar School, (AGGS) in Abuja, Nigeria.

The shape and contours of the model will only emerge from the brain workers gathering for the planning meeting in Addis Ababa from June 30th and July 2nd, 2017 but Afro-optimists across the world are already texting, tweeting and clinking glasses. They cannot wait for what everyone hopes will be the African moment in terms of securing its future through the performativity of a Continental Model AU. Enthusiasts salivating for the dawn of such a more imaginative attempt in continental self-representation are, in the meantime, casting their minds back to the closest version of the impending simulation of Africa by its own youths. That version is, unarguably, what started as the OAU Mock Summit at the Ahmadu Bello University, (ABU) Zaria in Nigeria from the late 1970s, berthed at the Command Day Secondary School at Lungi Barracks, Abuja in 2004 before relocating to its current base, the Anglican Girls Grammar School, (AGGS) in Abuja, Nigeria.

Setting souls on fire on the Nigerian Television Authority, (NTA), Kaduna station in the 1980s was the OAU Mock Summit, making parents watching it to dictate ABU, Zaria the university of first choice for their children. A case in point is Hajiya Amina Salihu, one of the women making things happen today in Abuja power politics through the management of meaning. Watching a particular edition of the OAU Mock Summit, her father asked where the idea actually originated from. He got the answer: ABU, Zaria. And the father said, that is the university you are going. Hajiya Amina not only attended ABU, Zaria, she succeeded Professor Okello Oculi, the Ugandan born but Nigeria based Political Scientist who invented the idea of securing Africa by allowing the youths to imagine themselves as leaders, acquire an African wide world outlook in the process as well as certain skills, all of which could combine to produce the reality invoked.

Dr Dlamini Zuma, the then Chairperson of the AU Commission

Professor Oculi’s argument for this line of thinking goes like this. The first generation of Pan-Africanists came into that outlook as a reaction to racism and loneliness on European campuses for those who went to acquire education in the Western world and who subsequently politicised racism into Pan-Africanist activism. Africans were now being educated locally in the post independence era that terminated the rupturous European incursion into Africa. For him, that raised the question of how young people might acquire and sustain Pan-Africanist language and practice and, therefore, transcend ethnicity and localism if Pan-Africanism is not enacted on African campuses.

That was the broad argument with which he confronted Dlamini Zuma, the Chairperson of the African Union Commission in November 2013 when he was part of a panel that interviewed her for Kilimanjaro, an Africanist pullout published by the Abuja based Media Trust. Dr Zuma found the argument impeccable, having schooled in the UK herself and could testify to the truth of Oculi’s claims. It is in the context of this broad argument and Dr Zuma’s agreement with it that the Nigerian connection to the coming adoption of a Continental Model African Union makes sense. But there is the specific to the Nigerian connection which predated the meeting with Dr Zuma. That specific dimension has to do with the question of where in Africa or which African campuses might best serve the local brewing of Pan-Africanism? The ancient and geopolitical roots of Oculi’s answer to this question are the subject of the next section of this narrative.

In the mid 1960s, Professor James Coleman, the author of Nigeria: Background to Nationalism was the Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at Makerere University in Uganda where and when Professor Okello Oculi took his First Degree. Oculi was his Research Assistant at a point. He asked Coleman, an American, why he wrote his PhD thesis on Nigeria. Coleman told him that the professor who supervised his thesis had spoken to him about Nigeria as the country of the future, the kind of African country which would pay any social scientist to understood and always interpret correctly. Such a scholar would not only enjoy intellectual prestige corresponding to Nigeria’s strategic placement in continental affairs, s/he would also be a much sought after person by the policy mill.

In the mid 1960s, Professor James Coleman, the author of Nigeria: Background to Nationalism was the Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at Makerere University in Uganda where and when Professor Okello Oculi took his First Degree. Oculi was his Research Assistant at a point. He asked Coleman, an American, why he wrote his PhD thesis on Nigeria. Coleman told him that the professor who supervised his thesis had spoken to him about Nigeria as the country of the future, the kind of African country which would pay any social scientist to understood and always interpret correctly. Such a scholar would not only enjoy intellectual prestige corresponding to Nigeria’s strategic placement in continental affairs, s/he would also be a much sought after person by the policy mill.

