Prof Ibrahim Bello-Kano

By Adagbo ONOJA

Nigeria is, indeed, at war. It is the kind of ‘war’ imagined in Eedris Abdulkareem’s musical number ‘Jaga Jaga’ and in which the society is decentred. The songster’s language for that is the oxymoron “Nigeria Jaga Jaga”, following which “everything scatter, scatter” and then the suffering of the poor man. It is understood that as the incumbent when the number was released in 2004, President Obasanjo was infuriated and vowed to wrestle the musician to the ground if he caught up with him. Eedris was bound to infuriate an Obasanjo who was scoring his government high on anti-corruption battles and promoting the claim of things getting better before that representation of Nigeria emerged from an artiste who was observing the dynamics from the popular side. Today, even Obasanjo has come to agree that Nigeria is Jaga Jaga and everything is, indeed, scattered. After all, Obasanjo said recently that the country has never been so fractionalised.

Nigeria is projected to be in the region of nearly 500 million in population before mid century and, therefore, the third most populous country in the world. That is something some other country would have started preparing for already. No. Not Nigeria. At the moment, it is even so decentred a society it cannot think properly about tomorrow. Not yet. Everywhere is war across Nigeria. There is Boko Haram war; Niger Delta Avengers’ war; Indigenous People of Biafra’s war; the herdsmen war on farmers. Others are the war of kidnappers/abductors/smugglers and hostage takers just as human/currency/drugs and arms traffickers have their own dimensions. And ritualists are waging a war on the society too. It is a totally Hobbesian setting and about which no one can be unconcerned in relation to why? Where has Nigeria found itself?

That is, however, a question whose answer does not reside in any one particular space. The answer can only come from whatever consensus emerges among discussants of the poser. The challenge is thus not one of getting the correct answer in itself but getting discussants capable of sustaining a grounded debate on the question. The selection below satisfies that requirement.

Professor Amaechi Nicholas Akwanya from the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, is not an academic lost in contemplation. He is actively involved beyond routine academia. He is of the clergy. It was the side of him one only got to know of after the interview with him was done with. It is remarkable that, in an interview that lasted well over an hour, his language use manifested that side of him only in two words – when he contrasted light with darkness in explaining a phenomenon. Otherwise, the religious sensibility never manifested in his analysis. What that means is that Prof Akwanya can be trusted as far as the mandate of knowledge goes. He is not part of those causing confusion on the campuses in Nigeria, confusing the mandate of knowledge with other mandates in an academic setting. A doctoral product of the National University of Ireland, the Professor of English and Literary Studies is the author of twelve books, over two dozen academic papers, of which the one titled “Chinua Achebe’s No Longer At Ease and the Question of Failed Expectations” would appear to, most directly, speak to the Nigerian crisis and, therefore, most appealing to the politicians. Note that reading Akwanya is also reading a onetime editor of Okike, another unique contribution to world literature from Nigeria.

Ibrahim Bello-Kano is the extraordinarily engaging Professor of English and European Languages at Bayero University, Kano. IBK, as he is more popularly known, is currently a member of the Editorial Board of the African Humanities Publication Series in conjunction with the American Council for Learned Societies and the University of South Africa Press. This takes the Visiting Professor at Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria and the veteran of many celebrated debates in the Kano –Zaria academic axis out of the country frequently to Ghana, Kenya, Tanzania and South Africa. Occasionally, he ends up in Australia, contesting grounds, depositing and fetching knowledge. The former visiting scholar at the University of Delaware in the late 1990s has remained engaged with Fredric Nietzsche, Matthew Arnold, and Jacques Derrida. IBK is the author of a forthcoming book, Travel, Narration, and the Fiction of Exploration from the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria Press.

Dr Yima Sen is a discussant of multiple entrapments. He remains an activist of the radical nationalist bent while also being a politician. And these are without any injuries to his commitment to academia, beautifully carrying on with teaching modules across Mass Communication and International Relations at Baze University, Abuja while working on the materialisation of an additional doctoral degree in Political Science. But, he is not retiring his PhD in Mass Communications from the University of Amsterdam. Yima has worked as a communications specialist in the UN system as well in the Presidency under the Shagari regime but as a public policy expert in the Obasanjo Presidency.

Edris Abdulkareem & Former President Obasanjo

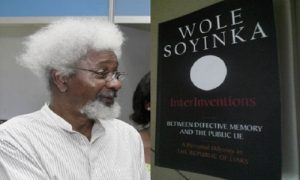

Professor Soyinka

A Powerful crust of the Christian establishment in Nigeria

The Sultan of Sokoto, a foremost custodian of religious and traditional values in Nigeria

Professor Ibrahim Bello-Kano:

Prof Ibrahim Bello-Kano

Prof, nearly a dozen type of wars are going on simultaneously across Nigeria today. Ritualists are doing their own thing just as Boko Haram is ever monstrous. There is IPOB there, Avengers, kidnappers, herdsmen and bandits. And the hostage takers are there too. So, all sorts of wars are going on around us. What do you call this moment? Tumult or a turning point for Nigeria?

