Abubakar Rimi’s Graveside and the Travails of a Tendency in Nigeria

By Adagbo ONOJA

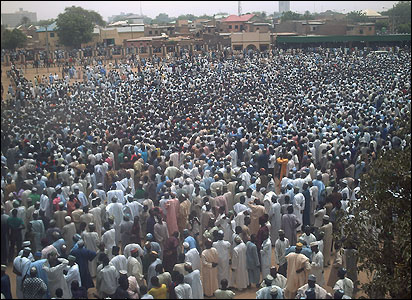

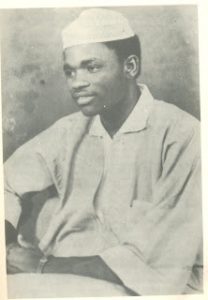

A few days ago, someone circulated an existing picture of the graveside of Alhaji Muhammadu Abubakar Rimi who passed on April 2010. It is not clear why the picture is being circulated now since it is not April yet as to connect it to the 7th anniversary. Nevertheless, Abubakar Rimi, with his unforgettable visage, remains an instant reminder for many of a tendency that still has a soul but not a body anymore. In other words, what used to be known as the radical tendency in the north cannot be located. That is a bit surprising for a movement that transformed into the first political party in the region – the Northern Elements Progressive Union, (NEPU). It successfully held out against waves of repression by the Northern People’s Congress, (NPC) in the first Republic. By the late 1970s, it transformed into the People’s Redemption Party, (PRP). The PRP had membership that included the Wole Soyinkas, Chinua Achebes and Bala Usmans of this world. The peak was winning Kano and Kaduna in the 1979 elections, a feat it described as distorting the ideological homogeneity of northern Nigeria the defunct National Party of Nigeria, (NPN) would have loved to present to the world. Then, from that peak, it began a descent, from one calamity to the other.

A few days ago, someone circulated an existing picture of the graveside of Alhaji Muhammadu Abubakar Rimi who passed on April 2010. It is not clear why the picture is being circulated now since it is not April yet as to connect it to the 7th anniversary. Nevertheless, Abubakar Rimi, with his unforgettable visage, remains an instant reminder for many of a tendency that still has a soul but not a body anymore. In other words, what used to be known as the radical tendency in the north cannot be located. That is a bit surprising for a movement that transformed into the first political party in the region – the Northern Elements Progressive Union, (NEPU). It successfully held out against waves of repression by the Northern People’s Congress, (NPC) in the first Republic. By the late 1970s, it transformed into the People’s Redemption Party, (PRP). The PRP had membership that included the Wole Soyinkas, Chinua Achebes and Bala Usmans of this world. The peak was winning Kano and Kaduna in the 1979 elections, a feat it described as distorting the ideological homogeneity of northern Nigeria the defunct National Party of Nigeria, (NPN) would have loved to present to the world. Then, from that peak, it began a descent, from one calamity to the other.

As then

Abubakar Rimi and Balarabe Musa, the PRP governors of Kano and Kaduna states rebelled against the leadership of Mallam Aminu Kano, joining their counterparts in the old Unity Party of Nigeria, (UPN) led by Chief Obafemi Awolowo; the Nigerian People’s Party, (NPP) led by Dr Nmandi Azikiwe and the Great Nigeria People’s Party, (GNPP) led by Alhaji Ibrahim Waziri. While the ‘Nine Governors’ meeting these opposition parties formed served as a conscious opposition to the National Party of Nigeria, (NPN) and its capacity for arbitrariness, the rebellion robbed the PRP the opportunity and ability to have consolidated anything similar to what Awolowo did in the south-west through free education. In any case, Balarabe Musa was eventually impeached in 1981 by the NPN dominated Kaduna State House of Assembly, thereby denying that state the services of the governor and government that would have solved some of the problems being encountered today in that state, particularly Southern Kaduna crisis.

Dr Bala Mohammed, the late Political Adviser to the late Rimi

A February 1998 picture

In July 1981 too, Dr Bala Mohammed, the Political Adviser to Rimi in Kano was killed in a mob action. It was darkness at noon, a tragedy for an individual and for the tendency. In 1983, the eclipse came in the Buhari coup which some people interpret as basically aimed at terminating the potentials of the PRP as members of the progressives were winning elections and displacing conservative candidates in Niger, Adamawa, Kaduna and so on.

