By Adagbo Onoja

This is an abridged version of a 2007 column. It has been edited to reflect current concerns.

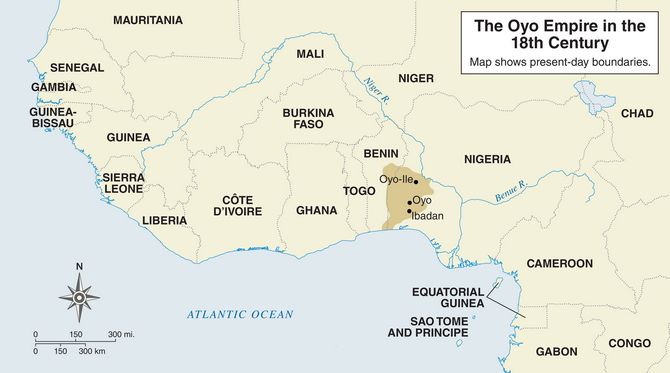

Although Nigeria has not experienced a transition anarchy in the magnitude of what happened in Somalia, Liberia, Rwanda, Burundi and Sierra Leone, etc, it is nevertheless going through a harrowing moment. That makes appropriate this narrative of the ruin of old Oyo’s democratic order when its leaders plunged into the Atlantic slave trade, with the violence of the slave raids turning inward and then the eventual implosion into a fierce civil war in the early part of the nineteenth century, to quote Ekeh.

This fate of the old Oyo Empire is captured in a story by the late US based Nigerian theorist, Professor Peter Ekeh, who illustrated “A Case for Dialogue on Nigerian Federalism” with it in a Keynote Address to the Wilberforce Conference on Dilemmas of Democracy in Nigeria in 1995. And the story goes: Soldiers from an Oyo satellite town, ruled by a Bale, a feudal lord, were pressed by their leader into the civil war. They lost. Rather than being taken as prisoners of war, as it would be the case in previous normal times, they were now sold into the slave trade. Six of these soldiers – all grades of them: general, horsemen, foot soldiers, and of different ages – found themselves as slaves in a Caribbean sugar plantation. One afternoon, as they labored in the field, three new slaves were brought in to join them. One of the ex-soldiers looked up to observe these new labor recruits. He then cried out: “Oh no, oh no, oh my God: It is the Bale himself.” The others joined him in this emotional recognition of their ruler back home in Yoruba land and Oyo nobility and commoner, all now slaves, wept together at the fate of their fallen ruler and their fallen civilization. None of them knew of the fate that had befallen their wives and children and relatives at home. But each of them had paid a heavy price for the mismanagement of Oyo’s public affairs”.

Ekeh’s conclusion from the story is that Oyo’s misfortunes in the nineteenth century should provide us with a parable from which to examine Nigeria’s current predicament. That is in the sense that Oyo was not conquered from outside but collapsed under the weight of its own mismanagement even though it could have resolved its problems internally through dialogue and its own tested institutions in the way that some of us grew up to learn that politicians were doing. That is howling at each other on the pages of newspapers in the day time but meeting at night to take crucial decisions when it came to state matters. This is not the situation today even with a completely decentered state.