Uhm, well! It is not a turning point. It is part of the increasing decay and the structural dysfunction, in the economy, in the cultural minds of the people and sectarian tendencies fuelled by all sorts of sectarian forces from religion to political to cultural relations. Also, if you want to give a material explanation, there are issues of rural poverty, lack of jobs, lack of infrastructure and lack of hope across the country, especially in the rural areas. And of course questions about lack of opportunities in general. Small businesses are folding up because they have to rely on electric power generated at personal cost. And this employs the largest number of young people in the country. And you have to look at the issue of religion in the churches, in the mosques. The state is utterly unable to calm all sorts of sectarian religious indoctrination. Around here, anybody can get on the radio and say anything. They could even ask why the government should build roads and not fortify the faith first. Now, there are young people whose primary philosophy is religion or religious thinking. And this is happening because religion has been left to private individuals. Anyone can become a “mallam”, anyone can become a pastor and establish a church. And, in the press also, you can see open sectarianism. I think you can see that the state as a structure, the state as a whole, is very weak – weakened by a number of things, from corruption to just basic lack of modernisation. And then, successive administrations have done not done any better in this area. You can see, beginning from the Obasanjo administration, for example, that relatively, policies are begun but then they quickly fizzle out, no impact. It is either inefficiency within the system killed the programmes or the money is stolen and or merely made to trickle down but through those who steal say, N100m and throw two or three million to their relatives or to a village or community and they become the instant heroes. And also the cultural mind problem. You know, many Nigerians, for example, have not had what you might roughly call the enlightenment values of reason, critique or enlightened self-interest. These values are far away from the basic cultural minds of many Nigerians, including people who are ministers. You have educated people who do not understand the basic, primary things. You hear a professor harking back to base religious sentiment here and there. So, we don’t have vigorously secular academic institutions that could move our society or communities to new enlightenment values or the ideals of rational critique. Modern societies have a plethora of urban and enlightenment institutions, from geographical societies to vanguardist cultural groups and so on that offer to citizens the modern values of progress, tolerance, cultural refinement and what some literary critics would call sweetness and light. In short, this country and its civil society need a radical modernity, a modern consciousness of what it means to be a citizen in a rapidly changing world. Today, the old certainties, let me use that expression, that gave people security in the Middle Ages are no longer enough.

Would you be surprised if they say this is an attack on religion?

It is not an attack on religion. No, it is simply the need to provide an alternative to sectarian feelings and thinking and mindset. So, for example, you need a rational debate about electric power supply, about safety in homes and so on. Let me give you a good example. You know, it has come to the level where when you listen to the radio station, there is a programme, a radio sermon every one hour or so but there is no programme devoted to say, first aid, how do you resuscitate people, how do you give basic medical information you find in all relatively modern societies such as how to help somebody with heart attack, how to stop bleeding, very basic things like that for survival, basic first care. How to drive safely, how to avoid over speeding, if you get into Europe or most of these places, the state does that – how to resist temptation of over speeding, need to obey traffic rules, about conserving power in your homes. No, there is none here. I think we are in a very chaotic world where people think they can go on in their old ways without the need to adjust to a modern society. Or even to create a modern society, to be inventive in basic aspects of life. As I see it from here in Kano and the neighboring northwest states, superstition has returned. People want magical thinking.

This basic modernisation thing, not in the mould of the old modernisation theory but in the mould of the French word modernite, this is not happening. Where is the dissatisfaction with what you have, the issue of improving yourself, the issue of progress? Onoja, believe me, there are many complex factors for this situation. You can come from a structuralist explanation about underdevelopment, about poor economy, about mono cultural economy, about dependence and our relative insignificance in the international order. You can come from all those arguments but I would also like to open up this culturalist argument that people ought to be dissatisfied with what they have and have a new state of mind, are willing to change, are inclined to experiment with new things that will improve their life. And this is being blocked by traditional ways of thinking, from religious to sectarian to cultural beliefs such as belief that your ethnic group is special, your ethnic group has a special destiny in the world. For example, the Yorubas call themselves a race which is very ridiculous.

