It seems safe to conclude that E P Thompson cannot be exhausted as a study in polemicising, that being what this piece suggests by moving him from heartland academe altogether to popular culture. It is culled from Unherd.

The Little Englander still shows that socialism can have a human face

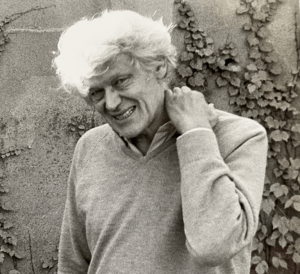

‘If Althusser was the logical end-point of Marxism, Thompson once wrote, then he would rather be a Christian than a Marxist’ (Avalon/Getty Images)

Edward Palmer Thompson was an unlikely Little Englander. He was born 100 years ago into the sort of polymathic, globe-trotting family that this country no longer seems to produce. His parents met in Jerusalem in 1918, where his mother taught French and Arabic. His father, “a courier between cultures who wore the authorised livery of neither”, spent much of his life in the Raj, where he befriended Nehru and sat at the feet of Tagore. Their eldest son Frank — polyglot, poet, and sometime lover of Iris Murdoch — died a hero’s death fighting the Axis in Bulgaria in 1944. There is still a village named after him 20 miles north of Sofia.

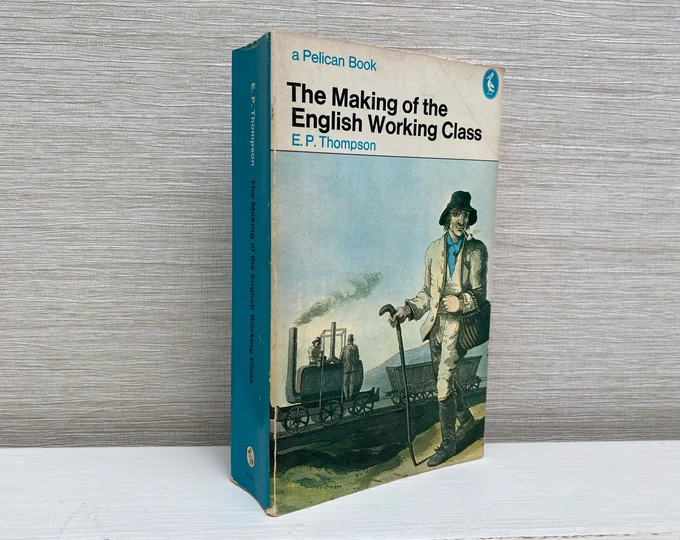

So if ever his fellow Left-wing intellectuals confronted him with the “Little Englander” charge, E.P. Thompson, whose monumental 1963 work The Making of the English Working Class made him the most influential British historian of his generation, had ample ammunition with which to respond. When the Scot Tom Nairn accused him of developing a “cultural nationalism”, for example, Thompson could protest that his political consciousness “cut its teeth on the causes of Spain and of Indian independence, chewed on a World War, and has been offered an international diet ever since”. But it is true that he was driven by a deep faith in the “common sense” of the English people, distinguishing him both from many of his Left-wing contemporaries and from the endless condescension of much of today’s political elite. And this is his greatest legacy: what he saw as the distinctly English tendency towards intellectual humility, scepticism, and empiricism.

Even so, in his lifetime Thompson sometimes liked to wear his reputation for parochial Englishness as a badge of honour. In his rather formless 1973 open letter to Leszek Kołakowski, he described himself as a “great bustard”, unable to soar in the sky with the majestic eagles of the Left. Other bright minds seemed to manage: “whirr! with a rush of wind they are off to Paris, to Rome, to California”. “I had thought of trying to join them”, he sighs, “I had been practising the words ‘essence’, ‘syntagm’, ‘conjecture’, ‘problematic’, ‘sign’.” But these efforts were futile: with his “stumpy, idiomatic wings”, his English wings, he would only “fall – plop! – into the middle of the Channel”. How English, to pat himself on the back beneath layers of ironic self-deprecation — even in his substandard essays, Thompson was a funny writer. Unlike the cigarette-smoking French philosophes, or their pot-smoking Californian counterparts, his English feet were planted firmly on the ground.

