Is the Beaten Track Beaten?

In 1999, General Olusegun Obasanjo became the president of Nigeria against the background of a highly fragmented or a deeply divided country. June 12 politics made the relationship between the Abacha regime that preceded Obasanjo’s and the southwest particularly tense. Obasanjo ended up with very meagre votes in the region for reasons that had to do with regional reservations about how far Obasanjo would go regarding key demands for reform by the Yoruba nationality. So, he needed to innovate politically in other to achieve reconciliation. In constituting his cabinet, Obasanjo went for members of other political parties. The most notable remains the late Bola Ige who emerged as Minister of Justice after an initial stop in the Ministry of Mines and Power.

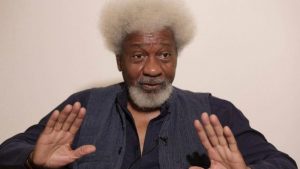

Wole Soyinka cried out for Culture in Buhari’s cabinet

In 2015, General Muhammadu Buhari walked into the Obasanjo shoes in 1999 but refused to follow that path. He got miserable votes in the south-south and the south east. That suggested he too was inheriting a fragmented polity and needed to embark on reconciliation. He balked. First of all, he did not even constitute a cabinet for about six months. While that lasted, speculations took over. So much so that when the cabinet eventually arrived, it was an anti-climax. But Nigerians welcomed the cabinet quietly, hoping that, somehow, something great could still come. It was only Wole Soyinka who expressed alarm how culture could be eliminated from the list of ministries. Promptly, Culture was added to Information to form the Ministry of Information and Culture.

Buhari took off without reconciliation

So, the Buhari regime took off without any concession to reconciliation. Without that, problems developed immediately, the stalemate widened subsequently. Key issues in question includes managing the economic recession, handling the contradictions of the anti-corruption war, coping with the complications of the counter-insurgency operations in the north east, the security challenges in two out of the three regions in the south as well as a vigorous campaign for restructuring, suggesting complete elite fragmentation.

Might Buhari regime have been paying a price for falling out of the beaten track? For, since 1999, no regime has successfully evaded offering one form of concession to reconciliation or another without paying a price. Yar’Adua who took over from Obasanjo in 2007 was so alarmed by details of the electoral ‘cuwa-cuwa’ in the conduct of 2007 election that, to Obasanjo’s embarrassment, he set up the Justice Uwais Electoral Reform Committee. It was an invitation to reconciliation following the outcry around the free and fair status of the election. That brought down the temperature somehow even though many of the recommendations were not implemented. Yar’Adua equally had some ministers from the All Nigeria People’s Party, (ANPP) who, however, ended up defecting into the PDP.

Dr Goodluck Jonathan, Yar’Adua’s successor, inherited and retained one of them who also defected to the PDP eventually. That was up to 2011. After his election in April 2011, he did not engage in any elaborate reconciliation in terms of an expanded cabinet. His concession did not go beyond setting up the Ahmed Lemu Panel into the April 2011 post election violence. It is doubtful if there was much implementation of the report. Both Dr Goodluck Jonathan and the PDP paid the price for that in 2015. The PDP is still paying the price for that defeat. It is losing organisational identity, suffering from an intractable rift. It would be interesting to see how the APC fares in 2019 without a major a re-conciliatory move.

Minus reconciliation, a stalemate from which there appears to be no clearly articulated pathway out has stood down the country. Everyone accepts the system is not working but not much is on offer. In the face of deep social decay and crisis, nothing bolder than a rehash of failed business models have surfaced. No group within the elite is bold enough to ask Buhari to step aside as Obasanjo could say in the case of Umaru Yar’Adua. Nor is any group there in a position to pose as a minimum to Buhari a safe landing mechanism such as in a Government of National Unity. Everyone expects the Vice-President to, somehow, assume full power and magically solve the problems. Well, Osinbajo attended one of the powerful colleges of the University of London. As the largest university in the world, it is possible he learnt magic wands there. But even if he did, Osinbajo is going to do no magic here without one model of reconciliation or the other. Not in the politically mined terrain he is stepping into, with cabals, godfathers and powerful individual republics within the republic already staging political reggae on Broadway. Some people say they are praying that in 2019, they would not be hearing nasty testimonials on him by the same crowd cheering now.

National ‘sai kai’ for Buhari as it was in Ogun State during the 2015 campaign

It is not as if Buhari dropped from the sky just like that. Everyone said ‘sai kai’ to him. Even when Sheikh Ahmad Gumi cautioned against Buhari and Goodluck Jonathan as candidates in 2015, he was speaking to a country already too drunk about Buhari to listen. Today, everyone is jumping up and down, posing as a hero for criticising Buhari. Does Nigeria appreciate the multi-dimensionality of the problem? Supposing Buhari surfaces and resumes duties before the stipulated three months limit he could be away? And supposing he does so without anything different about development strategy and reconciliation? What does the country do? Impeach him? Or, continue the current generation of hysteria which is not stopping his cabal from carrying-go? Tough luck!

A Government of National Unity has been the beaten track in terms of calming and reconciling the polity. Many believe now that it is a safe landing mechanism which acts as an interface between the president and Nigeria. This still holds even if Osinbajo is taking over since he would need shielding and a jump off point. It offers the country the possibility of diluting the bipartisan tension and a reconciled polity capable of privileging a ‘New Beginning’ at the expense of the impending rapturous power struggle. It responds to reconciliation. How, for instance, does anyone get IPOB off the track already ignited without incorporating the Igbo symbol today, whoever that could be? Perhaps, Nigeria, as usual, does appreciate the stalemate but still doing the Nigerian thing. What might that be? It is called the Nigerian thing because it eludes capture in how the cloud of trouble clears magically each time it gathers over Nigeria.