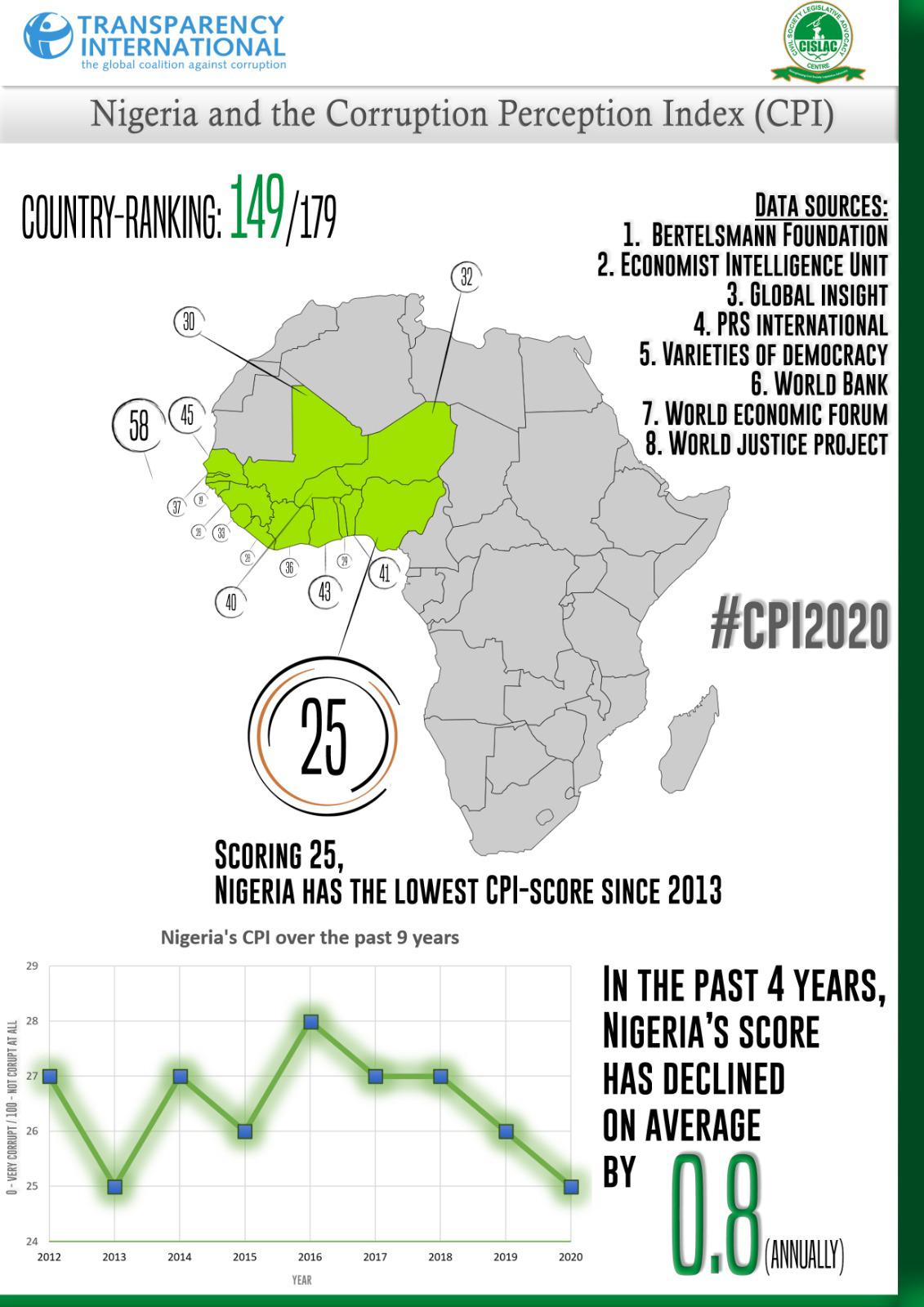

In addition to banditry, kidnapping and generalised insecurity, the magnitude of corruption in Nigeria is back in the news with the 2020 corruption perception index ranking the country worse than that of 2019. The index as released today in Abuja by the Civil Society Legislative Advocacy Centre (CISLAC), the National Chapter of Transparency International, (TI) which anchors the annual index shows Nigeria squatting at 149 out of 183 countries – three places down compared to 2019. Her actual score is 25 out of 100 points in the 2020 CPI. Again, that is falling back by one point compared to last year.

The global highlight by Transparency International on its website talks of how corruption and Covid-19 are worsening democratic backsliding. The highlight is reproduced verbatim below in this news feature.

In Nigeria, the rating will be a big image problem for the federal Government and the party in power, coming on the heels of what CISLAC and its partners in anti-corruption advocacy call numerous challenges facing the country, ranging from the Covid-19 pandemic, insecurity, high unemployment level and a sharp increase in government borrowing amongst others.

