Vice-Chancellors in Nigeria, for example, may not need to fight for pay rise because, as critics of the system would say, they can get whatever they want informally. In Australia, however, not much is opaque and the information available shows that many if not all earn higher than the prime minister. Well, Australia is not Nigeria, that still speaks to the logic that academics are some of the best paid workers across the world except Nigeria, perhaps. This is an interesting piece from University World News which itself got it from Honi Soit. Each of the two titled it differently and so is Intervention although for the latter, it is about how fourteen Vice-Chancellors received more than one million dollars in pay amid a crisis in university governance structure, allowing for conflict of interest to thrive.

By Khanh Tran

Following analysis of Australian Vice-Chancellors’ (VC) pay, the University of Melbourne’s Duncan Maskell tops the list with a mammoth $1.5 million salary, followed by Monash, Flinders and Queensland universities.

Members of Australia’s Group of Eight, (Go8) universities

Vice-Chancellors presiding over prestigious Group of Eight (Go8) universities take home some of the most generous pay packages in the country, with the University of Sydney’s Professor Mark Scott and UNSW’s Professor Attila Brungs receiving $1.15 and $1.05 million respectively. Adelaide University’s controversial Professor Peter Hoj also rakes in $1.015 million, joining thirteen other VCs who receive salaries exceeding one million dollars.

Meanwhile, the ANU’s Professor Brian Schmidt receives a comparatively lower salary standing at $660,943 a year within the group, inclusive of superannuation and excluding housing costs which Schmidt is responsible for paying. Others who share Schmidt’s pay range include Charles Darwin’s Professor Scott Bowman and Wollongong’s Professor Patricia Davidson.

The lowest paid VC is the specialist University of Divinity’s Professor Peter Sherlock, who took home $260,000. The institution, unlike other universities, is an amalgamation of various Christian denominations’ seminaries.

Excluding America’s exceptionally wealthy universities, Australia’s VCs command some of the most favourable salaries anywhere in the world, drastically dwarfing their European and British counterparts. One of the UK’s highest-paid VCs, UCL Provost Michael Spence—who used to lead Sydney University—commands $960,000 annually before factoring in rent that exceeded $90,000 in 2021. According to information obtained by Honi through a Freedom of Information request, Spence now resides in London’s posh Bloomsbury Mansion.

The figures also reveal that Australia’s VCs are paid far higher than those occupying the nation’s highest offices, with the majority of VCs’ pay packages dwarfing that of the Prime Minister, who receives just shy of $550,000 a year.

Questions raised over the effectiveness of UCC’s Code

In 2021, the University Chancellors Council’s (UCC) Australian Universities Vice-Chancellor and Senior Staff Remuneration Code was introduced, encouraging disclosures of VC and university executives’ remuneration. This came on the heels of what has been described as “lavish” pay packages for Australian VCs that saw former Federal Education Minister Alan Tudge call for pay to align with “society’s contemporary expectations and norms”.

“Reporting of governance and remuneration should be included in the Institution’s Annual Reports,” the code said.

However, the UCC Code is being perceived as an ineffective measure, with standards of disclosure varying drastically from one university to the next. While universities such as USyd and UniSA disclose a broad pay range, others such as Western Sydney University fully disclose the pay of individual executives short of identifying non-monetary benefits.

One of the key measures the UCC’s voluntary code uses to benchmark the appropriateness of VCs’ remuneration is the gap between an institution’s median salary compared to its senior executives’.

“UCC will consider other statements of intent or principle such as the relativity between the median salary for a University and that of its VC and Senior Staff,” the code’s guideline reads.

However, the guideline places the onus of proposing a “statement of intent or principle” on universities, meaning that university management are, as the voluntary nature of the code implies, not compelled to consider median salary to construct a meaningful boundary from which remuneration may be considered inappropriate by the UCC.

According to a USyd spokesperson, Scott’s pay, exceeding one million at USyd, “sits within the guidelines outlined in the [Universities Chancellors Council’s] voluntary code”.

Yet analysis by the NTEU’s Ian Dobson in 2018 found that USyd’s median salary stood at Higher Education Worker Level 7 (HEW 7) of $90,160–$98,224. Today, calculations of data from the University’s 2021 Annual Report indicate that its median salary remains the same four years on. This means that Scott’s salary currently exceeds the average USyd professional staff by a staggering tenfold.

According to public organisation governance expert Dr Rebecca Boden, universities today see themselves primarily as income generators rather than knowledge-building institutions.

“We found a correlation, albeit I stress correlation, not causation, between these massive pay increases as universities marketised and they move from being a collegial institution to seeing themselves as businesses,” Boden told Honi, referring to research conducted by her and the late Deakin University Professor Julie Rowlands.

