Global Media (Mis) Representation of Africa: Is Martin Scott Bursting a Myth or Inventing Another?

By Adagbo ONOJA

In the context of the fear that an African protestation of misrepresentation in the global public sphere is the next likely global conflict, Dr Martin Scott’s new academic paper might reverberate far beyond the academia and newsrooms. If the paper, “The Myth of Misrepresentation of Africa” does so, it would fundamentally be because it is challenging what has passed as nearly a self-evident truth that the Western dominated or controlled media industry has still to resolve how Africa and Africans might be constructed.

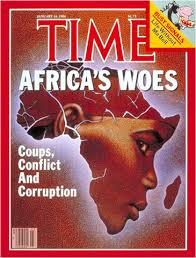

Africa has lost the ownership of her story as far as the story lines have been written, edited and pushed out from London, Paris and, recently, Atlanta, Doha and Beijing. This is what may be taken as the summary view on the issue, with scholars saying that much of what comes to the reading or viewing public about Africa bear allegiance to a racifying, negative or alarmist trajectory. Even in the post Cold War when internet has made some people to claim that Africa can now write back, newer and even more seductive evidence and interpretations have emerged to reinforce the misrepresentation argument. In 2014, Toussaint Nothias then at Leeds University in the United Kingdom, (now at Stanford University in the US) produced a particularly piercing argument to the effect that the self-reflexivity we see in such narrative as ‘Africa Rising’ does not mean that the summoning of Africa’s difference in the global media is no longer within what Jo Ellen Fair would call historically articulated power relations. Rather, he calls the trend discursive (re)inscription of Africa’s difference within the logic of neoliberal globalization.

Africa has lost the ownership of her story as far as the story lines have been written, edited and pushed out from London, Paris and, recently, Atlanta, Doha and Beijing. This is what may be taken as the summary view on the issue, with scholars saying that much of what comes to the reading or viewing public about Africa bear allegiance to a racifying, negative or alarmist trajectory. Even in the post Cold War when internet has made some people to claim that Africa can now write back, newer and even more seductive evidence and interpretations have emerged to reinforce the misrepresentation argument. In 2014, Toussaint Nothias then at Leeds University in the United Kingdom, (now at Stanford University in the US) produced a particularly piercing argument to the effect that the self-reflexivity we see in such narrative as ‘Africa Rising’ does not mean that the summoning of Africa’s difference in the global media is no longer within what Jo Ellen Fair would call historically articulated power relations. Rather, he calls the trend discursive (re)inscription of Africa’s difference within the logic of neoliberal globalization.

Nothias’ work remains interesting because it went beyond engagement with the text to interviewing the staff involved in the making of the symbols by which Africa is captured and presented, only to show how that process itself unmakes Africa because they are rarely about the continent but technological configurations. Still very interesting about the paper in question is its coverage. All the seven British, French and American magazines he focused on are also the staple of the Western elite circles whose action and inaction decide a lot of things across Africa.

It is this established ‘truth’ that Dr Scott has called to question by asserting in his just published academic paper that the claim of misrepresentation of the continent is a myth. The British media scholar who wrote a doctoral thesis that was passed without a single correction at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom says that what has sustained the claim of misrepresentation of Africa is not any evidence from actual representation of Africa but academic practice patterns as well as the vested interest of multinational corporations, governments, NGOs, and researchers. As such, he argues that the world still lacks the basis for that generalisation about the nature of how Africa is presented in the global media.

It is this established ‘truth’ that Dr Scott has called to question by asserting in his just published academic paper that the claim of misrepresentation of the continent is a myth. The British media scholar who wrote a doctoral thesis that was passed without a single correction at the University of East Anglia in the United Kingdom says that what has sustained the claim of misrepresentation of Africa is not any evidence from actual representation of Africa but academic practice patterns as well as the vested interest of multinational corporations, governments, NGOs, and researchers. As such, he argues that the world still lacks the basis for that generalisation about the nature of how Africa is presented in the global media.

Commencing the journey by taking down Nothias, Ellen Fair and a few other specialists on international media coverage of Africa, Scott levelled charges of selectivity in their choice of both the media and the African countries from which their works produced the conclusions they produced. And that such gaps matter because they typify the broader literature. The overarching image of Africa as a backward and violent terrain where warring tribes slug it out in a context of extreme poverty that is associated with Western media is not proved because those who did such studies did not base them on textual analysis of actual media discourse nor on more than a few countries, he points out, citing Ellen Fair’s paper which used media coverage of just South Africa and Liberia in her own study.

He is worried that the ‘myth’ is already defining how China reports Africa in the fashion of ‘Africa Rising’ or a tendency to emphasise what is considered positive by running away from wars, violence, poverty and corruption. That is aside from other journalistic manifestations of the ‘geopolitics of information’. Unsaid in that is a claim that publishing Africa positively is not a critique of media imperialism. Publishing Africa positively could equally be injurious by trying to hide tension and ruptures.

A critique of misrepresentation

Scott’s main ground, however, is the method by which the claim of misrepresentation is arrived at. It puts him at loggerhead with what he dubs as narrative literature review by which a researcher sums up the grounds covered by much of what previous researchers had done and then restates the puzzle still begging for attention. His quarrel is that this way of doing it conforms to no consistent or systematic pattern of evaluation beyond what is admissible by the cognitive make up of the researcher. He challenges its objectivity and comprehensiveness to be the guide to anything conclusive on how Africa is represented in the global media. Relying on Olatunji Ogunyemi’s conclusion in his 2011 work on representation of Africa online, Scott rests much of the conclusions scholars draw on the issue on what perspective underpins their scholarship. In here, he finds explanation for why coverage of a non-crisis oriented event as the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa, differences in the coverage of different parts of Africa or coverage of Rwanda genocide considered as sophisticated analysis besides the more dominant notion that coverage was denied or didn’t count.

