State repression of activists of the defunct National Association of Nigerian Students (NANS) in Nigeria in the 1980s is nothing comparable to 1994 genocide in Rwanda, for example but, like all cases of trauma time, it was a break in relationality on its own scale. A break in relationality is precisely what makes Jenny Edkins’s chapter, “Remembering Relationality: Trauma Time and Politics” in Duncan Bell edited text Memory, Trauma and World Politics, wave-making. Trauma breaks relationality or the interconnectedness that binds. Both those who survive and those who didn’t survive suffer Toni Morrison’s description of 9/11 as a “the thread thrown” between survivors and the dead. This complicatedness of trauma time is such that stories of trauma can have healing effects, especially if the narrator doesn’t get lost in blame game and bitterness in which everyone else but him or her is guilty.

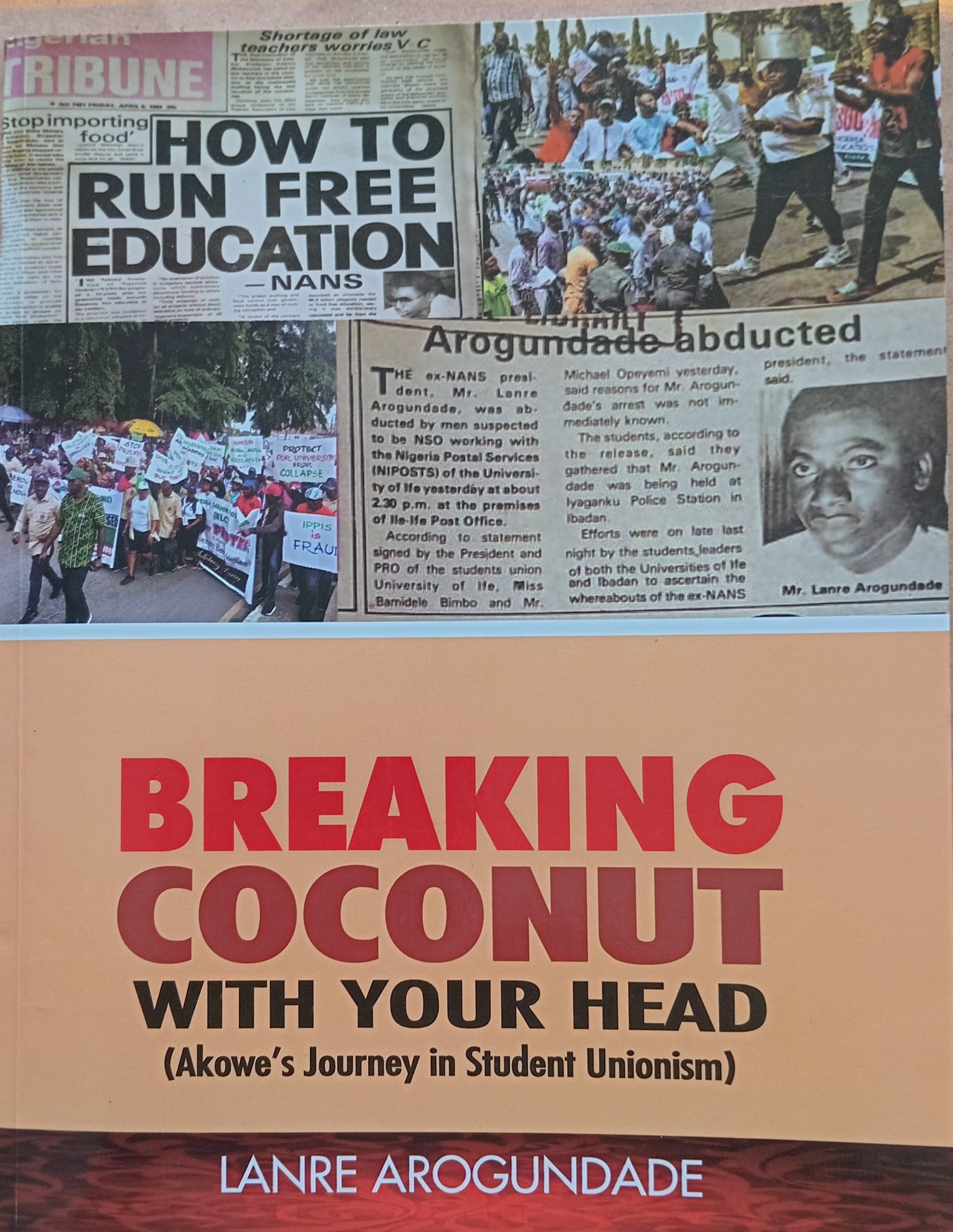

This is the background which makes Lanre Arogundade’s Breaking Coconut With Your Head inviting for all categories of potential readers. Breaking Coconut With Your Head is not an entirely new text, having been published in 2022. But the infinity of meaning any particular text can generate precludes any limitation on when its re-interpretation expires. Not with the coming establishment attempt at revivalism of youth politics in Nigeria which can benefit from the insights of a former president of NANS when NANS was NANS in Nigerian politics if that revivalism is not all politics.

The NANS Charter of Demands

In 241 pages, Arogundade serves his readers a thematized account of his time as president of NANS (1984/5). It was the era of commercialization including of education, providing the Arogundade regime with the jump-off point in radical contestation of the anti-authoritarian moment, based on the brand new NANS Charter of Demands thereto. This recollection is basically the story of that confrontation, starting from the obvious starting point of Arogundade’s ‘Morning Illuminates the Day’ account of his childhood in Chapter One. Arogundade was not born on top of green leaves but it was not far from that. Apart from two of his siblings, all else in his family were children of Abagbedi, the man who delivered mothers of their pregnancies in those days in Ijebu-Ijesha, today’s Ekiti State. As an Abagbedi child, Arogundade enjoyed no immediate immunisation, surviving rather on “local herbs, a variety of fruits and an array of fibres, carbohydrates and vegetables” (page 2). It is an interesting chapter if only because his story is applicable to most within his generation bracket: teachers who were very influential but thorough; the temptations and trials of rural lads but pupils whose primary and secondary school