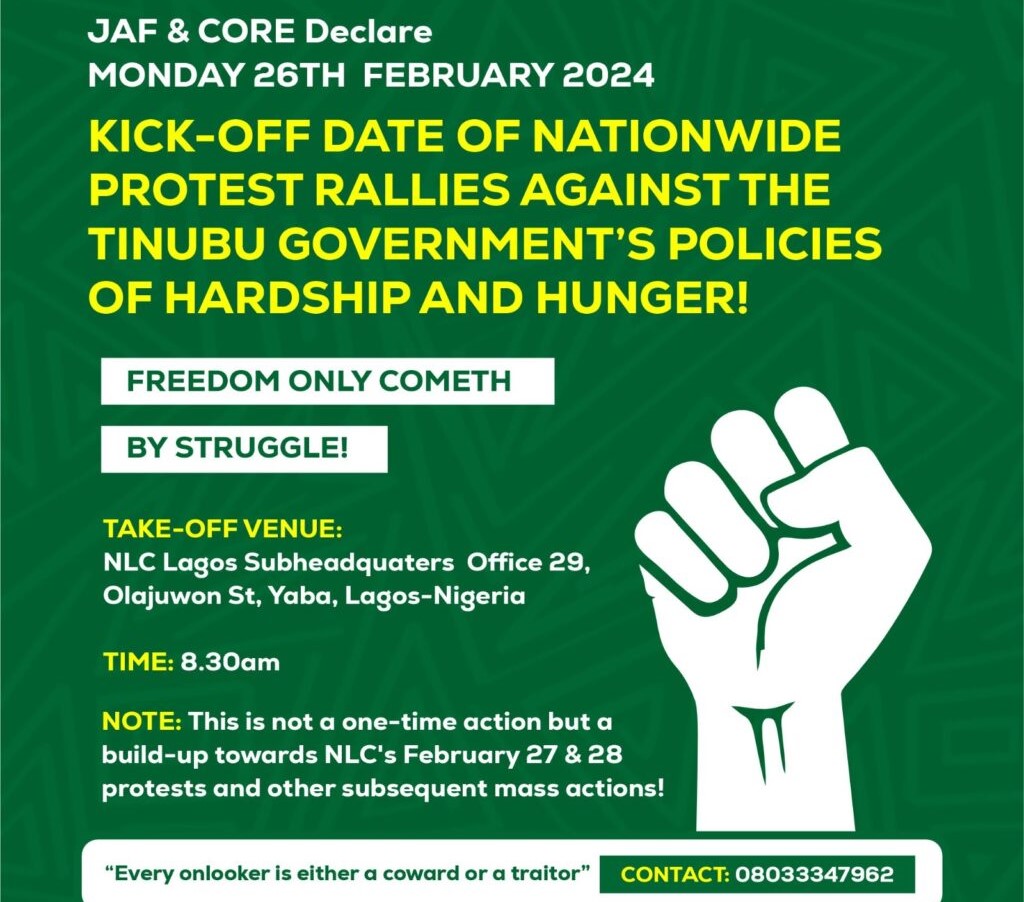

Barring last minute cancellation or postponement or similar surprises, the Nigerian Labour Congress (NLC) is rolling out its affiliates at last for a test of strength against the Tinubu administration February 27th and 28th, 2024. The NLC-led protest would be unique because that would be the civil society side of the spate of protestation of hardships brought into being by the Tinubu regime. But it would be the ultimate paradox of the Tinubu Presidency. And why not?

In February 2012, President Tinubu was complicit in a mass protest that considerably delegitimised the Dr. Goodluck Jonathan administration well before the 2015 presidential election. (more on that statement shortly as the statement is not the paradox in itself now). Rather, the paradox in the impending NLC protest is a Tinubu who is versed in instrumentalising protests against a predecessor but who could not inoculate his regime against being protested on a far worse ‘crime’ of imposing unbearable hardship on people. So hard that no regime friends are out there rolling up the sleeves for the president. There is surely something paradoxical when a regime headed by a politician who has been very close to activists and activism could be implementing a reform package that would generate civil society anger as has been the case. There is a paradox in a Tinubu regime parading ministers, many of whom have never read even a page of what the leading economists – Adam Smith and John Maynard Keynes – have to say on the dos and don’ts of reform, especially reform in an agrarian economy. Is it ignorance or sadism? Or is it possible that President Tinubu is yet to unfold a Tinubu cabinet? Might it be an illusion to expect anything better? As things are, the level of hardship is such that the civil society which has, hitherto, been missing in terms of organic action is out at last, barring any shift of position.

