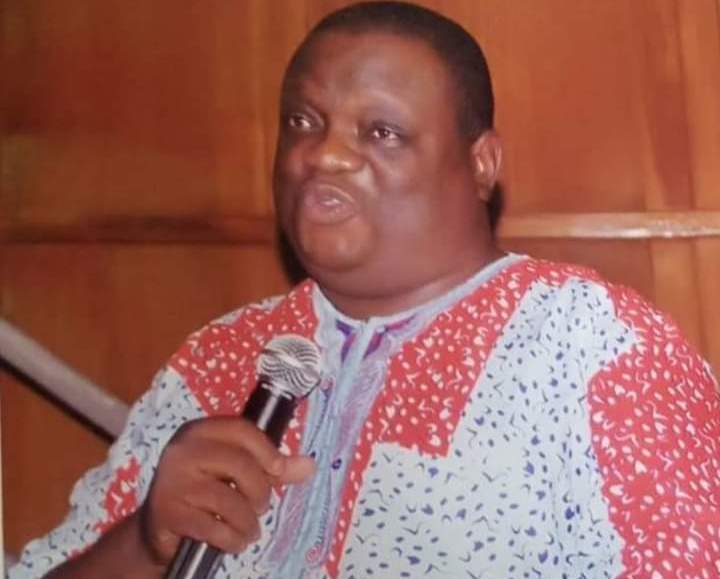

There are signposts of a tendency sense of loss in the demise of Didi Adodo, a trade unionist who was claimed by no other nightmare than Covid-19 early Tuesday, January 12th, 2021. The tributes are still pouring from across various spaces of the radical ferment in Nigeria towards his burial January 13th, 2021.

But, if memorials are for the living rather than for the departed, then the group sense of loss of Adodo must take a genealogical character. In that case, his appearance in Bayero University, Kano in 1986 must be the starting point. he was there from the University of Benin detachment of the student movement. That was a fundamental moment of crystalisation of the defunct National Association of Nigerian Students, (NANS) as successor of the National Union of Nigerian Students, (NANS). It was so because that was the convention the late Emma Ezeazu was elected president of NANS. The Ezeazu tenure in NANS marked the era the Nigerian State took on radical students’ activism with cultists violently contesting the campuses with NANS activists. The country is still reeling from that as the phenomenon has grown beyond the campuses into the larger society.

A big labour loss

There is also something interesting that less than a decade or so later, Kano could not perform a similar ritual of hosting an elective convention of the same NANS. Instead, a gang of students of the same Bayero University, Kano took it upon themselves to make the convention impossible on that campus. And they ‘achieved’ that mission. Kano had changed. But it was not Kano that had changed. It was just that anyone who invoked ‘Allahuakbar’ in the Kano environment had a smart strategy. The smartness there is how the phrase has a demobilizing force on those who would ordinarily not have supported those invoking it. Instead, the phrase also makes it impossible for such people to rise against those misusing the phrase. In truth, it was the government in power at the centre which felt so insecure it prodded some elements in the university to look the other way as the gang unfolded.

Every major actor in the university knew this. Even the leaders of the radical student movement knew this ahead of the assault and contemplated their own plausible responses. The violent nature of the main response forced dropping it. From the benefit of hindsight, it would not even have been implemented. The DSS would have arrested as many of the leaders of the radical student unionists long before the H-hour. This became known a year or so later when it turned out that the incumbent president of the Student Union Government at the time left the NYSC straight into employment with the DSS. Shuo! What it means is that if the suggestion had been democratically endorsed at what used to be called the ‘inner caucus’ of the radicals, it would not have taken more than an hour for the DSS to know and to move. There is absolutely nothing wrong in proudly working for the DSS but why does anyone have to humiliate himself by posing to be a radical activist when he is not? Well, people do it, even in the radical student movement.

It is in that sense that Adodo is a reminder of the long night of the ‘violent turn’ that led to where Nigeria is today. And as the late Reuben Ziri, ABU, Zaria image breaker in Historical analysis, was used to saying, you cannot expect democracy in the morning of such a long night. The foregone might provide the sense of loss in union circles about Didi Adodo. He remained on course. The records show that, at critical moments, he reminded himself of the spirit of Kano 1986, remaining faithful to it. Each time he did so, he was able to overcome opportunism. One example must be him leading the group that returned to the mainstream NLC from attempting a breakaway at some point even though as the General Secretary of the group, he could have had life more abundant. It seems that, for him, it was never just about being called a radical but about making every temptation a turning point in the never ending struggle to be a better human being and doing so imaginatively.

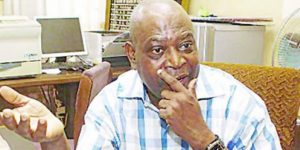

The late Prof Iyayi

This is probably not surprising for a student who lived in the late Festus Iyayi’s Boys Quarters at the University of Benin. Time has conferred a much bigger worth on Festus Iyayi, an individual who could in just few paragraphs, set out a manifesto for a country. Just in case this has faded out of memories, it might be worth a recap.

Speaking at the 50th birthday anniversary of the then General Secretary of the Nigeria Labour Congress, (NLC), Iyayi said, inter alia:

In many parts of the world, individuals feel specially honored if their day of birth falls within the halo of some significant national or historical event: the day of the revolution, the day of the declaration of independence, the day of man’s landing on the moon, the day of freedom for Nelson Mandela. Following this, all those who are about to mark or are actually marking their 50th birthday in Nigeria ought to have their noses in the air. … The achievements of the nation ought to be part and parcel of the development of those who are about to or have just attained 50 years of age. …Thus this address ought to be devoted to themes like “Responding to Nuclear Threats: The Role of Nigeria’s New Missile AF50”, “Retaining Nigeria’s Leadership in Car Manufacturing: Keeping the Japanese Behind”, “Sharing Nigeria’s Cure for Malaria with the World” or “Teaching the World How to Dance: Lessons from Nigeria’s Democratic Success”. Unfortunately, the story of Nigeria at 50 is such that not only can we not devote ourselves to such themes, we find that our individual lives have been diminished by the dismal failure of the country to realise its great potentials”

It is possible that Iyayi too might have been talking a lot but, like everyone else nowadays, saying nothing in effect. But he is not here anymore and History has thus excused him from complicity in the current murmuring about Nigeria. What we know is that, up to his last moment, he was speaking to the elusive Nigerian moment in an uncommon manner, in uncommon terms. Automatic connections can be problematic but inferring a strong linkage between the Iyayi radius and the Didi Adodo track might not be outlandish. At each turn, from Kano to labour politics, he reminds fellow compatriots of one moment in the journey to restructuring.

May Didi Adodo go well but not without his death being such a powerful reminder to the Chiemekes, the Otives, the Ogagas and the whole lot of the UNIBEN detachment on the UNIBEN flavour of speaking power to truth, (not the other way round because truth is always the problem, not power)?