It would because another year of decline naturally interrogates the definition, principles and practices defining the Federal Government’s war against corruption. Although it is all about perception of corruption within Nigeria’s business community and experts of the realm, it matters because, in the social world, there is no distinction between perception and reality since the way people perceive things is also the way they go about reacting to it. In other words, the index does not have to bother about whether it is impartial or objective once it is called a perception index. TI is all normative, notwithstanding the multiple sources of its data.

Apparently cashing on this, CISLAC and partners are saying that “Nigeria’s CPI score is just another reminder of the need for a fast, transparent, and robust response to the challenges posed by corruption to Nigeria. It is worrying that despite the numerous efforts by state actors on the war against corruption, Nigeria is still perceived by citizens and members of the international community as being corrupt. CISLAC/TI is forced to ask why the results do not commensurate with the efforts?”

They are calling on the government and her supporters to examine the drivers behind Nigeria’s deteriorating anti-corruption image and consider actions, identifying the following weaknesses, among others:

Weakness 1: Absence of transparency in the COVID-19 pandemic response

With the COVID-19 pandemic out of Nigeria’s responsibility, there has been a lack of transparency in the emergency response of the government. Coupled with the gap in coordination, the process has been fraught by incessant flouting of procurement guidelines, hoarding of relief materials and diversion of these materials which are then used as personal souvenirs presented to political party loyalists and close associates. We find it disturbing that in some cases, supplies donated by a group of well-meaning Nigerian business persons, corporate entities, development partners and others under the Coalition Against COVID-19 (CACOVID) were left inexplicably undistributed, and in some cases rotten, by the federal and state governments. While these occurrences are not specific to Nigeria, citizens are yet to see concrete action by the anti-graft agencies on these issues.

Weakness 2: Nepotism in the public service appointments and promotions

In the past year, we witnessed nepotism and favoritism in the appointment and promotion of some public officers. For example, all Nigerians remember the controversy which trailed the decision of the National Judicial Council (NJC) when at least 8 (eight) of the 33 judges recommended for appointment by the NJC were either children or relatives of current or retired Justices of the Supreme or Appeal Courts. The Nigerian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in itself is not an exception with allegations of individuals promoted on the basis of their relationship and other affiliations as against merit and other criteria stated in the rule books. Reports around the commercialization of employment into various institutions including admission into various tertiary educational institutions put the nation in bad light. The extortion for the acquisition of services like healthcare, passports renewal and obtaining of visas creates a negative perception of corruption in Nigeria.

Weakness 3: Lack of adequate anti-corruption legal frameworks and interference by politicians in the operation of law enforcement agencies.

CISLAC/TI is not oblivious of some successes recorded by the Nigerian government such as the Transparency portal managed and implemented by the Office of the Auditor General. These activities have the potential to bring corruption and wastefulness of the government agencies at all levels to the end. We fully support this initiative.

Weakness 4: Prevalence of bribery and extortion in the Nigerian Police

The year 2020 witnessed the #EndSARS protests which saw young people across the nation demanding an end to police brutality and corruption. A factor that led to this protest was widespread bribery and extortion by law enforcement officials especially the police. The first and second national corruption surveys conducted by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in partnership with the government’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) and released in 2017 and 2019 both showed the Nigerian Police is the institution with the highest prevalence of bribery amongst the institutions measured. While there have been commendable efforts by the Police Complaints Response Unit (CRU) in reducing police abuses, there is a need to scale up the efforts of the unit to meet the demands of citizens as contained in the Police Act 2020.

Weakness 5: Security sector corruption

From violent extremism and insurgency to piracy, kidnapping for ransom, attacks on oil infrastructure, drug trafficking, and organized crime, Nigeria faces a host of complex security challenges. These threats typically involve irregular forces and are largely society based. They are most prevalent and persistent in marginalized areas where communities feel high levels of distrust toward the government—often built up over many years. At their root, these security challenges are symptoms of larger failures in governance.

As many of Nigeria’s security threats are domestic in nature, the Nigeria Police Force (NPF) is often the primary security interface with the public. However, low levels of public trust in the police inhibit the cooperation needed to be effective against these society based threats.

Nigeria’s security system is also perceived to be politicized. Leaders are often appointed based on their political allegiances rather than on their experience or capabilities in law enforcement. As a result, the quality of leadership at the helm of affairs suffers. Appointees under such circumstances feel loyalty to their political patron rather than to their institutions or citizens. How and to whom the law is applied is not consistent. Norms of professionalism and ethics are weakened.