This tectonic shift over the decades from Margaret Thatcher and Bob Hawke’s governments in the UK and Australia, for Boden, came to enable universities to justify exorbitant expenses by citing universities’ monetary contribution to society and institutions’ large size.

Indeed, the UCC voluntary code’s pay guidelines stipulates that senior executives’ remuneration must be “fair to the individual and the institution”, taking into account “responsibility, accountability, scale and complexity” of the sector’s “30 billion” dollar economic value.

Lack of controls on remuneration governance and transparency a major issue

Compared to other countries, the pay of Australia’s VCs remains largely shrouded in opacity. This is in contrast to the United Kingdom where, since 1994, universities have been compelled to disclose this information in their annual reports. Aside from the base salary, institutions are required to disclose the relevant VC’s pensions and benefits. No equivalent set of laws exist in Australia to govern the disclosure of salaries nor governance structure.

Prof Loise Richardson, immediate past VC of Oxford University in the UK

Unlike other countries, Australia has relatively lax oversight of VC and executives’ salaries, with no legislated mechanism to compel universities to declare senior management’s payment aside from the press’ routine reporting on the issue every year.

Compounded in this is the conflict of interest that comes from VCs’ membership of university subcommittees, which presides over their own salary.

Vice-Chancellors who do not sit in the same committee that determines their remuneration are rare, with Victoria University’s Adam Shoemaker and USQ’s Geraldine MacKenzie not being a member of their institutions’ remunerations committees. In 2017, Bath University’s Glynis Breakwell resigned when England’s university funding council, HEFCE, condemned Breakwell following a sustained campaign by the local University and College Union (UCU) campaign together with student activists.

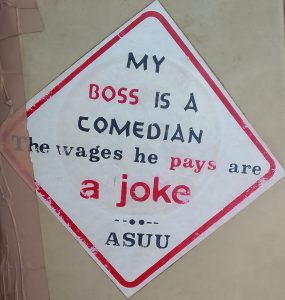

In Nigeria, for example, the story is different although, VCs are not mainstream academics in Nigeria

For instance, the University of South Australia’s David Lloyd attended all three meetings of UniSA’s Senior Remuneration Committee, and the same applies for other VCs across the country, including former UNSW VC Professor Ian Jacobs and USyd’s Mark Scott.

In USyd’s case, a university spokesperson confirmed that Scott’s pay is set by the Senate and that the VC has declared a conflict of interest and is not present when his pay is discussed.

However, Boden argues that both arrangements raise serious questions: “Even if they [VCs] are outside the room for when individual discussion of their salary is going on, they set broader strategy and rules surrounding pay,“ Boden said, referring to Scott’s declaration of interest. “Then, their salary almost drops out and automatically gets fixed by the salary strategy.”

She pointed out that, even if a VC or an executive were conflicted off individual discussions about their pay, the fact that some executives are appointed by the VC means that there is a herd mentality to inflate bonuses and rewards rather than exercise restraint. This comes from her view of the five-year period following Breakwell’s resignation when the UCC’s counterpart in the UK, the Committee of University Chairs (CUC) released its own voluntary code following the Breakwell scandal.

“The transparency requirements in many ways are a legitimising device for marketisation. My hunch is that it [the CUC voluntary code] hasn’t had any restraining effect [on salaries],” Boden said. “I don’t think these voluntary codes will do anything.”

From her perspective, Australia faces an acute crisis in university governance structure with rampant conflict of interest and a lack of decision-making independent of VCs and their senior executives.

Sustained student campaigning and Academic Salaries Tribunal needed for genuine, lasting reform

Ultimately, for Boden, the astronomical rise of VCs’ salaries in the past decade represents a critical “market failure”, in the sense that no internal reforms by university executives can attain meaningful transparency and address the widening pay gap. Instead of relying on internal “tinkering” within universities, she says that the government must intervene to curtail VC salaries and restore public trust in higher education.

Furthermore, she recommends that Australia needs a federally operated “Vice-Chancellors’ Remuneration Tribunal” to oversee VC pay packages, citing Australia’s former Academic Salaries Tribunal, who used to investigate and determine academic salaries, as a model example.

“I think it [reform] has to come from the government because it has got skin in the game because they fund universities. So this has to be a regulatory matter because the universities are incapable of regulating themselves, a market failure.”

Ultimately, Boden is certain that it will take sustained pressure and awareness from student, staff and unions such as the UCU or NTEU to push the government to hold VCs accountable and reduce the increasingly significant pay gap.

“It (Glynis Breakwell’s resignation) was drummed up because of student and staff activism,” said Boden.

“It needs to be a national campaign where all students and staff have to come together and say: ‘This has to stop’. That would be much more effective because one VC resigning doesn’t solve the problem because you’ve not changed the system.”