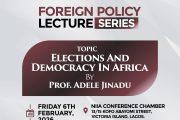

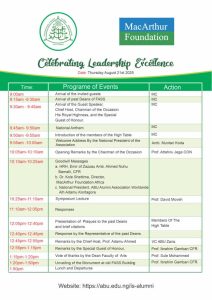

Published below is the full text of the Lecture at the maiden edition of a symposium to honour the former Deans of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS), Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. Organized by the International Studies Alumni Association, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria in partnership with MacArthur Foundation Africa, the event took place on August 21st, 2025, at the Center of Excellence, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. Although the lecture could in itself have been publishable, Intervention is doing so for the additional reason of correcting some bits of wrong details in its earlier story on the event. The story is left intact as an adjunct to the text. The author is of the Department of Political Science and International Studies, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria.

By Prof. David O. MOVEH

The author

Introduction

Mr. Chairman, distinguished Guests, ladies and gentlemen, I feel honored to have been invited to speak at this event even at very short notice; because, I was not a student in the old FASS; and certainly, I was not a member of the faculty. As a matter of fact, in the mid 1980s when FASS was still a crucible of intellectual activism in Nigeria, I was a pupil at the ABU staff school just outside this venue. Even though I was too young to comprehend the academic activities and intellectual activism going on in the faculty at the time, I still vividly remember the intellectually charged atmosphere; when after school, I visit my dad (in his office) who was secretary to Prof. A.D Yahaya; the Dean of FASS at the time. So, I appreciate the organisers of this event for the opportunity to serve as guest speaker for this event.

For over three decades, the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS) at Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, exemplified the ideal of the university as a site of critical academic excellence and a driver of national progress. The faculty represented much more than an academic unit; it was a crucible of intellectual activism, social consciousness, and political engagement. As one of the African continent’s leading intellectual centers, FASS nurtured a generation of thinkers, policymakers, and activists who helped shape political discourse and development paradigms in post-colonial Africa. International in character and orientation, FASS had scholars from almost everywhere: Americans, British, French, other Africans, and also Nigerians from virtually every state of the Federation. Ideologically, the Faculty tended generally towards the “left”; albeit with a fine diversity that reflected the disciplinary traditions and orientations of the scholars. Indeed, with a very vocal and politically conscious student body FASS represented a center of academic excellence where research and debates on national and international issues reverberated both nationally and internationally.

Today, after almost 30 years since the splitting of the faculty into 2 (the Faculty of Arts and the Faculty of Social Sciences), the intellectual activism and excellence that FASS was known for has declined in the succeeding faculties. Yet, the contradictions and crises that nurtured the academic climate within the former FASS have endured. Today’s occasion; in which the former Deans of the Faculty are being honored offers an excellent opportunity to reminisce and reflect: What was the nature of the intellectual activism and academic excellence FASS was known for; and what were its implications for politics and development on the African continent as a whole? What accounts for the apparent decline in the intellectual activism and excellence and what options do we as “progenies” of the academic firebrand that was FASS have in the quest to rescue Nigeria and Africa as whole from intellectual, socio-economic and political domination by foreign interests and their domestic collaborators? As we reflect on these issues, I shall attempt to revisit some of the most profound episodes of the academic excellence associated with FASS. Notable among these episodes are: the decolonization of the history of Nigeria and west Africa in general as pioneered by the critically acclaimed Zaria school of history, the Pan-Africanist movement initiated by Okello Oculi’s mock summit presentations of the Organisation for African Unity (OAU) and the intellectually stimulating debate on the “crisis of the Nigerian Economy” by Dr. Yusufu Bala Usman and Dr. Yusuf Bangura.

Prof Jega and Prof Ahmed Modibbo, a former Dean of FASS

The Zaria School of History: Methodological Innovations and Provocative Seminar Presentations

The Zaria School of History, nurtured within the FASS at ABU, Zaria, stands as one of Africa’s most influential intellectual traditions in historical scholarship. Emerging in the early 1960s at a time when African nations were regaining political independence, the school sought to dismantle colonial narratives and reconstruct African history from an Afrocentric perspective. Pioneered by Professor Abdullahi Smith and later championed by Dr. Yusufu Bala Usman, the Zaria school became a powerful academic force; both in methodological innovation and in shaping political thought across the continent. Prior to its emergence, the teaching of history in African universities, including ABU, largely reflected Eurocentric biases. Colonial historiography denied Africa a meaningful historical process, portraying the continent as “unhistorical” and “barbaric”; echoing the prejudices of philosophers like Hegel. Courses in the Department of history were taught mostly by European expatriates, whose interpretations ignored African oral traditions, archaeological findings, and indigenous records. The turning point came with the invitation of Professor Abdullahi Smith by the Premier of Northern Nigeria to document the region’s history under the Northern Nigerian History Research Scheme (NHRS). This initiative, embedded within ABU’s Department of History, provided the foundation for a new school of thought -one committed to challenging colonial distortions and training African historians to tell their own stories.

