So prone to breakdown of consensus that, more than many other countries, Nigeria needs a national cohort. Yet a successor set is nowhere in sight, certainly not one with the relative coherence of the set making its slow but steady exit, with all its members 70 years old and above. Isn’t that the making of a dangerous vacuum or might a cohort already exist in the political incubator, merely waiting to come to its own by the next breakdown of consensus? Intervention takes IBB’s 75th birthday as a cue in to look at the issue.

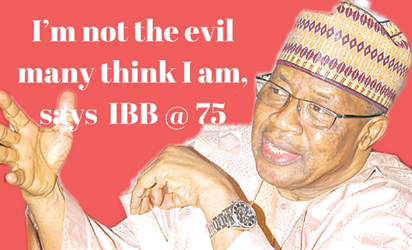

Ibrahim Badamasi Babangida, aka IBB who ruled Nigeria as a military president from 1985 to 1993 was 75 years old last week and hell was let loose in claims of his significance. The goodwill messages were simply speaking to the concept of power in that someone, rightly or wrongly, seen as the devil incarnate would amass the claims of his significance contained in the messages, including the goodwill message from the incumbent president with whom the relationship has not been very good. It goes beyond the cultural convention of goodwill to a celebrant into the realm of an imperative to represent IBB positively as the beginning of wisdom in the power game in Nigeria. Heady journalists with nothing at stake can throw all the irreverent adjectives at him but not those in the thick of the business of acquiring state power. Read Buhari, Atiku and Bukola Saraki’s messages again and see if this is not borne out by the pragmatics.

A web picture of some members of the outgoing cohort

Not surprisingly, it came to happen that no one mentioned that which ought to have been bogging people’s mind each time any of the Mohicans – Gowon, Obasanjo, T. Y Danjuma, Muhammadu Buhari, IBB and Abdulsalami Abubakar– celebrates his birthday now. None of them is less than 70 years old. By the natural order of things, every birthday anniversary brings each one of them close to the great departure. Yet, these are the remaining members of the cohort that has run Nigeria since 1966. And the prospects of their exit without a successor cabal, ‘guardian angels’ or generation in sight ought to be worth national reflection vis-a-vis the future of Nigeria.

IBB himself did not help matters. Always obsessed with his place in history, he was more interested in using the occasion to refute the image of the ‘evil genius’ that he has. What a needless worry! There will never be one history for all time as for anybody to worry himself about what his or her place in it would be. History, like beauty, will always be in the eye of the beholder because we all experience history differently. The historical account on offer today might also not be the one on offer in another two decades hence. Every historical account is, ultimately, a product of power. Concern with his place in history should have been directed at the power/knowledge dynamics and how it works.

Of course, both IBB and the other members of the outgoing cohort will hardly ever overcome the sense of failure associated with not being able to transform the country from an agrarian to an industrial economy. Except Gowon who was entangled in prosecuting a war and Abdulsalami whose tenure was so brief, all the others, particularly IBB and Obasanjo, must be wondering how it happened that, unlike other military dictators in say Brazil, Korea and even Indonesia, they accomplished nothing near social transformation of Nigeria. In fact, to use a memorable rendition of that failure by Professor Isawa Elaigwu in an interview with this paper last week, (www.intervention.ng), “The military came in as political physicians but ended up as political patients requiring even greater dosages of the medicinal prescription they had come in to serve to politicians”. But, as Elaigwu also argues, the dialectics of military intervention in Nigerian politics is that while they failed to transform the country, the country might have since disintegrated without them.