By the time the Abdulsalami Abubakar transition programme began to unfold in 1998, Abubakar Rimi was the single most dominant figure symbolising the tendency. He, along with Sule Lamido, ended up being part of an all tendency negotiation of the future in terms of the formation of the People’s Democratic Party, (PDP). But in the formation of the government, Rimi was eased out. He neither emerged the Vice-President nor Foreign Affairs Minister he was speculated. The then president, Obasanjo made his choice in which Atiku Abubakar from a different tendency emerged as Vice-President to Obasanjo in 1999 while Sule Lamido who could be called second in command to Rimi at that time was made the Foreign Affairs Minister in the Obasanjo regime. After the initial confusion, Rimi and Lamido parted ways, reconvening only after Lamido became governor of Jigawa State in 2007. In between, Rimi engaged with other tendencies, the totality of which only subtracted from his political personality as far as it concerned tendency identity.

Alhaji Sule Lamido

As the only person of PRP background in power in any substantive sense by 2007, Sule Lamido acquired additional symbolism, both for those who were with him and those who were not. NEPU-PRP memorialisation dominated Lamido’s governorship, sometimes to the point that it was thought the PDP would query such as anti-party activity. It never happened but even then, such memorialisation did not transform into anything institutional in terms of rehabilitating the tendency. Without such an institutional umbrella, all cases of disagreement within the fold transformed into personal quarrel with Lamido as tendency leader or the main tendency man with political power by then. By the 2015 election, a large number of politicians in the Kano-Jigawa area who were PRP in mind had angrily migrated to the APC where they won elections to Kano and Jigawa state Houses of Assembly as well as the National legislature.

As a result of that and notwithstanding Lamido’s record accomplishment in infrastructural development as governor of Jigawa, the NEPU-PRP component of the PDP had become an empty shell by 2015. Lamido had adopted a rhetorical warfare against the Buhari struggle for the presidency. While it was principled of him to do since he had never allowed Buhari any inch, he was moving against something of a national mood that made him a lone wolf strategist. It was as if he knew something would give to make Nigerians start complaining against Buhari. That did not make it right for him to engage in a lone wolf strategy. But every other intervention was too late. Shortly after that, Lamido came face to face with being tried for alleged graft. That was, however, not a Buhari offensive. It was still PDP eating itself up. Whether the outcome of that process flattens him out completely or makes him even stronger, it is another example of the disasters the tendency has, historically, encountered at every turn since 1979, each of which further undermined a party with a great message in terms of emancipatory politics in a semi-industrial society in need of rapid transformation.

As things stand today, Rimi is gone. Balarabe Musa is still firing but he is not getting younger. Sule Lamido has his battles to fight. Ali Saad Birnin Kudu is not coming out aggressively for tendency leadership and new or younger leaders are not rising. Or, are they? Where might they be? Is there any chance for revivalism? How and with which variant of populism now? All these should be important questions at a time of deep divisions that only a party or a tendency raising a banner of hope across the divergent identities and interests in Nigeria can overcome. Best if such emanates from northern part of the country which history, identity politics and extreme poverty in all the three geopolitical basements have combined to turn into an experiment in anarchy and as to raise the question as to whether it is leadership or power the region is most in need of now.

As things stand today, Rimi is gone. Balarabe Musa is still firing but he is not getting younger. Sule Lamido has his battles to fight. Ali Saad Birnin Kudu is not coming out aggressively for tendency leadership and new or younger leaders are not rising. Or, are they? Where might they be? Is there any chance for revivalism? How and with which variant of populism now? All these should be important questions at a time of deep divisions that only a party or a tendency raising a banner of hope across the divergent identities and interests in Nigeria can overcome. Best if such emanates from northern part of the country which history, identity politics and extreme poverty in all the three geopolitical basements have combined to turn into an experiment in anarchy and as to raise the question as to whether it is leadership or power the region is most in need of now.