Oculi took note of the answer, went on to obtain his own PhD in a well regarded American university before coming round to it. The time he got his PhD was also the time Nigeria was emerging as invoked by Coleman. Jean Herskovits, another American intellectual, profiled Nigeria in a 1975 article in Foreign Affairs as an African country which asked for nothing from anybody, gave preferences exclusively to African concerns and nations and borrowed nothing from anywhere to finance a civil war. For an Oculi well heeled in Pan-African ideals and activism, those were additional attractions for going to Nigeria beyond Coleman’s supervisor’s “political economy of research” argumentation.

So, when Crawford Young, Oculi’s own supervisor at the University of Wisconsin asked him why he wasn’t staying back in the US, Oculi answered by saying he considered it an imperative to take himself out of the reach of being slapped or deported or shot on grounds of resisting arrest, running away from the police or just for being black. He was hitting at the policing system in the US, mentioning nothing of what Coleman had told him about Nigeria. Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria was waiting for him. It was the star Nigerian university at the time in terms of overall radical scholarship and Pan-Africanist atmosphere. As he went into teaching, his Pan-Africanist gaze came alive. It did not take long before an OAU Club was born in the university.

The flag ship engagement of the OAU Club was the Mock OAU Summit by which ABU undergraduates simulated the OAU Summit. That meant role playing in such a way that enacted the continent, from the discursive, personality, mannerisms and inter-state differences that define it. It provided the students the challenges of researching whichever African country they were acting, turning the research into a policy option, train in the capacity to hold an audience/overcome stage fright and generally begin to emerge as a leader rather than someone just pursuing a degree in terms of a meal ticket. In other words, the role playing had transforming as well as transformative impacts.

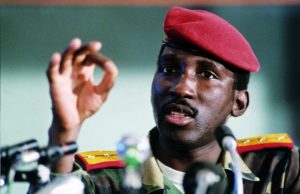

The late Capt. Thomas Sankara of Burkina Faso

It did not take time before the more dramatic elements of the Mock Summit – the swagger sticks of African presidents, the walking sticks of those of them who used one, the beards, the dress pattern, the speech mannerisms and the ideological stunts and taunting – began to define the entire project. The popularity soared after each performance. It was normally staged at the Main Campus first, then taken to Kongo Campus, all in ABU. Then it was taken to the University of Jos followed by Bayero University, Kano.

In 1983, Dr Kabir Mato, one of the super stars of the OAU Mock Summit, added his own dimension to the spread of the bush fire. Posted to Benue State to serve in the National Youth Service Corps scheme, he gathered all those he could and staged a Mock Summit in the NYSC Camp. So impressed were the actual and the virtual audiences that NYSC State Directors started sending their ABU corpers to ABU, Zaria to collect script of speeches. They were to learn that there were no such ready made speeches to be collected. Each student acting any particular Head of State had to research his or her own speech, edit and make it good fit in all respects.

In those days when there was not yet the internet, it might have gone nowhere beyond these campuses if NTA, Kaduna did not catch the bug. In pursuit of the spirit of public broadcasting which undergirded the pre-commercialisation NTA, it literarily took the programme over because it was popular beyond the campus. The audience always thought it was something actually happening in Addis, the OAU Headquarters. Professor Oculi recalls how NTA, Kaduna recorded and condensed one of the outings into a Network airing in 1988. The Federal character of NTA meant that other NTA stations could access and show the programme at their own local convenience. An idea had acquired its own autonomy.

Beyond NTA, it had also found purchase with leading players on the campus and outside of it. Professor Abdullahi Mahdi who was the Dean of Social Sciences then went as far as accompanying the students to a performance at Durbar Hotel in Kaduna. The Durbar performance itself was sponsored by Mallam Mohammed Haruna, a kingpin of the erstwhile New Nigerian Newspapers. When Dr Moddibo Ahmed Mohammed was in charge of the university estate, he readily provided the students with buses for their trip, including fuelling and the allowance for the driver. Given his closeness to Professor Nayaya Mohammed, the ABU Vice-Chancellor at the time in question, his own support was interpreted to mean the VC’s approval and support.