Within this context, scoping review offers the approach he considers more appropriate “in order to map all new empirical analysis of US and UK media coverage of Africa between January 1990 and April 2014” (p. 193). What is involved in scoping review approach is what he describes as a systematic selection, collection and summarisation of existing knowledge in thematic areas. This way, it is able to locate concepts and theories that are key as well as sources of evidence and gaps. With explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria, this also gives the approach the comprehensiveness and objectivity that narrative review of literature is said to lack. So, based on English language journals, book chapters, conference papers and reports which relied on Content Analysis or Discourse Analysis, Scott set out to look at representation of Africa in newspapers, television, film, magazine, radio, the internet and textbooks but not art, music, poetry, literature and Museum exhibitions.

Nigeria’s geopolitically innocent state television

South Africa’s state television and its own problems as far as ownership of the African story is concerned

One key outcome is how studies of US and UK media coverage of Africa is on few African countries, notably South Africa, (the Apartheid transition especially), Rwanda, (much around the genocide), Sudan, (genocide and secession), Sierra Leone, Somalia and Kenya. Countries such as Nigeria, Niger, Madagascar, Tanzania, Botswana and Chad were not prominently in the news as at the time of the study. Similarly, North Africa and Francophone Africa are not covered much. The second key outcome is how just New York Times and The Guardian in the UK constitutes the Western or international media we are talking about. A few other media organisations write about Africa as much as these ones and those few include the Washington Post in the case of UK and The Times, The Telegraph and BBC Online, not the Mail or The Sun.

What internet usage can a continent without electricity reasonably talk about?

On the strength of these key findings, he argues that the pattern of representation must be Africa wide and beyond coverage concentrated on peak moments before we can claim that Africa is negatively represented. The crux of his analysis is that “Any attempt to advocate for alternative representations of Africa must surely first establish which media outlets represent which aspects of Africa or “Africa” in ways we might object to, and which do not”, (P.207). And that the finding that the evidence does not exist to support the claim of misrepresentation of Africa expose the rhetorical nature of the idea. For him, to claim that war, corruption and poverty dominate the headlines when Africa is being reported is a legitimating rhetorical strategy for the action implied by the claim. And he goes on to cite the corporate agenda behind such rhetorical strategy. Finally, he implicates academics or researchers in that strategy because, by drawing the conclusion of misrepresentation, they become linked to the actions implied through the discourse – power nexus.

This paper is just formally making its way into the market place of ideas although it has been published in some form in 2016. But it is now that it is fully published that the academic wrestling around it would begin. There is bound to be academic wrestling around it because he is challenging what has almost become a self-evident truth that Africa is mightily and historically misrepresented in the Western dominated global media. Better still, scholars and practitioners of the global media are confronted by that poser. It rests on the difficulty of getting Western thinkers who have much to say about Africa that would be considered positive from the point of view of the dominant racial and spatial images in those discourses, including those by some of the most brilliant and progressive Europeans and Socialists. As the media has been the more consolidated channel through which the West manifests its difficulty with otherness in the case of Africa, it has been the hub of Africanist protest scholarship and activism on this perceived historical mis representation.

Apart from the questions around methodology that would be raised, there is bound to be tough probes of some of the findings, with particular reference to the determination of whether or not Africa is (mis)represented. Scott pointed out, for example, that sophisticated analyses of Rwanda genocide in the media are not mentioned, leaving the majority to go with the impression that the global media was ‘silent’ and, therefore, implicated in the genocide. Would this ‘sophisticated analyses’ not even further implicate the global media in that whichever narrative of the genocide reigns, it has been constructed by the global media. First, it was the narrative of the genocide as a product of Hutu-Tutsi tribal hatred. Subsequently, snippets challenging such in favour of accumulation intrigues around mining rights in the Congo began to emerge.

Supposing one of the questions thrown at this study is whether methodology escapes the knowledge/power bind? Wouldn’t one myth have been destroyed in favour of another if generalising from a case study is no longer a way of probing a particular social problem? In other words, how might the universe of the global or international media be established? In Africa, the kind of media houses that Scott’s study isolated (New York Times, BBC, The Economist, Newsweek, Time, The Times) are the media associated with being alternative or parallel governments, not The Sun or the rural or neighbourhood press. So, which is which, conceptually? As a 2017 work, the critics might not have woken up to this yet. But it won’t be long in coming.

A London based African initiative

If and when it does, one thing it will drive home is this. Even in the age of the internet, the global media is still a factor in Africa. Its ‘silence’ is a problem as much as its reporting. It cannot be that everything that the global media reports is malevolent, racist or aimed at undoing Africa but that popular culture generally serve national interest or, as the phrase goes, writes the global space from the centre of power and authority. That is why nobody heard that the collapse of coffee price in the international market aggravated living conditions in Rwanda, predisposing people to the kind of horrendous violence that occurred. Instead of that, ancient tribal hatred was privileged without the context in which tribal privilege could become so deadly. Nobody heard of interests in mining rights being behind the production of Hotel Rwanda which is now being described as an excellent case of how decisive the media has become in the determination of victory in the post modern war. What Scott’s paper might have raised is the absence of any alternative to Africa’s (mis) representation but Africa’s own global media. Or they might keep killing themselves for reasons they can never find out till they finish each round!