The Zaria School of History’s central mission was the decolonisation of African history. The school generally advanced the idea that political independence was incomplete without intellectual liberation. Thus, it developed and professionalised a critical historical methodology that is solely built on a thorough interrogation of sources with a view to writing an ‘objective’ history. The key features of the methodology adopted by the school in re-inventing African historiography; which set it apart from colonial epistemologies was that it:

- Treated oral sources as equally valuable as written records, subjecting both to rigorous critical eva

- Incorporated archaeological evidence, comparative linguistics, and ethnographic studies into historical reconstructi

- Questioned the reliability and embedded biases of colonial sources, even those widely revered in Western academia.

In line with the foregoing, Bala Usman’s seminal work entitled, ‘The Critical Evaluation of Primary Sources: Henrich Barth in Katsina, 1851-1854’ became an important “source criticism mechanism” that would aid historians that are willing to use oral sources in their historical reconstructions. As Alkssum noted:

Bala Usman called for the extension of the rigour employed in the assessment of oral sources to written sources. This was absolutely necessary because European written records obtained from travelers, traders, missionaries, companies, governments and their agents, which were the most widely used sources for the reconstruction of African history in the past five hundred years, were only assessed on the basis of their reliability and accuracy, not the world views ingrained in them. He pointed out that these written sources influenced students and researchers, who started their research work by first of all reading them at the Archives, or in published books and journals, before embarking on field trips to collect oral and other data. Consequently, the world views of the authors of these European written sources influenced the researchers even in terms of the questions they asked during field work.

Thus, while Barth was praised by European historians as “a meticulously accurate explorer of Africa”, Usman exposed inconsistencies and cultural biases, demonstrating the need to interrogate even the most celebrated written sources. Other seminal works which established the methodological innovation of the Zaria school of history includes: The Problem of Categories in the Study of the History of Central Sudan: A Critique of M. G. Smith and Others, still by Dr Bala Usman, and the 1979 PhD thesis of his student – Mahmoud Modibo Tukur; titled: “The Imposition of British Colonial Domination on the Sokoto Caliphate, Borno, and Neighbouring States (1897-1914): A Reinterpretation of Colonial Sources.” Tukur’s work focused on challenging colonial narratives and highlighting the agency of Africans in shaping their own history; and Bala Usman himself described it as a “densely detailed and interpretively nuanced study that lays bare the very foundations of the colonial state in what is now northern Nigeria”.

Apart from pioneering a more objective methodological approach, the Zaria school was also renowned for the assessment and critique of both national and international policies that have serious impacts on peoples’ lives. For instance, the school hosted many provocative seminar series on issues dealing with decolonisation in Africa, the role of western countries in perpetuating neo-colonialism, as well as corruption in government. Public lectures linking the university and larger community were also organised to enlighten them of their individual and collective responsibilities as Nigerians. In March, 1983, Marx and Africa Conference was anchored by the A.B.U School of History. Scholars, especially Marxists came from far and near to make presentations on the socio- political and economic conditions of the African continent. Some of these scholars include; Bala Usman, Patrick Wilmot, Bjorn Beckman, Claude Ake, Abdul Raufu Mustapha, Yusuf Bangura, Jibrin Ibrahim and many others. Indeed, part of the major effort of the Zaria school in the decolonisation campaign was in dismantling the forces of neo-colonialism enunciated in the operations and policies enacted by the so-called multi-national corporations and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) whose ‘stranglehold’ on Nigeria and Africa in general; unfortunately, continues even up till today.

In summary, the academic excellence and intellectual activism exhibited by the Zaria School of History include:

In summary, the academic excellence and intellectual activism exhibited by the Zaria School of History include:

- Challenging colonial distortions by refuting claims that Africa lacked history or civilization before European contact

- Advancing methodological pluralism through the validation of oral traditions alongside written records and incorporating interdisciplinary evidence.

- Linking scholarship to liberation by engaging directly with political and social movements for African self-determination

- Training generations of African historians; Many of whom went on to influence historical studies across Africa.