Prof Okello Oculi

To this extent, the OAU Mock Summit was a great idea going great. But trouble was already on its way. The Nigerian establishment had reasons to dislike the Mock Summit tradition. Unfortunately, Professor Oculi either didn’t get the message or did not read it correctly, partly because he thought the messengers who delivered the ‘protest’ would take it upon themselves to brief those who sent them. Military officers studying at ABU, Zaria and participating in the club or knowledgeable about how it operated were telling the professor that Jaji wasn’t happy about the staging the summit because it was all about mocking African leaders. There was no way the military would confuse simulation with mockery, simulation being at the heart of the military profession. So, when they confused it with mocking, it should have registered in Oculi’s head that it was a coded language. Oculi’s reply suggested that he didn’t get the message. “Are you giving them the correct situation”, he would ask the military students. “I said to them, but you are students and participants. Did you see any ridiculing of any African leaders in the way we do this thing”?, he would ask the students.

Assuming that it was actually Jaji that was unhappy, how were Lieutenants and Captains expected to go and give any ‘correct situation’ to the Major-Generals, Air Vice-Marshals and Naval Commodores running the show there? Secondly, in a Mock OAU Summit in which the most sensational or most popular ‘African leaders’ were the Gaddafis, the Thomas Sankaras, the Jerry Rawlings and other radical Heads of state at a time of unpopular leaders at home, Jaji here could not but mean the Nigerian establishment. Coming especially after the brouhaha between Nigeria and Libya in 1981 over the renaming of Libyan embassies as People’s Bureau which Nigeria rejected, it ought to have been clear it wouldn’t be long before the OAU Mock Summit got into trouble if the student playing the role of Gaddafi is one of the most popular in Mock Summit watched nationwide.

Oculi does not quite accept this explanation. He has his which is that the smashing of the OAU Club is no different from the smashing of popular organisations such as the Nigerian Medical Association, (NMA), the National Association of Nigerian Students, (NAS), the Academic Staff Union of Universities, (ASUU) and so on once the Babangida regime had taken IMF conditionalities and could foresee opposition building up. What is important is that it was another version of the order ‘destroy everything that moves’ in the smashing of the OAU Club and its OAU Mock Summit. Although it is said to be alive in not only ABU, Zaria but also its senior brother, Bayero University, Kano aka BUK, some people would argue it is the shadow of the old OAU Club and its hair-raising Mock OAU Summit.

But it has been a case of OAU Club is dead, Long Live OAU Club. When Professor Oculi left ABU, Zaria, he did not leave behind the Pan-Africanist paradigm behind the mock summit. But he scaled it down to secondary school level, partly because he was done with working in the university system anymore, meaning the end of living on any campus. But he was not comfortable with not doing anything about Pan-Africanism. So, something was born in that respect, initially with the Command Day Secondary School at Lungi Barracks in Abuja before the relocation to the Anglican Girls Grammar School, also in Abuja.

Their Excellencies at work

It was for them he made the request to Dr Dlamini Zuma to facilitate their trip to Addis. Dr Zuma was the Chairperson of the African Commission then. That was November 2013 when Oculi was part of a panel that interviewed her. But she said that the African Union did not have the resources to transport the students Oculi had been grooming in Abuja to AU Headquarters to stage a performance. Instead, she suggested Oculi see Baba. By Baba, she was referring to former president of Nigeria, Olusegun Obasanjo.

