*China is doing good in Africa but Africa should not allow China to violate international labour laws by using prison labour

*Africa is not heading for recolonisation but dependence

*The ‘balkanisation’ of Africa is the original sin and the main reason for the fragility of our states

*Attrocities are not unique to Africans, violence simply brings out the worst in human beings

*That is why it is so important to prevent violence

Prof Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja

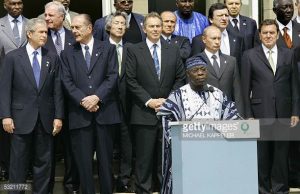

What do you make of Thabo Mbeki openly cautioning against uncritical celebration of ‘China in Africa’? He is one of the very few African leaders who said so.

Well, like I said the other day, China has just completed two brand new railroads: Djibouti to Addis Ababa, Mombasa to Nairobi. They are also the only country that built the first railroad in post colonial Africa: Dares es Salam to Lusaka. So, the question is who else is going to do it? I am sure that the Germans can build railroads, the Belgians were the best railroad builders in the 19th century. And they took railroad technology to Argentina, to Asia and so on but they are not building anything in Africa. So, as I said, our major task is to make sure that China includes African workers in their projects and we force them to build things of high quality, not leave them to put up things that are going to break down in few months. That’s our responsibility. They are a power that is interested in our resources, they have the right to participate in international trade, we should sell them things but we have to make sure we protect our interests as they protect theirs. So, it is not just a matter of taking a position. If you take that position, you have to it against all the countries in the world, not just China in isolation.

China has a discourse of ‘China in Africa’. Beyond the overarching strategic notion of ‘Peaceful Rise’, they have the Win-Win discourse to underpin ‘China in Africa’. Does Africa have a discourse of China?

Africa does not have a discourse of China. The Daily Nation in Nairobi said China has an African policy, Africa does not have a China policy. Let’s make a China policy. And China policy should mean we should ban too many Chinese workers. I gave the example of Angola – 250, 000 labour contracts with Chinese workers. That is obscene. It should not be allowed. I am sure there are Angolans who can learn whatever skills needed in terms of building roads and working on whatever the Chinese are working on. That can be done!

By which logic might we understand this particular tactic on China’s part?

It is not China. It is Angola then. China can bring whatever type of workers but you can stop them.

But what is the impulse?

Because China is a country that is highly populated. And some of the labourers are prisoners. These are prisoners, staying in one place like a dormitory and when they get out to the market to buy food and other things, they are accompanied. You will see people who do not look like the rest of them. These are the police, the guards. So, they were prisoners. And prison labour is very cheap. And that’s why they are using them. So, they have extra hands to use, to employ. That’s why we should not allow them to do it, we should not allow them to violate international labour laws in using prison labour. But, in Africa, we allow them to do it.

Recolonisation or liberation?

When you add neoliberalism to ‘China in Africa’ and put it together with the convergence of global interests in Africa’s extractive industries, are we heading for recolonisation or for liberation?

No, I don’t think we are heading for recolonisation but simply that we are continuing this neo-colonial practice of dependence. Walter Rodney wrote that brilliant piece which he did before the 6th Pan-African Congress in Dares es Salam in 1994 that African leaders betrayed the cardinal principle of Pan-Africanism when they made the pact with the colonialists to accept the balkanisation of Africa. That is one of the most brilliant analysis that has come out since independence. You see, I can show you we have 20 countries in Africa that do not have to exist. Instead of 20, we could have had just four.

French West Africa of eight territories – Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan now called Mali, Guinea, Upper Volta now Burkina Faso, Cote D’Ivoire, Niger and Dahomey. Togo was a UN Territory. So, when you add Togo, they become nine. All of these territories were governed from Dakar which was the capital with one Governor-General and governors in each one of the other territories. Why should they break up into nine states? They could have made one state and it would have been a great country. French West Africa could have taken whatever name, be it Ghana or Mali or whatever. It would have been a wonderful state, it would have been strong but France didn’t want such a strong state. They didn’t want a state like that because they would not be able to manipulate it.

Then you go to central Africa, we had French Equatorial Africa made up of Congo now Congo Brazzaville, Gabon, Chad and Ubangi-Shari, now Central African Republic, (CAR) Plus French Cameroun as UN Territory, it makes five territories governed from Brazzaville by one Governor-General. Instead of one country, you have five. Then we go to Belgian Congo. Belgian Congo and Ruanda-Urundi! Instead of one country, you have three. When I was growing up, I didn’t know they were three separate territories because it was one single army and so on.