life was fuller and better organised than the chaos of today. It is also in this chapter that the reader finds how Arogundade got the name Akowe (writer or scribe). It was his choice of what he aspired to be, derived in itself from the sense of fulfilment in being the letter writer for parents who didn’t have the education to write letters to friends and relations through the Post Office that were functional in those days. Last point of significance is the earliest indicator of rebelliousness when this lad fought to be included in the end of year drama performance in his primary school, raining abuses on the Headmaster whenever he was not included. It was not surprising that, even before entering the university, he had participated in two protests, one local and the second, national. It was the Áli-Must-Go protest of 1978 (page 13)

By the time he entered the University of Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo University) to read Psychology, he had enough reservations against the status quo to be a bomb waiting to explode. Freshers could not contest elections but he found his way into the drumming and singing column of one of the presidential candidates, Femi Kuku. His provocation into students union activism at that point was the active presence of Wale Olaoye, Femi Falana and Greg-Obong Oshotse. Oshotse was to become the State House correspondent of The Guardian and Press Secretary to the late Mrs. Maryam Babangida. Again, it was not surprising he ended up as the Secretary-General of the Ife Students Union. Those who peep into page 28 will get a feel of the song composed in aid of that process and the wizardry of his one-man band, a student of theatre. Of course the chapter is not all about the excitement of students union politics in those days but deadly encounters with vicious policemen, the saddest being the protest on Ife Campus after the reported beheading of a student in Ife town.

All these provide the cultural, academic and social backgrounds to December 1983 when he was elected NANS President at UNIJOS. The communique spoke to a beleaguered civilian regime headed by Alhaji Shehu Shagari but before the ink on the communique dried up, Shagari had been swept away by the December 1983 coup, leaving NANS with a military regime one of its ringleaders was to declare very quickly would be intolerant of ‘undue radicalism’. The coup put NANS in a difficult situation. While it could not dismiss the popular enthusiasm for the return of the military, it could not also shirk responsibility of drawing attention to the illusion of military messianism. NANS found a way out in what Chris Abashi – Arogundade’s predecessor had said about December 1983: power was lying on the street and anybody could have picked it (page 72).