The iconoclast’s iconoclast

A deep suspicion towards rival, continental strains of Marxism runs through all Thompson’s writing (even his strange 1988 sci-fi novel). All sorts of people are in for a kicking in The Making — conservative followers of Sir Lewis Namier, liberals like R.M. Hartwell — but the principal target is announced early on. Too many Marxists, he decried, are gripped by the “ever-present temptation to suppose that class is a thing”. This was a terrible garbling of Marx’s actual meaning. Much “Marxist” theorising — Thompson liked to hang scare-quotes around the sects he deemed heretical — was built atop false premises. The purpose of The Making was to demonstrate that his definition of class as a relationship, apparently the authentic Marxist definition, was the only one worth dealing in.

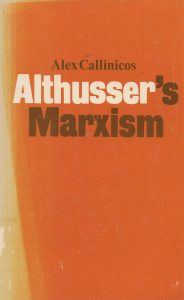

Thompson found other errors bedevilling Western Marxism, all emanating from “Theory”, or “the idiom of Paris”. In 1978 he wrote a spirited broadside against the thinker who most embodied this, and whom he seems to have hated most of all, the French philosopher Louis Althusser (this was two years before Althusser murdered his wife). The Poverty of Theory takes almost 200 pages to make an argument that can be summarised in four words: Althusser was a bullshitter. But these ideas were worse than senseless: they were popular. Althusser’s rabid dog “had bitten philosophy and sociology already”, infecting them with a slavish devotion to “structures” and smothering the individual agent in “Theory”. Althusser’s dog threatened to bite history too, or to chase it out of Marxist thinking altogether. In denying the “common ground for all Marxist practices”, historical materialism, Althusser was not really a Marxist at all by Thompson’s measure. The “rationality” of Althusserian Theory was a hoax. “We have been drawn into an illusionist’s parlour.”

It was not just that Thompson found Althusser’s writing obscure and evasive, and that he was at a loss as to why his ideas had amassed legions of disciples; it was also that Althusser’s “inverted world of absurdity” had nothing to say about practical politics. Althusser, the “rigorous Parisian philosopher”, had retired to his “secluded observatory”. Whether the point of philosophy was to interpret the world or to change it, Althusser was capable of neither. All this was a handy foil for Thompson’s image of himself both as a down-to-earth English thinker, and a determined political activist. But this conceit of English soundness versus high-minded French pretension naturally made room for certain exceptions: Thompson often feared that Parisian tentacles had penetrated the British Left. Tom Nairn was one manifestation of this, but across his work Thompson reserved his most withering sneers for Nairn’s comrade-in-crime, Perry Anderson.

Thompson bore a grudge against the Old Etonian Anderson because, in one of the internecine squabblings for which the Anglo-Left is justly famous, Anderson had booted him and his friends out of the New Left Review. Recounting these events with some bitterness and the usual irony, Thompson cast Anderson as the “veritable Dr Beeching of the socialist intelligentsia”. When Anderson took over the NLR, “all the uneconomic branch-lines of the New Left were abruptly closed down” — and after rigorous intellectual costing, Thompson’s own contributions fell foul of swingeing cuts. Thompson’s New Left had been unceremoniously supplanted by the “New New Left”: younger, cooler, and au fait with whatever was in vogue on the Left Bank.

In Anderson’s and Nairn’s adherence to the continental dogmas, Thompson detected a deep anxiety that their native land was somehow defective. For Nairn, the doyen of Scottish nationalism, things might perhaps be set onto their proper course if Britain were broken up altogether. Anderson broadly shared the view that England was a historical humiliation, a fossil of feudalism that the tide of history ought to have swept away. The 19th and 20th centuries had passed by embarrassingly revolution-less; Marxism had arrived much too late, when industrial capitalism was already entrenched. When Nairn and Anderson looked to other countries, at least according to Thompson’s parody of their position, they felt only a crushing, self-loathing inadequacy. In those other countries things seemed “in Every Respect Better”:

Althusser so battered by E.P Thompson that it won’t be out of place to renew the question, why?