The global slogan animating civil society activism is not new in Nigeria but might be coming back with greater force

In recent Nigerian history, there are three clear examples of when the civil society that Intervention has in mind came to itself. These are the 1987 and 1989 anti-SAP riots led by the NANS; the June 12 protests led by the Campaign for Democracy (CD) initially and the Democratic Alternative (DA) later. Both the CD and DA were coalitions of gender, students, human rights and middle class professional associations (academics, doctors, lawyers amongst others. The last would be the February 2012 nationwide anti-subsidy protests by the nameless, loose coalition that superintended it.

The above background is the sense in which the civil society may be said to have been missing in action at a time of hardship protests across Nigeria. It was missing to the extent that protests have broken out without bearing the collective stamp of the numerous urban based NGOs organising, agitating and occasionally testing strength through a diverse set of actions such as press statements, special reports, going to court or embarking on street actions. Instead of such a collectivity, the protests so far are the handworks of youth, (market) women, unemployed and the broadly excluded or disempowered poor.

While it is true that these categories must be conceptualised as part and parcel of the civil society to the extent that they are not part of the political society (the branches and institutions of the state), they can only constitute a civil society peculiar to Nigerian social setting: a continuation of the voluntary agencies building schools, the town/village meetings acting as channels of redistribution, taking care of the burial of members and sending financial assistance to members in need and their rural versions.

The foregone reminds us of the problem of talking about the civil society in a non-industrial setting such as Nigeria. Can we talk about the civil society as actors in the space between the modern state and the peasantry or the non-capitalist part of the society in an economy in which everyone – including those smart lawyers, journalists, bankers, accountants – are, theoretically, peasants?

Problem number two with the concept of civil society generally is the sustainability of the distinction between the civil and political society beyond Gramsci’s inability to completely transcend the limits of structuralist reasoning. Although Gramsci was the first to be so perceptive regarding the potency of the civil society in the inter-class struggle for power, he was still locked in the binarism of the working class versus bourgeoisie; state versus civil society; organic versus traditional intellectuals and son on. There are thousands of civil society organisations that are closer to classical capitalism and state power than the non-state sector.

Well, now, an NLC-led civil society action is here. No one can say the civil society is missing again but how far can the NLC go? What problems is it likely to encounter?

The civil society has been the theatre of politics in the post-Cold War. The most powerful insight about the civil society in the post-Cold War is that which generally connects them to constructivism. Specifically, they are called managers of meaning. In other words, they derive their power from exceptional capacity to put things in perspective and thus determine the terms by which social phenomena are understood by the rest of the society. The assumption is that to determines the terms by which complex social phenomenon are understood is to be the most powerful because such an actor provides the framework for collective action at crucial moments as well as in everyday praxis.

Outside of the constructivist root of civil society power is Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s theory of globalisation in their book called Empire and which seems to be what the World Social Forum (WSF) enacted – no hierarchy, no long list of leaders or elaborate structures. The book – a post-Marxist theoretical outing – has been a paradox too: it has not remained as popular as when it came out initially but it was the WSF enactment of it that so rattled the global order as for The Economist to ask in 2000: Who elected Oxfam? The Economist used Oxfam to interrogate the actorness of global civil society organisations that have grown so powerful from the clarity of their perspectives and their tactical moves too. Although just a phrase in a long article, The Economist’s ‘who elected Oxfam?’ has led to a big debate that is still going on in normative political theory, even after several journal essays and books, particularly the one by Laura Montanaro, the University of Essex academic by that title.

The debate The Economist has generated with the question is who do these civil society rattling the global order by making meetings of multilateral institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank impossible represent? The Economist inferred that they represent nobody because nobody elected them. The question is whether representation is validated only by being elected.

At a meeting of the G-8, journalists shot Bono, the Irish singer, with the question whether the poor Africans he claimed to represent gave him such a verdict. He shut them down by answering that those Africans so poor as to know if it is Christmas didn’t give him any verdict but wouldn’t mind he was a debt relief campaigner insisting the G-8 cancelled Africa’s debt.

There are different other lenses for looking at the civil society. The question is whether the civil society in Nigeria can replicate some of these scenarios, particularly now. What could help it replicate some of these scenarios and what are likely to hinder it from replicating or even creatively advancing beyond them? In asking these questions, Intervention is dismissing any international or global versus national binary.

Might reforming an agrarian economy so recklessly be out of ignorance or sadism or the eve of a radical President Tinubu?

One positive factor is the context of the protest. Price of stuff in the markets are so high that the NLC may need not persuade many before they join in the protest.

