By Adagbo ONOJA

For a minority ethnic group with the kind of empirical presence that Idoma elements have had in post-independence Nigeria, there is no risk in saying that the nationality has lacked discursive power awareness in their politics. Right from the First Republic to very recently, someone of Idoma identity was never far from the power hub: two ministers in the First Republic, the equivalent of two service chiefs under General Gowon; a military governor of one of the twelve states under Murtala, a super Permanent Secretary under the First Obasanjo regime, Chairman Senate Committee on Appropriation, a Minister and Chief Press Secretary to the president during Shagari regime; scores of military governors and strategic command positions running through the Buhari – Babangida – Abacha continuum and Senate presidency during the aborted Third Republic and the same position throughout the Yar’Ádua-GEJ -tenure are some of the positions that come readily to mind. On the basis of this list, Idoma can be called a dominant or hegemonic minority.

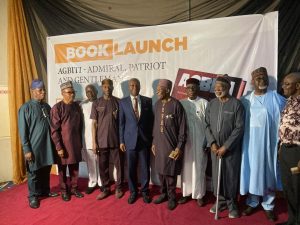

Representative faces at the presentation of Agbiti’s biography

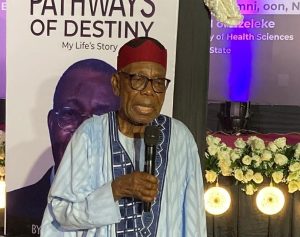

Dr Idoko explicating his destiny thesis at the presentation of his autobiography

Notwithstanding this solid presence, there is no collective Idoma self-understanding known to Nigerians. But that seems to be something they are transcending. In just the month of July, Nigerians are reading two biographical works on two different Idoma sons. It suggests a biographical turn in Idoma politics, particularly in the light of impending biographical works still being expected in the next few months. One of them promises to be truly explosive, to quoting the grapevine thereto.

The first of the two works now in circulation is the Fabian Enenche Owoicho edited biography of Admiral Francis Agbiti titled Agbiti – Admiral, Patriot and a Gentleman. The biography sells the defining narrative of Agbiti as a mid-ranking Officer touted as having the potentials to head the best Navy in the world but who was not allowed to head the Third world Nigerian Navy. Instead of such happening, Agbiti was hurled out of the Navy in June 2005 even after being absolved of complicity in releasing ‘M.T. African Pride’, an illegal bunkering vessel. And the booting out of Agbiti took place when his name was top of a list for appointment as Chief of Naval Staff (CNS) under the Obasanjo administration. It was an unlikely scenario, Agbiti having served as Secretary of the special Military Tribunal that tried, convicted and sentenced Chief Olusegun Obasanjo, Nigeria’s former Military Head of State to death for allegedly participating in a 1995 coup plot in Nigeria. He pursued the matter up to the Supreme Court which upheld his claims and restored his status and privileges. While the handlers of the text on Agbiti appear to be taking their time in terms of availability of the text and related details, the handlers of the second biographical work – actually an autobiography – are at work.