Through its work, the school became part of a broader intellectual movement (alongside the Ibadan, Makerere, and Dar es Salaam schools) that redefined African historiography in the second half of the 20th century. By dismantling colonial epistemologies and promoting methodological rigor, it offered Africa not just a reclaimed history but also the intellectual tools for navigating its future. Today, its legacy endures in African universities, research centers, and the continued insistence that African history be written by Africans, for Africans, and from an African perspective.

The OAU Mock Summit Presentations: A Pan-African Pedagogical Experiment

In the late 1970s, Prof. Okello Oculi a foremost Pan-Africanist pioneered mock summits of the Organisation for Africa Unity (OAU) as part of his undergraduate course on public administration at FASS, ABU. The mock summits required students to represent the policy positions of African countries, prepare governmental position papers, and debate topical issues on African development. The students mimic the speeches of Heads of States in continental conference settings. Yet, the initiative was not just about dramatization. It represented an innovative training in leadership, policy-making and public speaking -a “pedagogical experiment” which contributed significantly in promoting Pan-Africanist consciousness amongst the students and the university community in general. Indeed, as Bangura noted in his recent eulogy in honor of late Prof. Okello: “it could be argued that the biggest contribution of the mock summit at FASS, ABU was the incentive it provided to students to study at least one African country other than Nigeria”. The mock summit exposed and engaged students with specific continental themes that reflected Africa’s realities. Some of these themes include the liberation struggles and decolonization, the debates on African unity vs sovereignty, African economic self-reliance as espoused in the Lagos plan of action, etc. Despite ideological skepticism; especially in the 1980s when the OAU itself appeared to have lost its foundational optimism, Prof. Oculi insisted that nurturing Pan-Africanist values in youths could revive those lofty ideals. Even as the military establishment in the 80s scrutinized and tried to clip the initiative which was gaining national and international attention, Okello persisted in carrying forward the vision and replicating models of the OAU mock summits in secondary schools after leaving ABU.

By engaging students in weighty continental questions, Prof. Oculi turned classrooms into miniature Addis Ababa. Participants did not just memorize facts; they lived the dilemmas of African political leadership. The mock summit ensured that students studied the history, politics, and economy of their assigned countries and that they learned public speaking, negotiation, and diplomacy. It further inculcated the skill of critical thinking amongst the students by the juxtaposition of ideology against pragmatism, unity against sovereignty, and culture against modernity. Indeed, the result was a Pan-African intellectual rehearsal space; a safe environment where young Africans could imagine alternative socio-economic and political ideals for the African continent.

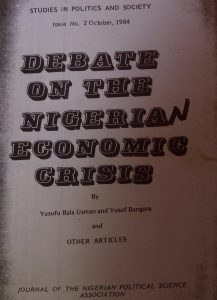

The Usman/Bangura Debate on Nigeria’s Economic Crisis: Radical Nationalism and Class-Conscious Socialism in Post-Colonial Nigeria.

The early 1980s marked a period of deep economic turmoil in Nigeria. Amidst this crisis, two intellectual heavyweights in the former FASS: historian, Dr. Yusufu Bala Usman and political economist, Dr. Yusuf Bangura engaged in a heated debate over its causes and remedies. Their exchange, unfolding between 1984 and 1985, remains a defining moment in Nigerian scholarship and public policy discourse. The genesis of the Usman/Bangura debate on the crisis of the Nigerian economy can be traced to the January 1984 lecture presentation of Dr Bala Usman on the topic: “Middlemen, Consultants, Contractors and Solutions to the Current Economic Crisis” at the University of Ife. Usman diagnosed Nigeria’s malaise as the product of a comprador elite -what he branded “contractocracy”– that siphoned wealth to Western capitals. He also challenged conventional politics and economic arrangements, describing them as illusory, clientelist, and treacherous to the nation’s integrity and sovereignty. As a solution, he proposed building a self-reliant capitalist economy -serving as a stepping stone toward a socialist Nigeria. His view extended beyond economics into systemic overhaul: representative politics were discarded as ethnic posturing, while civilian rule, he contended, offered no real freedom or democracy.

Three months later, at a conference of the Nigerian Political Science Association Dr. Yusuf Bangura presented a paper on the topic: “Overcoming the Basic Misconceptions of the Nigerian Economic Crisis”, which scrutinized the theoretical underpinnings of Nigeria’s economic discourse. While sharing Usman’s frustration with dominant narratives, Bangura critiqued what he perceived as Usman’s insufficient theoretical grounding. He argued that the Nigerian crisis must be understood within the broader capitalist world economy and class struggles, not merely through nationalistic or technocratic frameworks. Bangura urged that solutions should focus on empowering working-class struggles including: workers facing retrenchment, insecurity, and oppressive laws as the foundation for a socialist alternative to recurring capitalist crises.