“Their bourgeois Revolutions have been Mature. Their Class Struggles have been Sanguinary and Unequivocal. Their Intelligentsia has been Autonomous and Integrated Vertically. Their Morphology has been Typologically Concrete. Their Proletariat has been Hegemonic.”

The jargon wasn’t much of an exaggeration of the Nairn-Anderson thesis. “One can almost hear the stretching of historical textures,” Thompson said of Anderson’s approach to history, “as the garment of English events is strained to cover the buxom model of La Revolution Française”. Like Althusser’s structural “Marxism”, this was practically impotent as well as intellectually hollow. England, after all, “is unlikely to capitulate before a Marxism which cannot at least engage in a dialogue in the English idiom”.

What was this “English idiom”? For Thompson, it was partly a reflection of his own aesthetic tastes. His worldview, he often stressed, owed as much to William Blake and William Morris as to Marx. He was as much a Romantic as a Radical: and the tragedy of English history, The Making concludes, is that these two strains of thought came to run a “parallel but altogether separate course”. For socialism to succeed in England, the two would have to be welded together; and for this to be achieved, the teachings of Marx would have to adjust themselves to the English spirit.

Thompson’s mission in The Making was to provide a glimpse of what this would look like. The book itself is an exercise in uniting hard-nosed scientific critiques of industrial capitalism, in the manner of Marx, with a moral critique more in the vein of Blake or Morris. In his section on the children’s workhouses, for example, he concludes pages of weighty analysis with the affecting line that “the exploitation of little children, on this scale and with this intensity, was one of the most shameful events in our history”.

The Making also sketches out a type of Romantic Radicalism in the English idiom which, though now lost, once prevailed. What allowed the 19th-century polemicist William Cobbett to prevent the Radicals and Chartists from becoming the camp-followers of the bourgeois liberals of their day was precisely his fluency in this English idiom. He extolled Magna Carta, the Bill of Rights, and the Common Law. “We want great alteration,” he declared, “but nothing new”. For Thompson, the Radical cause had proved itself strongest in England when it worked with, not against, the constitutional grain: when it harked back to the “prodigious mind of the immortal Alfred”, or looked forward to “the restoration of old English times”. Thompson was charmed by this type of historically-oriented English socialism because it placed the freedom of the individual at its heart.

And in this respect it was diametrically opposed to the oppressive Marxism (or “Marxism”) found across the Channel. Stalinists and Althusserians — Thompson made clear that he saw no substantial difference between the two — look upon their fellow men as Pavlov’s dogs: “if an economic crisis comes, the people will salivate good ‘Marxist-Leninist’ belief”. But this was a lesson disproved, in the first instance, by English history. “Roundhead, Leveller, and Cavalier, Chartist, and Anti-Corn Law Leaguer, were not dogs; they did not salivate their creeds in response to economic stimuli; they loved and hated, argued, thought, and made moral choices.” That they made such choices was what made them human.

Thompson knew that he was fighting a losing battle. In the decades since his death, the Left has sequestered itself ever more within the sociology faculties while “Theory” has proliferated in inverse correlation to its electoral fortunes. But, more than an academic culture warrior avant la lettre, Thompson’s socialist humanism also has something to offer beyond the Left. He should, I think, be embraced by liberals of all stripes — whether or not he would have approved of such an outcome — as a profound voice against excessive bureaucracy, against the “machine”, against anything that seeks to limit the scope of human possibility and reduce us to barking Pavlov’s dogs.

If Althusser was the logical end-point of Marxism, Thompson once wrote, then he would rather be a Christian than a Marxist: at least Christians value the conscience, dignity, and free-will of the individual. The word “agency” may now have surpassed “syntagm”, “conjecture”, and perhaps even “problematic” as a bromide of historical and philosophical writing. But the cliché should not be taken for granted — and we have E.P. Thompson and his “English idiom” to thank for it.

the author is a History student at Trinity College, Cambridge.