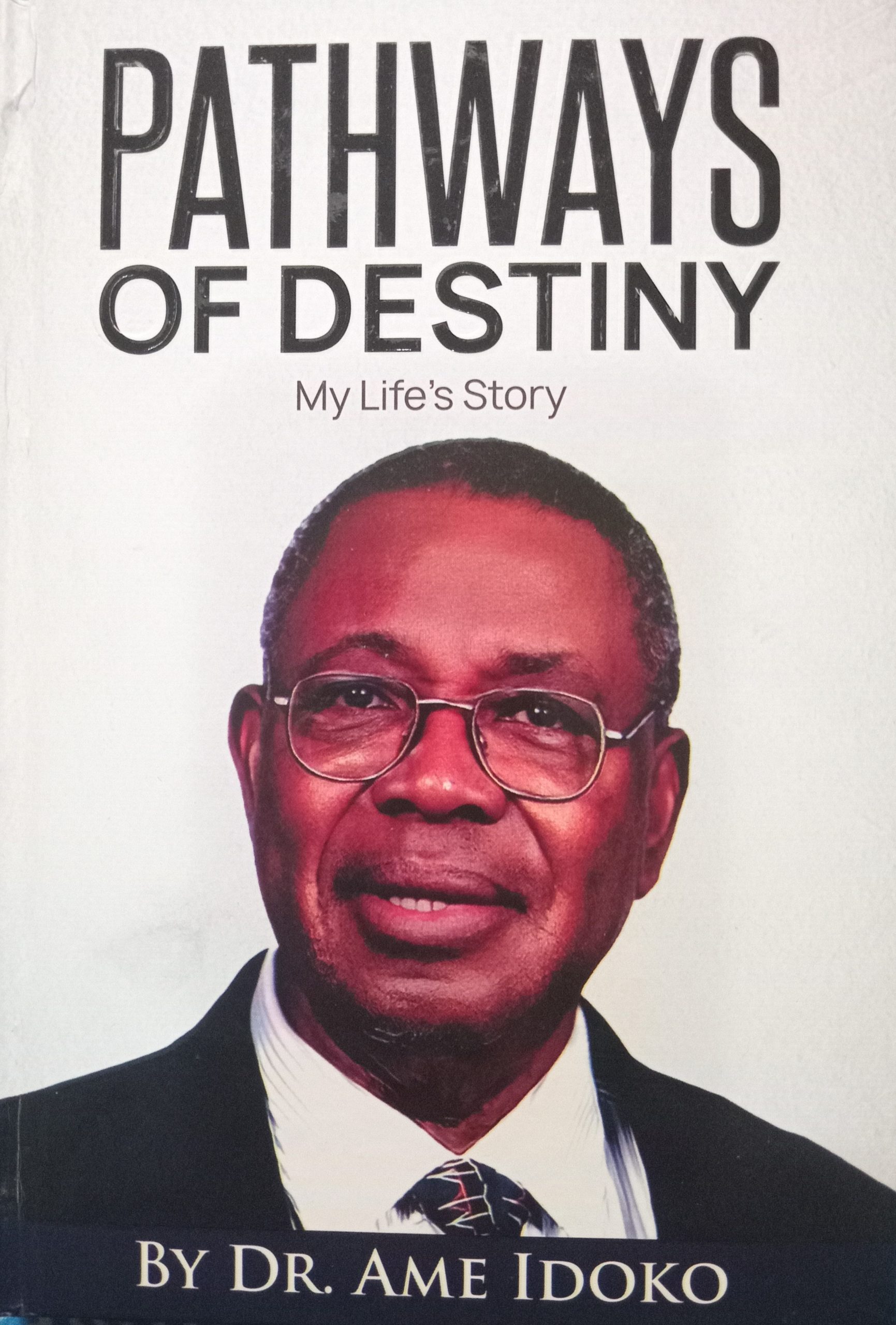

With Mount Saint Michaels Secondary School, Aliade Old Boys ideologues such as Comrade John Odah, they are circulating Pathways of Destiny: My Life Story by Dr. Ame Idoko far and near. The 157 page text is so uncomplicated it takes just a few hours to complete reading it. It may be uncomplicated but very rich in details and thematic coverage. Almost everything the unsuspecting reader would wish to know about life in the Nigerian rural space between the 1940s and the post war are there, be it the problem of date of birth in those days; traditional medicine, the central role of the Church in the educational development of Idomaland; the financial difficulties in going to school then; the long treks from one place to another, the primacy of Igbo teachers in the area in those days and the belief in the theology of destiny among the Idoko generation.

The details and themes are such that the autobiography is as entertaining and educative as it is infuriating. It is infuriating in the tragedy of the paradise lost with self-governing, such that made Dr Sam Mbakwe, Second Republic governor of old Imo State, weep repeatedly, unable to help himself from calling for the return of the colonialists. Mbakwe will weep triple more buckets if he were to come back today. The culprit is not far from imperialism at the end of the day but the Nigerian elite cannot be absolved of blame completely.

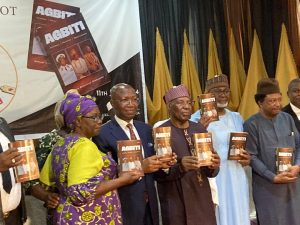

All for Agbiti: Chief John Eimonye, Chief Audu Ogbeh and Justice Ejembi Eko (rtd)

Faces at presentation of Agbiti biography

Dr. Idoko tells us how he fixed the day he was born because he didn’t know beyond that he was born in October of 1939. It is the story of most members of his generation born and bred in Okpoga type rural space in Idomaland at the time.

Okpoga is one of the 22 districts in the old Idoma Native Authority. Idoko came when there was no primary school in the area, compelling him to move from one of the six locations that had such school in the Idoma area to another, including staying with Igbo teachers who dominated the teaching job. One outcome of having to live under an Igbo teacher in Igumale, another of the 22 districts, was having to trek from there to Okpoga during a break. It took three days of trekking without shoes, denying Dr Goodluck Jonathan the privilege of being the only one who had no shoes as a school child. In all the three days, he either slept in the house of the local chief in the village the night caught him or in the house of the teacher in the area. There were no bandits, kidnappers or terrorists. All the hassles notwithstanding, Idoko concluded primary school in a boarding primary school, something which is not available to undergraduates anymore in wealthy Nigeria.

