It started first in Nigeria when three former Heads of State – former President Olusegun Obasanjo, Ibrahim Babangida and Abdulsalami Abubakar met and took whatever collective position presumably on President Muhammadu Buhari’s health. That was last Monday, May 1st, 2017. Then on May 5th, 2017, three former presidents in South Africa- Frederick de Klerk, Thabo Mbeki and Kgalema Motlanthe – followed suit saying, in the words of Mbeki, that “the rose planted by the country in 1994 is sick”. Both interventions suffer the interpretation of gentle pressures on both incumbent to go.

The three ex-South African presidents on a mission reclaiming task

But while the revolt of three former presidents in South Africa is specifically against incumbent’s corruption as pronounced by the courts and the associated loss of moral authority, the intervention in Nigeria lacks that precision because incapacitation in Nigeria is tied up to the national question muddle in the country. For instance, an article overflowing with venom is already circulating on the social media veering on where the trio of Obasanjo, IBB and Abdulsalam got the moral authority for their intervention. The menacing tone is as if the trio are no longer citizens. In South Africa, there is also a rejectionist voice against the intervention, especially by those who disagree with Mbeki’s call for dialogue as a way out.

Yet, in spite of the highly justified regular criticism of the trio in Nigeria, they along with few others constitute the national cohort at the moment. Everyone craves for their exit from politics but they are still the reality as long as no alternative movement with a binding narrative of Nigeria has emerged. In a divisive issue such as whether an incumbent should go or stay, they remain players with interests. Whether the interests are that of Nigerians or their own personal interests or whether a neat separation between their personal and national interests is possible is a matter for debate.

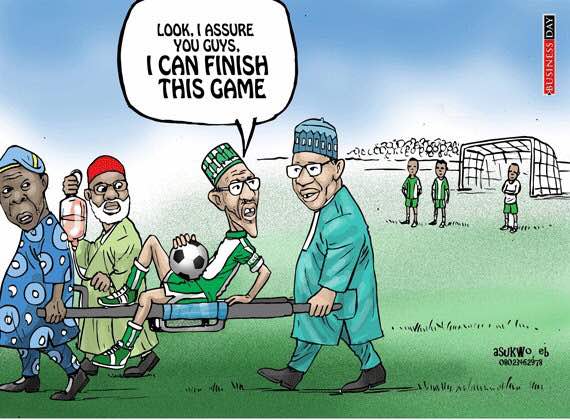

Additionally, the intervention in the case of Nigeria is coming at a time of a clear divide in Nigeria over what should happen now in respect of the president’s ill-health. There are those for and those against Buhari’s exit to look after his health. Those for his exit argue that he is medically incapacitated, leaving some unknown persons exercising powers in his name, amounting to power without accountability. On the other hand are those who insist that the president is not so sick or incapacitated and that the agitation for his exit is part of ‘corruption fighting back’. His appearance in public for Friday prayers yesterday got his supporters stirring even as Governor Fayose of Ekiti State would say Nigerians did not elect a president who appears only weekly in the State House Mosque. Each camp has its spokespersons, agitators and anchormen and women. It is a discursive battlefield or promises to become a full one very quickly.

APC mandarins

What is the truth of the matter? Unfortunately, this is hardly a matter for truth to settle because truth itself is a product of the power over interpretation of details. There is no such thing as truth standing out there that can be discovered through careful scrutiny of facts or details. Truth, like knowledge, is always constructed. Although the constitution says that the president can be removed for incapacitation, the question is what or when is a president incapacitated?

Ordinarily, the president’s dwindling public appearances, especially absence from the Federal Executive Council, (FEC) meeting three times running should be part of the proof. But Alhaji Lai Mohammed, the Minister for Information says it has nothing to do with incapacitation but adherence to the president’s doctor’s advice. Before the minister’s intervention, the president’s wife said the health status of the president has not reached the level being speculated. And before her, Femi Adesina, the presidential spokesperson said the view of one person calling on the president to resign could only make sense if mapped unto the aggregate standpoint of the millions who voted in the president.