According to Prof Oculi, Dr Zuma said that return ticket for 20 or so students would not be a problem for Baba. He knows Dangote, Otedola, Elumelu and co. They will bring the money if he calls them, the Chairperson said. Oculi asked her if he could go tell Baba that Dr Zuma sent him. Dr Zuma said yes, “Go and tell him that I am the one who sent you after him”. Back in Abuja, Oculi tried to get in touch with the former president. He sent a DHL which got no response. Then someone gave him a name who facilitated the contact, almost magically. Within so short a time, he got a reply from Baba, a positive but very disappointing one. Baba sent only two tickets when at least 21 were needed. The AU Headquarters wasn’t amused. It suggested that the former president is no less as araldite as he ever was, although it is unclear if the African Leadership Forum took the decision or Obasanjo personally did.

Without 21 tickets, the idea of the students taking tea with Dr Zuma at AU Headquarters died. But Oculi and the school authority as well as the students managed to select two girls to utilise the two tickets to Addis and show the big people there the stuff their Pan-African Club is made of. The next hurdle was accomplishing the journey which widened the dramatis personae to Dr Akinwumi Adesina, Nigeria’s Minister of Agriculture under the Goodluck Jonathan Presidency. Tagging along Mrs Kate Bello, their school principal, the two students were at the Ethiopian Embassy in Abuja on the day they were to fly to Addis to perform at the ‘Africa Youth Summit’ that year. That was what they were told to do so as to collect their travel papers. But the game changed. They were told they could not travel because they had no invitation from Addis. When this was filtered back to Addis, Addis said they should make the journey, that they would get visa at the airport in Addis. So, a big rush to the airport in Abuja began.

Backed by their principal and Prof Oculi, the two students headed for the Abuja airport nevertheless. They made it there only to be told it was too late for them to board. The school principal, Debrah Ogazuma, Professor Oculi’s wife and the teacher in charge of the Pan-African Club formed an instant resistance movement, insisting the students must travel. But the Desk officers at the Ethiopian airline were even more adamant. No explanations would move them except that before the students declared mission impossible, a miraculous process began to unfold. Dr Akinwumi Adesina, the then Minister of Agriculture arrived at that spot. Oculi who had never met him before approached to explain what was playing out. The Minister tried to convince the Desk officers but they were not making any concessions. He left after telling the students not to allow the experience dampen their interest.

The teenage diplomats with Dr Adesina in Addis

But before the emergency ‘resistance movement’ finally left the spot with the two students back to Abuja, two security officials could be seen hurtling themselves at a great speed looking for the girls. Dr. Akinwumi had obviously and quietly gone to a higher official upstairs and cleared the crease. That was how, to everyone’s surprise, the students magically found themselves in the plane to Addis that day. It made all the difference because their own presentation was in the morning the next day. There was no second chance if they did not travel that day. From the flight to Addis, through the event and back to Nigeria, Dr. Akinwumi became their guide, guard and protector, assigning his assistant to that job.

Meanwhile, Obasanjo happened to be at Addis too as a co-sponsor of the youth fiesta with Dr Zuma. It was here that he assumed ownership of the two girls, making them his granddaughters. Asking them to seat, one on his right and another at his left, was a signal that nobody could intimidate them. Clearly, the twosome had impressed the audience in presenting a mini version of the summit by playing multiple roles in quick succession but, more importantly, in the maturity of their intervention at the discussion session on promoting agriculture in Africa. It showed they had reached the level of opinion which could not be dismissed. It was a product of their sessions and speech researching during their practices with Oculi. Thereafter, Obasanjo took charge. The Agric Minister ensured everything worked for them in Addis. They had become government children on national assignment, an assignment they were doing very well, especially being able to hold such an audience. Practice makes perfect, they say.

This is the long history of the pedagogical trajectory of Pan-Africanism in Nigeria, something that might be of interest to the planning committee, especially if they are considering a place for the three Nigerian schools that have been the breeding grounds – Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Command Day Secondary School, Lungi Barracks and the Anglican Girls Grammar School, Abuja in working out the continental model. For Professor Okello Oculi, this must be God’s own time for an idea he foresaw several decades ago to become the heart of continental self-understanding and self-renewal in African international politics. When God says something, someone or an idea is right, all other things are immaterial!

This report will be concluded in part 2, devoted mainly to the moving reportage of the Addis Ababa trip by one of the two girls. It is worth reading by all parents, school administrators, critical observers and the government.