Written for Daily Maverick, the author gives us a more radical view of Jesus, the real substance of the Easter festivities.

By Drew Forrest

“What Jesus did was plant the seed of the left-wing outlook – the idea that society has a special duty of protection towards its most vulnerable, the poor, the sick, the young and the old. Together with his world-negating refusal to compromise with authority, this has been Jesus’s lasting political bequest. His insistence that “the last shall be first” has had volcanic reverberations down the ages”

Yeshua ha Nozri – Jesus of Nazareth – lived through a politico-religious ferment marked by the birth of a violent independence party, periodic anti-colonial uprisings and the regular emergence of apocalyptic preachers prophesying the end of days.

Over every aspect of Jewish life fell the shadow of the aquila, the Roman standard. The overlordship of a pagan power was felt as an intolerable religious and national affront.

Seething discontent would reach its terrible climax in the First Jewish-Roman War of 66-73CE, which left the Jerusalem Temple a smoking ruin and a million dead. Sixty years later the legions would savagely suppress another rebellion, led by nationalist general Simon bar Kokhba.

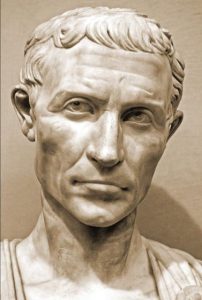

Governor Pontius Pilate

Like the British in Africa, the Roman prefect, Pontius Pilate in 26-36CE, ruled through local clients, including Herod, the puppet king of Galilee. The Sadducees, the Hellenised landed elite who controlled the Temple, were a comprador class who relied on Roman patronage.

The Romans had a monopoly on lethal force: only they could carry arms and only the prefect could execute, which he did at the first whiff of sedition. The Jews paid for the imperial administration: taxes, from which Roman citizens were exempt, were a potent grievance.

The result was a fevered millenarian climate fuelled by Old Testament prophecies of the Messiah, an earthly king of David’s lineage who would liberate the Jews and sweep away their enemies.

The Zealots, founded in 6CE, called for armed struggle; the ultra-nationalist Sicarii carried hidden daggers to assassinate Romans and their Jewish collaborators.

Pious scholars with a popular following, the Pharisees looked forward to the Messiah but were politically quiescent. Another sect, the Essenes, which included the Qumran monastic community that wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls, withdrew into ascetic seclusion to perfect themselves for the messianic age.

Some scholars believe the Essenes were linked to John the Baptist, who immersed his followers in the Jordan River in purificatory readiness for the coming of the meshiach, and who baptised Jesus.

The Evangelists scramble to underline John’s recognition that he is the Nazarene’s subaltern and precursor. But he may have galvanised Jesus’s ministry. The baptism hints at Jesus’s desire for ritual purification and acknowledgement of John’s seniority. Otherwise, why submit to it?

Elsewhere Matthew contradicts the claim that John knew Jesus was the “Anointed One”. After Herod arrested him, the Baptist sent Jesus a message asking: “Are you the one who is to come, or should we expect some other?”

Alsacian theologian, philosopher and 1953 Nobel Prize winner Albert Schweitzer believed both men were products of the first-century politico-religious ferment, apocalyptic preachers wholly dedicated to proclaiming the imminence of the Kingdom of God on earth.

But they diverged in important ways. Historian and former Catholic priest John Dominic Crossan argues that because the Jordan symbolised the boundary between Jewish exile and the Promised Land, the Baptist’s use of it deliberately evoked Joshua’s crossing and conquest of Canaan.

“Presumably God would do what human strength could not do – destroy Roman power – once a critical mass of purified people was ready for such a cataclysmic event,” Crossan writes. Certainly Herod, who beheaded him, regarded John as a political threat.

Some 19th century exegetes cast Jesus as a nationalist revolutionary, but he seems to have had no interest in a terrestrial kingdom or political change.

Wasn’t Jesus too complex for Pilate to handle?

Until he appears before Pilate, the Romans hardly feature in his ministry – indeed, he mixes with tax-collectors, reviled because they served the oppressor. In John’s Gospel he tells Pilate that his kingdom “does not belong to this world”.

His followers misread him: voicing the political dismay that followed the disaster of the crucifixion, the disciple Cleopas lamented: “We had been hoping he was the man to liberate Israel.”

Jesus’s famous rejoinder on Roman taxes – “Render unto Caesar …” – suggests he accepted taxation, but considered it irrelevant. For one who believed so strongly in the imminent “cataclysm of God’s eruption into human history”, as historian Michael Grant puts it, the Roman rule may have seemed superficial and transitory.