The Gowons, the Obasanjos, the Danjumas, the IBBs and a whole layer of key military and non-military actors in that generation who found unity and coherence in having all fought in the Nigerian Civil War became the signifiers of the military as far as the legacy is concerned. These are the few who came to acquire the referentiality for the military’s role in keeping the country together, of ensuring that the centre holds even when things fall apart or threaten to fall apart. Almost all of them would come out badly bruised if put under thorough scrutiny in relation to accountability but there is none of them who has given anyone a listening ear when it comes to breaking Nigeria. In spite of intra-group quarrels and schisms, Nigeria, for them, is not negotiable. Their greatest achievement is thus that, with them, the question of divisibility of Nigeria is out. They are coherent on this to the point of providing leadership for the broader ruling class on maintaining the Nigerian system. And this they have done since 1966. They would encircle anyone who tried to do that by their incredible domestic and global networking.

Now, this cohort is on its way out. It is doubtful if they can still install the next president. The institutions they didn’t build, the successors they failed to groom and the quantitative rather than qualitative approach to development they favoured as leaders are all combining to weaken their individual and collective moral authority. Secondly, the Buhari political personality which would have restored to the cohort the moral authority to pull the strings from behind is being stressed out by a combination of factors. Meanwhile, there is none of them below the age of 70. Who and which interests constitute the successor national cohort for Nigeria?

The national cohort as a defining feature of national life in modern times is perhaps the most difficult reality to accept. The world must have thought that the idea of ‘guardian angels’ died with the French Revolution and the demise of the monarchy. Unlike old Roger, the theory and practice of guardian angels is not dead and gone to its grave. Instead, it is even more alive and everywhere else across the world. Paradoxically, the United States of America whose founding fathers sought freedom and equality of all that only a ‘new world’ could provide still offers the most brilliant case study in the politics of national cohorts, if we go by the testimony of the late Professor Peter Gowan. Gowan is the British scholar who coined the phrase ‘business democrats’ in 2004 to describe the members of what Dwight Eisenhower, American President called the Military – Industrial Complex, (MIC) in his farewell address in 1961.

(R-L) Gowon, Obasanjo & IBB just being human

Probably still lost in the ideals of the French Revolution, Eisenhower asked Americans to watch the MIC, now also referred to as the Military – Industrial – Media – Entertainment Complex, (MIMEC). He was mistaken. For, as Peter Gowan argued his concept of ‘business democrats’, they have so successfully convinced everyone else that only free enterprise can serve the American essence and this to a level that makes an alternative look like an absurdity. In other words, they have provided a binding national narrative that, like all such successful discourses, makes a nation, notwithstanding the misplaced power Eisenhower feared about it. So, Gowan calls the national cohort in the US a very brilliant and successful one from the point of view of ruling class politics. Bernie Sanders might have questioned this claim but how far is he going? Given what the US symbolises in liberal democracy, it must be something that it also has a national cohort.

Nigeria has remained a baby of the national cohort. It was brought into being by the colonial cohort: the British colonialists, a perfect example of a cohort. It was this cohort which solely, either for its own strategic reasons or for reasons imposed on it by the contradictions of colonial warfare, created Nigeria. Their sole authorship of Nigeria is now being cleverly used by those with reservations against the Nigerian state as presently constituted, by saying that Nigerians were not consulted as if there is any nation whose citizens were so consulted before the birth of the nation. The history of state formation lacks evidence of any such consultation, even in the most recent cases such as Finland, Poland, Pakistan, Bangladesh and South Sudan. In history, the creation of the citizens follows the creation of the state, not the other way round. As it has turned out, whatever reasons actually impelled the British to create Nigeria, the country is today British imperialism’s greatest gift to the Black world by being the largest number of Blacks under one government in human history. Whether the Nigerian elite can still give effect to this gift to the Black world is a different matter.

Somehow, the country has not been able to fly. It has not been a success story in managing itself. Even now, it is savouring another moment of self-doubt in a very banal debate on restructuring. So prone to such distractions or breakdown of consensus that the national cohort becomes a major requirement for stability in Nigeria. But, where are those elements today below the age of 70 in whose hands as a collectivity Nigeria might be most safe? This question is important in the sense that there are some people in Nigeria who, without meaning it, can ruin the country if there isn’t a cohort that can overwrite its acts of thoughtlessness, arising from shallow internalisation of statecraft. Several factors explain the reality of Nigerians untutored in management of power.