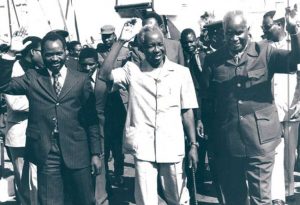

Then you go to East Africa, there were three different colonies – Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. But they had common services – habours, railroads, universities, telecommunication and so on. I spent a week with Nyerere before he died. He said he proposed to the British, to Obote and Kenyatta that Tanzania would wait to have its independence at the same time with Uganda and Kenya. They all refused. And so, Tanganyika became independent in 1961, Uganda in 1962, Kenya in 1963.

Julius Nyerere in the middle of Samora Machel and Kenneth Kaunda

So, you have 20 countries instead of four. We have three countries in East Africa instead of one, three in Belgian Central Africa instead of one, five in French Central Africa instead of one, nine in French West Africa instead of one. Just imagine that. That balkanisation was the original sin and the main reason for the fragility of our states. If we were able to maintain huge structures, which meant that the more qualified people would have been on top, but again it required people who were really independent because we saw how the Mali Federation broke down. Senghor and Modibbo Keita insisted they were not going to follow Houphouet Boigny in balkanisation. They were going to keep the two countries, Senegal and Mali in the Mali Federation. But it didn’t last long. A couple of months later, they broke up because there were disputes between Senghor and Modibbo Keita as to who would control the country. The French were working with Senghor, saying this Modibbo Keita was Socialist, communist, bla! bla! and Senghor caved in and the two countries broke up. But I am sure that if we had larger units, it would have been much, much more difficult to break them up and we could have had countries such as Brazil. Look at how big Brazil is.

So, that was the original sin and the main reason why we have fragile states. Look at Cote D’Ivoire a month ago where military units were confronting each other on the streets. The presidential Guard against the gendarmerie because of all these nonsense created through questions of ethnicity, region and all that. So, I think that is where our main weakness lies. And today, we are hesitating in moving forward into integration. That is another weakness because the more integrated we become, the greater we would be in defending our interest again foreign interests. Otherwise, we are going to be manipulated forever and of course, we have leaders who want to cling on to power like the Mugabes, the Biyas, the Obiangs and Dos Santos and Kabila and others. That’s not going to help us.

I am still not clear if it was because the proposal came mainly from Gaddafi but the opposition to governing Africa as a central entity was so fierce during the debate on the nature of African Union between 1999 and 2001. The ministers of foreign affairs could not have done that if that was not the position of their presidents and prime ministers as much of that was live media affair, one way or the other. So, where are we between you and the reality on the ground?

President Joseph Kabila of the DRC: One model of the agency problem in African international politics

These are leaders with no vision. They have no real interest in people’s welfare. Look at the some of the leaders. President Kabila of the DRC is an O’ Level graduate, a taxi driver. He spends most of his time watching videos and television, playing Nintendo, riding fast cars and motorcycles. These are what he spends most time on. Matters of state, he doesn’t care, he doesn’t even understand half of it. The Prime Minister comes, he sends him something, he signs because he has very clever advisers, tough economists and intellectuals who are advisers. They look and advise and he signs. So, the people’s welfare is the list of his worries.

Didn’t he have some training and exposure in China?

He spent very few months there. It was military training, it didn’t last long. He went to China, then the war broke out in August 1998, he was rushed back and appointed Major-General. I was talking to some military officers in Burundi who fought in the war which expanded to Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi against the Congolese and their Zimbabwean allies. And an officer said Kabila was just overwhelmed and he didn’t know what to do. He said no battle plan worth the name in terms of confronting the enemy. He said he fled and they were left with all the ammunitions, trucks, jeeps, mortars and machine guns. So, that’s the kind of guy we have, you know. So, he’s not even competent for the job of being a military man. How can he be competent in running a government? So, this is one of the main problems.

So, when you put all these together, are you pessimistic or Afro-optimistic?

No, I am always optimistic because of the resilience of the African people. We have always been a resilient people. We went through Arab slave trade, transatlantic slavery, colonialism, all these years of useless leaders like Idi Amin, Mobutu, Kabila and we have survived all that. All these people will die and go. Some more crazy ones may take over but sooner or later, we would have the good people to run our countries. We have also produced the Sankaras and some leaders who have shown us that it is possible. Even Kagame has tried.

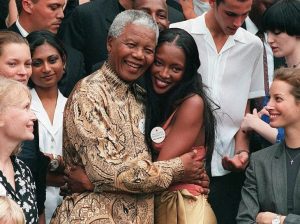

The beautiful model of agency in Africa’s international politics: the late Nelson Mandela in a protective embrace of the black model, Naomi Campbell

So, hybrid of the good, the bad and the ugly will see us through eh?