Crucially, Jesus also departed from the Baptist in believing that he himself was inaugurating God’s kingdom – which was a work already in progress.

Luke records him as reading from the prophet Isaiah in the synagogue: “The spirit of the Lord is upon me because he has anointed me… to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favour.” Then, with all eyes on him, he added: “Today, in your hearing, this text has come true.”

This typifies a thought pattern alien to us but pervasive in the Gospels – of “typology”, that events were prefigured in the past and foreshadowed the future.

Jesus’s arrival in Jerusalem, trial and Passion bristle with Old Testament references, and he may have contrived events to resonate in this way. His entry on a donkey – which he told his disciples to fetch – is in clear fulfilment of the prophet Zechariah.

Similarly, the typology of the “Suffering Servant” in Isaiah (“He was pierced for our transgressions… by his scourging we are healed”) apparently drove his growing conviction not just that he would die, but that he must die for his mission to succeed.

His anguished plea for “this cup to pass me by… Yet not as I will, but as thou wilt” speaks movingly of the inner warfare between his apocalyptic fervour and dread of the approaching ordeal.

The Gospels make it abundantly clear that Jesus thought the full-blown arrival of the Kingdom was at hand. He may also have come to think his own death was the providential condition for its establishment.

After vividly evoking the wonders of the Last Day – the darkening of the sun and moon and descent of the “Son of Man” on clouds of glory – he tells his disciples in Matthew that “the present generation will live to see it all”.

But there was more to his teaching than a mistaken doctrine of ends. He nowhere describes conditions in the Kingdom, but – as reflected in the Lord’s Prayer – apparently saw it as a mystical dispensation where God’s will would prevail “on earth as in heaven”.

All could enter the Kingdom regardless of rank – if they underwent metanoia, a sea-change of heart and mind. This “radical egalitarianism”, as Crossan calls it, entailed a widely accessible itinerant ministry; “open commensality”, where all ate together without social distinction; and a healing agency that embraced outcasts and the ritually unclean, including lepers and the mentally ill.

Such radically counter-cultural practices underpinned Jesus’s clashes with the religious authorities. Accused by the Pharisees of ritual pollution for consorting with sinners and tax collectors, he excoriated them as “tombs covered with whitewash” – outwardly observant, but spiritually dead.

Similar concerns may have sparked the “Cleansing of the Temple”, the last straw for the religious establishment. The money-lenders and animal sellers he rousted served the Temple’s sacrificial functions. But like Isaiah, Jesus may have felt that without spiritual renewal, “the reek of sacrifice is abhorrent to me”.

Similar concerns may have sparked the “Cleansing of the Temple”, the last straw for the religious establishment. The money-lenders and animal sellers he rousted served the Temple’s sacrificial functions. But like Isaiah, Jesus may have felt that without spiritual renewal, “the reek of sacrifice is abhorrent to me”.

The equality of the elect also implied an unusually high status for female followers. Mary Magdalene and other women provided for him and his disciples “from their own resources”, according to Luke. Four women are recorded at the crucifixion, while his male followers seem to have made themselves scarce.

Jesus’s message is presented as universal, but the Gospels strongly suggest he did not see himself as ministering to the Gentiles. This shift in focus was largely worked by St Paul, a Hellenised Jew from Asia Minor who seems to have known almost nothing about Jesus as a historical figure.

There is no getting around two Gospel passages that underscore Jesus’s strong Jewish religious identity and belief that the Gentiles were not his concern. Sending his apostles to spread the word, he warns: “Do not take the road to Gentile lands.” More pointedly, when a Phoenician woman asks him to heal her daughter, he ignores her, then growls: “It is not fair to take the children’s bread and throw it to the dogs.” He relents only after further pleading.

Some believe the call in the Sermon on the Mount not to cast pearls before swine also relates to the Gentiles. What Jesus did, however, was to plant the seed of the left-wing outlook – the idea that society has a special duty of protection towards its most vulnerable, the poor, the sick, the young and the old.

He did this by channelling the dozens of pro-poor adjurations in Isaiah and elsewhere in the Jewish Bible and transmitting them, with unique emphasis, to the emerging church – and thence to wider humanity.

Dutch scholar Peter van der Horst points out that there was no concept of special relief for the poor in the Greco-Roman world – indeed, poverty was considered a mark of a flawed character and predisposition to crime. Significantly, the first organised charity in the ancient world, initially for widows, was among the early Christians of Jerusalem.

Together with his world-negating refusal to compromise with authority, this has been Jesus’s lasting political bequest. His insistence that “the last shall be first” has had volcanic reverberations down the ages. DM/MC/ML