In the following months the debate quickly escalated into a war of words over at least 4 rejoinders. Yet, even after forty years, the Usman/Bangura debate remains a subject of analysis for its bold interrogation of capitalism, imperialism, and national development. The debate juxtaposed Usman’s impassioned critique of neo-colonial economic structures against Bangura’s insistence on rigorous class-based and theoretical analysis. It exemplified the struggle between radical nationalism and class-conscious socialism in post-colonial Nigeria’s economic conversation. Indeed, the debate represented a watershed moment in Nigeria’s intellectual history and the discourse continues to offer vital insights into today’s struggles for economic justice, sovereignty, and ideological clarity in Nigeria.

In the following months the debate quickly escalated into a war of words over at least 4 rejoinders. Yet, even after forty years, the Usman/Bangura debate remains a subject of analysis for its bold interrogation of capitalism, imperialism, and national development. The debate juxtaposed Usman’s impassioned critique of neo-colonial economic structures against Bangura’s insistence on rigorous class-based and theoretical analysis. It exemplified the struggle between radical nationalism and class-conscious socialism in post-colonial Nigeria’s economic conversation. Indeed, the debate represented a watershed moment in Nigeria’s intellectual history and the discourse continues to offer vital insights into today’s struggles for economic justice, sovereignty, and ideological clarity in Nigeria.

The “FASS Model” and African Development

There is a strong correlation between the quality of academic training and the quality of political leadership in Africa. Many of Africa’s foremost nationalist leaders -from Kwame Nkrumah and Nnamdi Azikiwe to Julius Nyerere -were products of rigorous academic cultures that emphasized ethical reasoning, historical awareness, and policy competence. Within the tradition of FASS, academic excellence was never viewed as an end in itself but as a means to political enlightenment and ethical governance. The faculty cultivated leaders who understood the complexity of African societies and were committed to inclusive, participatory governance. However, the systematic erosion of academic institutions in Nigeria due to underfunding, brain drain, and politicization of universities has not only weakened the base of political leadership; but also, the capacity of intellectuals to provide the much-needed enlightenment. The result has been a proliferation of technocrats and politicians with limited historical and ethical depth.

African academic excellence as exhibited in the old FASS has far-reaching implications for development. First, it enhances the quality of research and evidence-based policymaking -a critical need for economies plagued by data gaps and donor-driven agendas. Second, it strengthens the local capacity to innovate in critical sectors of the society such as agriculture, healthcare, education, and technology. Drawing from the “FASS model”, the development of Nigeria and Africa in general should not be imported or imposed unwholesomely; but nurtured domestically and contextually through rigorous, localized research. Moreover, FASS demonstrated the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration, bridging the gap between politics, economics, culture, and history in crafting development policy. Today, many African universities operate in silos, losing the integrative strength that characterized FASS’s approach. Indeed, by next year- 2026, it will be 30 years that FASS was broken into two; and the impact of splitting the faculty into two may at best be described as mixed. While it may have encouraged specialization in the various disciplines, it has also encouraged tendencies of a “silo mentality” –where students and scholars alike exhibit deficiencies in multidisciplinary perspectives and approaches that the generation of scholars and students in the old FASS were renowned for.

Conclusion: A Call for Revival

While the legacy of FASS remains, its intellectual vigor has diminished due to systemic and institutional challenges which are not unconnected to the broader systemic failures of the Nigerian state. The decline in the funding of education, the commodification of education, and loss of academic autonomy has weakened the culture of research; and this poses serious threats to Nigeria’s development. To reclaim the academic excellence FASS was known for all stakeholders (the government, development partners, alumni and the university management) must prioritize investment in research, faculty development, and the protection of academic freedom. The old FASS showed that when scholars engage with society meaningfully, they can drive political change and development. We need a revival of that intellectual spirit, not just in ABU but also across the continent.

End of the lecture here

ABU, Zaria Honours Past Deans of FASS, Hits Nostalgic Button

The Nigerian university system came under a reflexive scrutiny today at the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria where deans of the old Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS) were called to be honoured. Attracting a cream of the society – the Zaria Emirate traditional authority, the university Vice-Chancellor and the MacArthur Foundation which supported the memorialisation – the occasion turned into a nostalgic soul-searching bordering on an unspoken case for a return to the foundational moment.

Today’s event in Zaria is coming a day after Prof Ibrahim Gambari recalled to his audience at the August 20th, 2025 ‘Evening of Tributes’ for the late Prof Okello Oculi how the old Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS) was made so popular by a parade of academic stars that its enemies changed the name to FARCE. As speaking is also doing especially if the speakers are high up in power terms, the FASS subsequently degenerated into a sham and shadow of itself as staff departed and the faculty even split.