It is more peculiar with the Yorubas in the Nigerian situation, especially after this or that meeting of Yoruba Elders or Yoruba leaders and they come out to use the word race. Are the Yorubas a race in the sense of the racialist categories which we know? Are they a race? If they are a race, is that a separate ethnic group and separate cultural mind within the Negroid or outside of it but neither Caucasians nor Mongoloids? Are the Yorubas quietly saying they are different from Igbos or the Hausa-Fulani or the Dagomba in Ghana? All those claims, I call them sectarian thinking, broadly. They are all systems that divide people. You think you could be alone in the world and help yourself alone and your progress depends on you alone without the progress of your nieghbour? All these beliefs that people have of a destiny to either rule other people, all these sectarianism are all there, part of the cultural mind problem. Finally on this, I think, for me, I think the country is simply regressing to between 17th, 16th and 15th centuries. Or even to the 14th century. I said this because there are many people who openly say here in the north that we should go back to the past. And I call that going back to the Middle Ages. So, if people say this now, do they bother about confronting the challenge of modernite? That is modernity, not in the sense in which Rostow used it but the challenges of progress, of expansion, of electricity, water supply, sanitation, health, education, infrastructure, roads as you grow as a country. This is what all modern countries aspire to. Even within Africa, you find this. For example, I was in Tanzania, I found their university there, University of Dar es Salaam a little more modern than all our universities in terms of their attitude, their mindset, the way they organise seminar and even in the matter of external examiners. For example, they can invite an external examiner from Britain, from the US. Here, no, you must go to ABU, you go to Maiduguri. We are afraid of what is foreign, what is unfamiliar, what is unknown. We are not adventurous. We are a tamed people. We are afraid of the future. We want to stick to the present. In fact, some of the people want us to go back to the past, 500, 1000, 2000 years ago. Yea, you hear such voices in the western world but they are a tiny minority with no impact whatsoever. But, here, some religious people, political leaders and business elements say it all the time. And these are the very people who rule. I don’t want to use this word but I have to use it. I assure you this is a Bongo – bongo land. It is really a chaotic, terrible country. Everything is upside down. The leaders are just cynical. It forces you to recall Achebe’s Man of the People. So, the cultural mind of the typical Nigerian is a challenge for all of us, academics and so on.

Now, that is your repertoire of the moment. But some people would say it is the political leadership that has the problem is. Others would say no, it is prolonged military rule. Yet others would swear it is our diversity and there are those who would say it is external conspiracy. To which of these or in which order would you like to arrange these?

To me, none of them explains our situation. For example, if you talk about external conspiracy, who is asking you not to be what you should be? I find it unconvincing. It cannot be argued. Our diversity should be our strength. In most countries, diversity is the reality. If you go to most countries now, there are significant minorities. Most Western countries now have diversity to the chagrin of promoters of traditional hegemony. About political leaders, no because they come from the communities. They have their own share of the problem but if you look at even the highly educated people, professors and the intelligentsia, we say, what is the difference between them and the political leaders? Look at Soyinka, for example. One day, he pursues a progressive agenda and the next day, he pursues a reactionary one. He is not consistent. So, again, the political leadership critique doesn’t fly.

So, there are the structural constraints, I know, issues of the nature of capitalism we are running, our insignificance in the global economy, our dependency on this oil thing which fluctuates but, also, look at our own inherited tradition, look at our attitudes and look at the way we do things. Look at our fear of change, our abiding fear of experimentation. We are largely very conservative. We are traditional people in the best sense of the word. We have not been lucky to have a Castro in Cuba, for example, or Singapore or the leaders in some parts of South East Asia like Malaysia. We didn’t have that, largely because of the ethnic divisions but diversity shouldn’t be our problems at all. Most countries in the modern world are ethnically diverse. They are some of the most interesting countries in the world. So, it is the continuing hold of backward ideas and values plus sectarian promotions by politicians and religious people in the churches and mosques that goes on to produce a mentalite, (mentality regime) hostile to even progress, progress in the sense of borrowing from the best possible sources to improve your situation. I am not being dogmatic about this but I think we have simply failed to modernize. If you put everything together, we are now undoing ourselves by our secret desire to go back to the past. A desire by which we justify everything. The outcome is that, in this country, you could find ten mosques and perhaps more churches on one street, each with a loud speaker. Is that how to develop?

The overarching context we are operating is the global one or what they call globalisation. You don’t seem to have any connection between that equally powerful force and the current confusion Nigeria is experiencing.

Yea, you are right because we are at the receiving end of the world system and all that. Certainly, this is a key issue. We are now desperately looking for ways out of recession. And there is the cultural side of globalisation in terms of the messages received. Some of the messages appeal to young people in ways that are not benign. Such messages are capable of all sorts of interpretations and misinterpretations about what to duplicate here and what not to. When you look at facebook, Whats’upp and all of them, this is what strikes you. And many young people have access to these materials. If you put all these together, these things define our situation. Yea, but even then, if you go to Ethiopia now, do you think you will find exactly the kind of cultural mindset on display broadly across Nigeria?