Unlike in those days, there are now graduates in the country for whom the university was not also an induction programme in Nigerianism. In other words, there are too many graduates in Nigeria now for whom the university was not a meeting point with fellow citizens from every other parts of the country because, in many of the new universities, majority of the students come from one sect within a faith or from just the owner state or such a small identity that practical lessons in diversity elude them. Secondly, Nigeria no longer has elite or finishing schools that groom students in leadership alongside academics. Third, what have existed as political parties have no party schools for the political education of cadres. Fourth, the banning of the old breed politicians by the IBB administration has meant elimination of two successive generations of leaders and the taking over of power by the one behind them without appropriate preparation or mentoring. One implication of that, argues some analysts, is impaired institutional memory. So, many members of the power elite now are completely overwhelmed or intimidated by the political offices in the land. Finally, the social media and its impacts on the reading culture today is held to have worsened political illiteracy. Many people would simply not read anything beyond a page nowadays. For these reasons, Nigeria needs a national cohort.

Such that as the American cohort did when George W Bush was leading the country into the bush (they brought in a melted tri-continental Obama) or as the outgoing cohort did when Goodluck Jonathan was clearly leading Nigeria into bad luck, (they brought a Buhari at last), the country would not be at risk from its own chief servants. However, from where might the next national cohort emerge? In particular, how might a national cohort in the sense in which we have known it in Nigeria emerge now?

The national cohort in Nigeria has ever been a solidly homogenous group such as the outgoing retired military players. The first cohort was the British imperial elite actors working in tandem with London. It was a homogenous cohort, from skin color to language to the core agenda – colonial warfare. The second set – those we came to know as the Super Permanent Secretaries – was no less homogenous in terms of professional orientation even as they came from different parts of the country. They collectively provided the technocratic underpinning for the military elite in the difficult days of 1966 to 1975 until the military began to feel uncomfortable with or jealous of their cohort status. And the military then dealt with that cohort in a way that some people believe is still affecting the system. That is a reference to the purge under the Murtala/Obasanjo regime in 1975. By then, this cohort had played the role of preserving Nigeria, a classic illustration of such being the story of how Justice Mohammed Bello successfully disarmed Murtala Mohammed from implementing his junta impulse in 1966 as told in Ayo Opadokun’s biography of the late M.D Yusuf titled Aristocratic Rebel. The third generation cohort is the outgoing set.

Some people would say that this is not a problem because a national cohort is not a club with fixed, objective criteria of formal membership. Most would agree that what most constitutes a national cohort is a clear narrative of the country. The outgoing one has a national narrative. That is what you hear when Obasanjo, for example, says he would feel diminished to have to introduce himself as a citizen of anything lesser than Nigeria as presently constituted. For him, it can be bigger but not lesser, meaning that if your agenda is anything about fragmenting what exists, he is not with you and you can only have your way if you overwhelm him. The same sentiments Danjuma manifested when someone made the mistake of suggesting something about the north-east going it alone at a regional meeting some two years ago. Or what Buhari means by saying Nigeria is not negotiable. He could not have meant that some restructuring is not possible in the course of the journey but not manufacturing another nation out of Nigeria.

So, which core group in Nigeria now has a notion of Nigeria that fascinates almost everyone else? The survey result shows Zero! That’s the most frightening evidence that Nigeria is in trouble. Does it then mean that the country is done for? Yes and no. No, because there are certainly very nationalistic and patriotic groups in existence across the country. No, because it is not the existence of such groups that is the issue but such groups that have emerged to push very clear positions about the future. There is a third position which says that even the outgoing cohort did not exist self-consciously before the challenges they encountered and from which they developed a certain notion of Nigeria. The assumption here is that there will always arise as a core, put their foot down and predominate over the forces of disintegration. It is the illustration of this claim that would form part two of this special report.

Some of the super perm secs of those days