Today’s event in Zaria is coming a day after Prof Ibrahim Gambari recalled to his audience at the August 20th, 2025 ‘Evening of Tributes’ for the late Prof Okello Oculi how the old Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASS) was made so popular by a parade of academic stars that its enemies changed the name to FARCE. As speaking is also doing especially if the speakers are high up in power terms, the FASS subsequently degenerated into a sham and shadow of itself as staff departed and the faculty even split.

Chaired by Prof Attahiru Jega who caused a stir at the event, Intervention understands it was a full house. Family members of past deans of the faculty represented those who are late now. Presences include representatives of the Emir of Zaria, Prof Ibrahim Gambari, Prof Attahiru Jega, Prof Ahmed Modibbo, Prof Uka Ezenwe, family members of Dr Mahmud Tukur, Prof Abdul Kaita (Chairman of the International Relations Students platform) Dr. Kole Shettima of MacArthur Foundation and many more others.

The event had its own mild drama. When Prof Attahiru Jega was introduced, the MC emphasised his having being Chairman of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) and former Vice-Chancellor. There was no mention of his ASUU leadership, a gap Jega protested, saying he considered that more definitive of him than the ones that the MC was more interested in. The protest sent everyone into a ruckus of laughter but from which the audience managed to quickly recovered and got back to business.

The substantive space was taken by ABU political scientist, Dr. David Moveh, who spoke on “African Academic Excellence: Implications for Politics and Development in Africa” at the maiden symposium to honor the past deans of the former Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, (FASS), ABU, Zaria at the CBN Centre of Excellence in Samaru, Zaria. The speaker tried to explain what contributed to its decline as well as the implications.

FASS, he said, was a creation of methodological innovations, interdisciplinarity and a culture of debate. Dr. Moveh who is a classic shon- of-the-soil and spoke from that lived experience of being born inside ABU, Zaria where his father worked as a FASS faculty staffer while he attended the university’s secondary school before cited went ahead to prove his thesis.

For methodological innovation, he cited the decolonial historiography that privileged oral sources as an example. With colonial sources, it meant the subaltern could speak in terms of what happened in the past as against Eurocentric stress on written sources. For inter-disciplinarity, he cited the arrangement whereby irrespective of any student’s major course, s/he could take electives from as divergent disciplines as s/he felt. For debates, he cited the Bala Usman/Bangura engagement on the causes of Nigeria’s economic nightmare. He was categorical that the splitting of the faculty into two had made that unobtainable.

For methodological innovation, he cited the decolonial historiography that privileged oral sources as an example. With colonial sources, it meant the subaltern could speak in terms of what happened in the past as against Eurocentric stress on written sources. For inter-disciplinarity, he cited the arrangement whereby irrespective of any student’s major course, s/he could take electives from as divergent disciplines as s/he felt. For debates, he cited the Bala Usman/Bangura engagement on the causes of Nigeria’s economic nightmare. He was categorical that the splitting of the faculty into two had made that unobtainable.

Other speakers basically agreed with his submission, with Prof Attahiru Jega, for example, saying that identity politics had taken a toll on the university system. People become principal officers of universities, especially Vice-Chancellors, more on where they come from or how they worship God and less on what they can offer, he said. but Jega also fingered the impact of national policies, particularly the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) and the different names it kept assuming as culprit. “At the end of the day, the universities were no longer where what happened in FASS of old could happen again”, he said.

Dr. Kole Shettima of MacArthur Foundation credited ABU, Zaria with a legacy of diversity, especially ethnic and religious diversity. There is no state that is not represented at student as well as staff level in ABU, Zaria, he said although Intervention could not ascertain if he was talking of today or yesterday.

Prof Ibrahim Gambari was commended for making possible over 20 ambassadors of mainly his former students in Zaria when he was in the UN system. On the whole, it was a big event as far as critically looking back at FASS as a centre of radical nationalist scholarship required for nation building in an emergent state. Of course, Nigeria is still an emergent state because it has not been able to settle many of the defining variables in state and nation building, an exercise that needs radical academic inputs, going by experiences from the West and, recently, East Asia.

There is no consensus on how Nigeria might not only be able to restore the universities to the heights they attained before the mid-1980s but also shield them from economic and political shocks. The resolution will depend on the balance of forces in the field of knowledge politics in Nigeria involving the Federal Government, private university owners, (I)NGOs, foreign investors, philanthropists and the students.