But what are the president’s defenders up to? They are bidding for power. That is power as the ability to define what is normal, what is acceptable or how to make certain things natural irrespective of the power agenda hidden in that naturalization. So, if the president’s defenders do not find their match in counter-discourses, then the position that three times absence from FEC meeting is very normal becomes commonsensical, normal and accepted.

Divided enclave

Fortunately or unfortunately, Lai, Adesina and Mrs President have got replies. The meeting of the trio of Obasanjo, IBB and Abdulsalami Abubakar, three former military heads of state, is being interpreted in some quarters as gentle pressure on the president to resign. Another retired General, Alani Akinrinade, is saying he regrets fighting the civil war, an indirect critique of what is. Chief Bisi Akande is speaking in tongues. Ebun-olu Adegboruwa, the Lagos lawyer who started it all last January is now asking the Senate to declare the Office of the President vacant and swear-in the Vice-President in acting capacity. He is also planning to mobilise for the realization of the president’s exit. Earlier on, some civil society activists advised the president to go on medical leave to take good care of himself. Some observers read them as diplomatically canvassing his exit because of the time the president is speculated to need to complete the treatment vis-à-vis the constitutionally stipulated time a president could be out of office and still come back to reclaim it.

In other words, two dominant camps have emerged over how Nigeria might handle presidential ill-health. In 2010, the shouting match that went on in the name of a debate on zoning was resolved with a ‘Doctrine of Necessity’ invented and operationalised by the National Assembly. ‘Doctrine of Necessity’ was a creation of power through discourse before it became a bureaucratic reality. But, in this case and at this point, the balance of social forces is such that a ‘Doctrine of Necessity’ is unlikely obtainable. It shows how meaning changes.

With the elite that Chidi Amuta, for instance, imagined in his Foreword to Adeniyi’s book, it is difficult to see the irrelevance of the intervention of the Nigerian trio who, individually and collectively and in quick succession, constituted today’s elite across all realms. Unlike in South Africa where the intervention is a rebuke and a call for dialogue, the nature of the intervention in Nigeria is still unknown. It is still military style politics. The point about the Nigerian stalemate is the point about balance of social forces. There is an incumbent whose followers are so intolerant in language and attitude to anyone who doesn’t see Buhari’s anti-corruption war as answer to everything just as there are others out there who believe Buhari is now no more than a waste of the country’s time. This balance might recommend opening up the inter-subjective space as a way of managing the current stalemate without injury to national stability. Opening up the inter-subjective space means arranging for and achieving consensus through ‘civilized conversation’. In such conversation, there is no room for those who start by threatening fire and brimstone because such people make communication impossible and, therefore, conflict possible.

Dr Goodluck Jonathan of Nigeria and President Jacob Zuma of South Africa, last and incumbent leaders of the embattled two leading parties in each of the two countries

Still, the question is whether the two interventions in the two countries can be understood by a ‘domino effect’ framework or as just a coincidence? What is the potential of this trend as a disciplining move against incumbents in Africa, irrespective of what an incumbent might be in breach of at any particular time? It is important noting how developments in Nigeria and South Africa have been replicating each other since 1999. Of note in that is the way the dominant party in each of them has been failing. The People’s Democratic Party, (PDP) in Nigeria crashed out of power in 2015, the African National Congress, (ANC) is coasting to that status if recent electoral misfortune is anything to go by. While the PDP in Nigeria does not have the legacy of the ANC in terms of a national liberation orientation, it was formed by some of Nigeria’s most advanced politicians. Its collapse is thus a subject worthy of serious reflections. This is more so in the light of the devastating excoriation of elite leadership in Chidi Amuta’s testament in Segun Adeniyi’s Against the Run of Play. It goes thus: They have no political ancestry, being mostly political orphans with no solid convictions or even ethical moorings or moral qualms whatsoever”.