NANS statement underlying a conditional support for the junta included quick payment of workers’ salaries; putting a stop to retrenchment of workers; no attempt to increase cost of education; immediate nationalisation of foreign interests in Nigeria; developing local industries; total cancellation of IMF negotiation and loan and guarantee of human rights. (page 74).

It was a charter of troublesome demands as far as the Nigerian military was concerned. Although neither the Shagari led NPN nor the Buhari fraction of the ruling class were keen on an IMF Loan, a certain fraction in the military were willing to give in to that and were bidding their time. instructively, it was their chief ideologue who ruled out tolerance for ‘undue radicalism’. It was a discursive move which made policing of radicalism a key flank of the pro-IMF loan group. Policing radicalism put them in the position to decide when radicalism was due or undue.

An artistic portrait of the late Chris Abashi, Arogundade’s predecessor!

The first confrontation was not too far as the new students leadership headed from a NANS Senate meeting at the University of Benin straight for Dodan Barracks in Lagos. They wanted to see the Head of State or the Chief of Staff Supreme Headquarters. The length of the convoy amused as well as annoyed the military men at the gate. They couldn’t understand why a bunch of students would drive in such a long convoy to the seat of power and, without appointment, want to see the Head of State. These were military officers without ideological grooming b, say, a communist party or a national liberation movement. ‘As much as they tried to be polite, there was no doubting the fact that they thought something was wrong with our brain to just drive into a military fortress and demand to see the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces”, writes Arogundade on page 91. The troops directed them to the Secretary to the Federal Military Government. The convoy was divided. A section of them insisted they must see the Head of the State to deliver the communique of the NANS Senate meeting to him just as a section felt they had made the point and should go see the SFMG.

The rest of the memoirs is full of such encounters, especially with Vice-Chancellors and emissaries from General Idiagbon, the then Ooni of Ife and Arogundade’s mother whom the NSO as the secret police was called then, all aimed at annulling the May 1984 lecture boycott. Ahead of the boycott, NANS articulated the position in which a compulsory 20 % education tax on the profits of all foreign companies, the nationalization of commanding heights of the economy and total cancellation of the contract system as a means of building schools were three of the about 10 demands on the government (page 117).

“Defiance has a price tag” runs the header for Chapter Nine. The prices which came in the form of abduction, detention and being put on the watchlist of the security establishment in the case of Arogundade (others were shot dead by police, endured prolonged detention, expulsion, rustication and other forms of penalties) are what chapters nine, ten and eleven contain.

The great point in about the memoir is that Arogundade survived to tell the story of his own participation in what there has been nothing like in terms of NANS as a situated reading of where Nigeria was heading even as early as the 1980s, the ideological clarity in that reading, the organisational and tactical efforts to halt that degeneration and the repression unleashed on them for that stepping out. The radical nationalism reinvented by the students movement under NANS in the early 1980s is next in profundity only to the wording and worlding potentials of the Second National Development Plan scripted by the Super Permanent Secretaries of the Nigerian civil service of immediate post-independence. Beyond that, one looks into a very vacant national space for such originality and altruism, the vacant national space that has brought Nigeria to where it is today.

Currently, the executive director of the Lagos based International Press Centre (IPC), Arogundade is, in his own way, a statement in the resolution of the problem of transition from involvement at the level of students radicalism to a ‘mature’, settled activist. Femi Falana is a good example. Academics were a very good collective example. Journalists were too. Apart from the private or independent lawyers, those who went into journalism and academia have lost out. The relative autonomy they had no longer exists. The campuses, in particular, have become frightening, with academics dying of hunger and penury.

Arogundade deserves to be congratulated for documenting his experience. His memoir will be part of the raw materials from which a more comprehensive re-inscription of the defunct NANS may be possible. That should be a priority project in the light of the insecurity crisis and the general chaos that have followed the collapse of quality university or higher education in Nigeria.

Lastly, I got to know from reading the memoir why Arogundade could not give Intervention a copy of it free until Ambassador Nkoyo Toyo paid for the online platform. Arogundade is an Ijebu – Jesha man(?) Are they not all afflicted by the aradite culture former president, Olusegun Obasanjo personifies? I can write whatever I like. After all, I am not finding myself in Lagos or before Chief Obasanjo soon again!