Yet another key theme is his entry into Mount Saint Michael’s Secondary School, Aliade, another pillar of his faith in destiny. His sister had to be married off for that to happen because no other alternative source of funding was available. Still, but for Mr Umeh, one of his Igbo teachers whom he impulsively decided to branch to his house at Okpiko while on a bicycle ride from Okpoga to Aliade to effect his withdrawal at the end of the third year, he would have been unable to graduate from Aliade (P. 21). His former teacher took pity on him and offered the two pounds he needed to resume. He writes about his happiness in keeping their relationship intact till Umeh died.

And so the story rolls on from Aliade to his HSC at St Gregory College in Lagos and admission to the then University College Ibadan which was a campus of the University of London. But before entering St Gregory as a HSC student, he had been to Lagos as one of the students selected from Aliade to reify Empire at Queen Elizabeth 11’s visit to Nigeria in 1956.

What is clear is how there is no escaping the Sardauna of Sokoto in all these. On Page 31 of the autobiography is a memorable reference to the late Premier. The reference is worth quoting for the intertextual message it embodies. “I was on a Federal Scholarship to St. Gregory, so there was no financial obstacle. Those of us from the North sat for the HSC entrance examination. The Northern Government, with the Sardauna of Sokoto as Premier in those days, decided that Federal schools like St. Gregory, Kings College, Anglican Secondary School and Igbobi College, were partially Federal Government grant aided but people from the North were not benefitting from it”.

Prof Innocent Uja, VC, Fed University of Health Sciences, Otukpo and book reviewer at it

Chief Stephen Lawani, the Ochagwu of Idomaland, a one-time student of Dr. Idoko and Chairman of the book presentation event in Makurdi July 13th, 2024

The first message is how federal scholarship solved an indigent student’s financial crisis in relation to educational access. The second is how the Sardauna, a Muslim, saw not Christianity but an opportunity for Northern students in well-established schools in the Lagos area. That is what is unlikely to be happening today as so-called Christian and Muslim leaders are fighting over uniform and such non-issues. Yet, it was St. Gregory that enabled Idoko to start making contributions to society in the form of an interim teacher at his Alma Mata – Aliade, teaching such names as Audu Ogbeh, Stephen Lawani and Chris Abutu Garuba while waiting to enter the University of Ibadan for his medical degree.

The themes are numerous but three more must be touched. Dr. Idoko writes about war in nearly the same sensitivity as Fanon. “War is horrific and there is no justification for wanting to plunge the nation into any sort of war”. He is inferring from his experience as a conscript and a Major during the Biafran War (P49). Idoko tells all that “the bloodshed, the deaths, the suffering of people, the uncertainty that plagues the people is an experience no one should wish to go through”, very similar to conclusions from the close encounter Fanon had with war in Algeria as to make him conclude that there is no healing or cure for victims of colonial violence than revolutionary violence. Unlike Fanon who resigned in protest to go into anti-colonial activism, Idoko had no such option as a conscript even as death missed him by a few minutes in one push by rebel soldiers into the hospital he was attached.

Away from the painful sides to a funnier story in the entire narrative. In 1971, Idoko arrived London on a British Council scholarship. Everything went fine for the two years he was there except the first night. Not aware of the heating system, he found himself freezing in the night, trying to cope by wearing all manner of coverlets. He managed to survive the night but only to discover in the morning from the attendants that all he needed to have done was to activate the heater. As Idoko writes now “I had no clue what he was talking about, and asked what a heater was. He then proceeded to show me that there was a heater to help regulate the room temperature” (P. 52). It is this sort of incident that makes Idoko’s story everyone’s story somehow because it captures the postcolonial character of the relationship between the colonial victims and the metropolis. It remains a hate-love relationship, a terrible ambivalence.

Lastly, Idoko arrived at founding an own medical establishment in 1979, naming it Madonna Hospital, reflecting the theological cant in upbringing as “Madonna is one of the titles of Mary, the mother of Jesus”.

So, in one man’s story, we see the progression of a society from colonial calamity to decay and disaster, making his story the Nigerian story. It is the more reason why everyone should tell his or her own story, especially those such as Idoko who are not haughty and are, thus capable of authenticity. His tight faith in destiny speaks to that. He didn’t set out to be anything beyond what Providence allowed but neither did he waste openings on the assumption that destiny will take care.

His biography is apt in a different sense: the mysterious ability of the Idoma man to fit easily anywhere in Nigeria, accepted, respected and trusted in both the North and the South, this being no chauvinism or essentialism. The inference from that is the danger of failing or incapability or unwillingness of beneficiaries of this advantage to write themselves in a manner that makes them and the Idoma nation winners in a highly pluralistic federation. The good news is that the Idoma elite appear to have accepted this paradigm as we shall see in a few months hence!