Yea, yea! Our resilience too. We will be able to make it

But, at the University of Abuja, someone asked you a question that connects with what Soyinka once said about the African and violence. I am not sure now but I think it was Soyinka who said it that any people that could afford to sell their own brothers into slavery as Africans did must have a problem. And that person who asked the question at University of Abuja wondered how it is possible for Africans to be killing their own brothers for three months nonstop as it happened in Rwanda and is still happening in South Sudan. He said that to kill a chicken is even a problem for some people but in Africa, we do it to each other all the time in the most cruel and horrific manner.

I think it is the heat of the action. For example, you have heard of cases of people engaging in cannibalism. In a normal situation, you won’t have an African eating another human being. But in conditions of war, where people have been drugged, it is another thing. Many of our soldiers go to battle drugged. I saw a Captain in Lubumbashi, he was telling me how they were able to take Bukavu during the so-called rebellion of 1964. He said I took a lesson from our Belgian officers during the colonial period. They use to drug us before we go to fight because a drugged soldier is an animal. In that condition, the difference between a goat, a child and women doesn’t exist. It is like the General in Namibia and the order he gave about destroying everything that moves in the village – men, women, children, animals, anything that moves. This is what happens. These soldiers are drugged and are able to do nasty things that a normal person wouldn’t do. If we are going to create armies that are really trained in the art of war, that are disciplined, that are told you don’t touch certain category of people even in war. So, the question is what has changed. I think drug has to do with it, certainly the heat of war too. I don’t know of plausible other factors, perhaps psychologists have to help us understand that.

You have touched on a different dimension of the African crisis – what passes as the animalism of military people by normal standard of reasoning. But that is different from the cruelty, the culture of horrific, scorched earth operations we see in communal or ethnic conflicts, perpetrated by youths, war lords and terrorists. And I am asking whether you don’t think we could have a problem peculiar to us. Here, in Nigeria, it is heroism to call for mass violence under whatever pretext without any thought for what would happen to children, women and those who have no voice in the matter. In Rwanda, it went on for three months. Even animals stop fighting at a threshold. Could it be we have a problem of what a Nigerian Professor of Political Science has called endemic catastrophe?

You have touched on a different dimension of the African crisis – what passes as the animalism of military people by normal standard of reasoning. But that is different from the cruelty, the culture of horrific, scorched earth operations we see in communal or ethnic conflicts, perpetrated by youths, war lords and terrorists. And I am asking whether you don’t think we could have a problem peculiar to us. Here, in Nigeria, it is heroism to call for mass violence under whatever pretext without any thought for what would happen to children, women and those who have no voice in the matter. In Rwanda, it went on for three months. Even animals stop fighting at a threshold. Could it be we have a problem of what a Nigerian Professor of Political Science has called endemic catastrophe?

Well, atrocities take place in all wars, in all conflicts. When you talk of women being raped in war, it is done all over the world, including Europe. See what happened in Bosnia and Kosovo. Some people who were there can tell you really horrible stories. Women were raped, children were killed. Violence brings out the worst in human beings. It brings out the worst. And certainly also, we are a people used to fighting with machetes and, unlike guns, it is horrible. That is why it is so important to prevent violence. Once it reaches violence, you are going to have the kind of situation you are talking about. It is never a pleasant picture.

There has been a huge return to the study of representation of Africa in the global media. Gagliardone, Wasserman, Nothias, Scott and many other scholars have churned out scholarly works since The Economist reversed itself by posing ‘Africa Rising’ to its cover story of ‘The Hopeless Continent’. Earlier this year, Africa’s Media Image was republished with 21st century now added to the title. Could it be the global media is telling a different story of Africa?

You see, I don’t give a damn because the papers are going to continue being racist and being condescending but we have to remind them as Okello just pointed out, remind them that this brutality, that some of these things came out from the lessons Africans drew out of European colonialism. Look at what the British did in Kenya. All these things you say Africans do to each other, the British forced their own soldiers to commit such atrocities in Kenya against African people. And the French in Algeria. It was horrible. I don’t give a damn what The Economist says. It has no impact on me whatsoever. And what New York Times and all these papers say. No. They should look into their own backyard, their own history, what kind of atrocities they have committed before. We saw what the Americans did in Vietnam and what they did in Iraq. Sometimes people say that some type of savagery is worse than others. Well, all wars is savagery, all killings is savagery. We might take offence in some of the extent in which some of the soldiers or our people go in the use of the bayonet and machetes but killing is savage and we should stop all killings.