Two and still a helpful background is the slim social base of the Tinubu regime. It is not only slim at the class level, it is also slim at all the fault lines, with the possible exception of the generational. It is a very selective regime unlike Obasanjo or Jonathan government.

Still a helpful factor is NLC’s experience of protests, notwithstanding the differences between the current set of labour leaders and those that define the NLC in popular imagination. While acknowledging that gap is important, acknowledging that traditions die hard would resolve doubts in favour of a powerful outing.

The fourth helpful indicator is larger forces in the society in solidarity with popular action that can compel the government to back down from hiding ignorance and incompetence under the notion of reform. It would be the moment in Nigerian history when the civil society can organise to discipline governance, not only in the case of Tinubu but forever.

But no one should doubt the capacity of the Tinubu regime to organise its own civil society. It is reckoning with such possibility that Intervention calls the regime a constructivist regime or the Tinubu imaginnaire. After all, it fabricated its own bishops. Constructivism is all there is to politics and that is not what is surprising about the government. What would be surprising is regime civil society is able to assert itself at all in the current balance of forces.

Is it then possible that the civil society in Nigeria may finds it difficult to assert itself because majority of the activists probably lack a good grasp of the ontology of civil society power? There is no doubt that the higher echelon of the civil society is absolutely well educated but is that the case with the young graduate who entered into civil society fireworks yesterday? In the campaign against manufacturing and sale of landmines and which won the coalition leader Nobel Peace Prize in 1997, the press statements were so philosophically brilliant that a major news outlet such as CNN didn’t edit them before using them even though CNN has an ownership structure that could be a beneficiary of sale of landmines. Can the civil society in Nigeria muster such capacity in a particular campaign? Does there exist an institute where civil society activists are groomed in the basics of that line, irrespective of the particular CSO employer?

With the pro-Tinubu faction of the Afenifere asking Yorubas not to participate in the upcoming protest, can it be taken for granted that ethno-religious and cultural fault lines will not be mobilised to try to undermine the protests or turn it into something else? The series of warnings to the government in the past one month from leaders of religious, traditional and ethnic platforms, prominent individuals, governors, newspaper editorials and so on would suggest that, for once, there is consensus that the people in power haven’t got it right. But that could also be over-assuming too.

Anti-SAP protests were superintended by the Socialist Congress of Nigeria (SCON). It was substantially the force at work also in June 12 struggle. Right now, which is the radical organisation behind the civil society today, with particular reference to the required ideological guidance should the push come to a shove?

All said and done, this is the age of the civil society in a world in which coalition building (in the Gramscian sense of the ‘collective will’ wider than the working class) is the ONLY way to go. The impending protest would, therefore, be more important in projecting this onto the agenda of politics in Nigeria than what it achieves immediately. The grand strategy is moving this society to where the people can discipline any government in Nigeria, be it Tinubu or whoever. It is the absence of that culture that is the trouble with Nigeria. In other words, it is not free and fair election that guarantees democracy. Rather, it is the balance of forces between ‘people’s power’ and the ‘people in power’ that is decisive. What is known in Political Science as the state will remain the greatest evil in human history but a very necessary evil. Disciplining of people in control of the state is thus the central agenda of politics in the 21st and subsequent centuries. Since the civil society is the theatre of the politics of disciplining state power, civil society politics (training and orientation of its cadres, funding, tactics, etc) is also the core of emancipatory politics.

Nigerians will not be witnessing the first civil society protests in her history but the civil society protestation of hardship unleashed by the Tinubu administration should be seen as a different and most symbolic action in Nigerian politics against the background of the above paragraph

On Tinubu’s Statement Against Jonathan’s Subsidy Regime in 2012

Now, On Tinubu’s February 2012 statement against Dr Goodluck Jonathan’s subsidy regime. Apart from behind the scene moves in support of that protest, Asiwaju Tinubu circulated a statement that, fortunately for him (President Tinubu), nobody is deconstructing. The statement is being massively circulated by regime opponents but circulating it massively without deconstructing it is a waste of time. Nobody is automatically liable for statements made in the past without further deconstruction. If meaning is what is unsaid, then no such liability lies in the February 2012 statement against subsidy by President Tinubu. This is an aspect of politics that does not seem well appreciated in Nigeria as readers or viewers tend to take things on the surface. The meaning of a text (an opinion article, an essay, a book, a text message, a cartoon, a video, a podcast, etc) does not lie with the author(s) but with reader(s) because no language or sign system has a fixed, final meaning. The word ‘Go’ in a text could actually mean ‘Come’, depending on a reader, listener or a viewer. So long as we read texts on the face value, so long we would be vulnerable to being deceived by pastors, politicians, lawyers, teachers and the likes!