The problem of non-meritocratic leadership is exacerbated by a command-and-control structure that is opaque, centralized, and often chaotic. Security leaders who have not earned their position lose the respect of their colleagues, who are then more likely to abandon a unit when facing an armed threat. Insufficient understanding or commitment to effectiveness among a force’s leadership often results in the neglect of training. Problems of police engagement with communities are thus perpetuated.

The continuous opaqueness in the utilization of security votes contributes to corruption perception in the country and this process must be reformed especially when we have security agencies living and working in very poor conditions. Multiple reports of police officers protesting non-payment of allowances for election duties are now seen. The result of this is the widespread kidnappings, banditry and terrorism ravaging different parts of the country.

There is a sense the above suggestions took into consideration other texts on the issue of corruption and plausible implications. Among these as contained in the statement of the partners are the World Bank’s warning while releasing its “Rising to the Challenge: Nigeria’s COVID Response” report in December, 2020. The bank warned that “In the next three years, an average Nigerian could see a reversal of decades of economic growth and the country could enter its deepest recession since the 1980s.” There is also the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) observation that Nigeria witnessed a total of 2,860 kidnappings in 2020 which was up from 1,386 in 2019. And then the Unemployment Data for the second quarter of 2020 from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) which showed that one in two Nigerian is either unemployed (27.1%) or underemployed (28.6%).

CISLAC and partners would seem to be saying: if the World Bank and the CFR are institutions with hegemonic gaze, what of the NBS? Aside from (CISLAC)/ Transparency International Nigeria, the others are the Centre for Democracy and Development (CDD) and BudgIT.

Meanwhile, from TI website is this global picture:

The 2020 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) released today by Transparency International reveals that persistent corruption is undermining health care systems and contributing to democratic backsliding amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Countries that perform well on the index invest more in health care, are better able to provide universal health coverage and are less likely to violate democratic norms and institutions or the rule of law.

“COVID-19 is not just a health and economic crisis. It is a corruption crisis. And one that we are currently failing to manage,” Delia Ferreira Rubio, Chair of Transparency International said. “The past year has tested governments like no other in memory, and those with higher levels of corruption have been less able to meet the challenge. But even those at the top of the CPI must urgently address their role in perpetuating corruption at home and abroad.”

Global highlights

The 2020 edition of the CPI ranks 180 countries and territories by their perceived levels of public sector corruption, drawing on 13 expert assessments and surveys of business executives. It uses a scale of zero (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean).

Denmark and New Zealand top the index, with 88 points. Syria, Somalia and South Sudan come last, with 14, 12 and 12 points, respectively.

Significant changes

Since 2012, the earliest point of comparison in the current CPI methodology, 26 countries significantly improved their CPI scores, including Ecuador (39), Greece (50), Guyana (41), Myanmar (28) and South Korea (61).

Twenty-two countries significantly decreased their scores, including Bosnia & Herzegovina (35), Guatemala (25), Lebanon (25), Malawi (30), Malta (53) and Poland (56).

Nearly half of countries have been stagnant on the index for almost a decade, indicating stalled government efforts to tackle the root causes of corruption. More than two-thirds score below 50.

COVID-19

Corruption poses a critical threat to citizens’ lives and livelihoods, especially when combined with a public health emergency. Clean public sectors correlate with greater investment in health care. Uruguay, for example, has the highest CPI score in Latin America (71), invests heavily in health care and has a robust epidemiological surveillance system, which has aided its response to COVID-19 and other infectious diseases, like yellow fever and Zika.

In contrast, Bangladesh scores just 26 and invests little in health care while corruption flourishes during COVID-19, ranging from bribery in health clinics to misappropriated aid. Corruption is also pervasive in the procurement of medical supplies. Countries with higher corruption levels also tend to be the worst violators of rule of law and democratic institutions during the COVID-19 crisis. These include Philippines (34), where the response to COVID-19 has been characterised by major attacks on human rights and media freedom.

Continuing a downward trend, the United States achieves its worst score since 2012, with 67 points. In addition to alleged conflicts of interest and abuse of office at the highest level, in 2020 weak oversight of the US$1 trillion COVID-19 relief package raised serious concerns and marked a retreat from longstanding democratic norms promoting accountable government.

Recommendations

The past year highlighted integrity challenges among even the highest-scoring countries, proving that no country is free of corruption. To reduce corruption and better respond to future crises, Transparency International recommends that all governments:

- Strengthen oversight institutions to ensure resources reach those most in need. Anti-corruption authorities and oversight institutions must have sufficient funds, resources and independence to perform their duties.

- Ensure open and transparent contracting to combat wrongdoing, identify conflicts of interest and ensure fair pricing.

- Defend democracy and promote civic space to create the enabling conditions to hold governments accountable.

- Publish relevant data and guarantee access to information to ensure the public receives easy, accessible, timely and meaningful information.