Those who think former colonial powers are no longer pressing direct buttons in the affairs of their ex-colonies would have to think twice. A former Deputy High Commissioner of Britain to Ghana, Ambassador Craig Murray, is spilling the beans on what he, of course in the name of Her Majesty, did in the 2000 elections in Ghana, as recently as 20 years ago.

His Excellency, Craig Murray

Among others, the top diplomat and two other Members of the British Parliament were the influence on the government of the National Democratic Congress, (NDC) from closing down and taking over the FM Station, Joy FM, using the military. Or from the taking over of Afari-Gyan’s family hostage. Afari-Gyan was the Chairman of the Electoral Commission of Ghana then. Also in the book are the stories of the threat of a military coup; how Indian Ink was brought in on a Chartered private Jet for the run-off election; the extensive ties of the Brits with key players in politics and civil society; the outsized role of Mrs Rawlings.

The book is out but not in the public sphere yet. But an extensive extract which is not exclusive to Intervention is, however, available And it shows to the minutest details of a British Deputy High Commissioner getting involved to as far as threatening to arrest fraudulent voters in one voting space or another; bringing in indelible ink for a subsequent round of elections, collating faxed copies of the results with the Chief Electoral Commissioner and coordinating strategies with the opposition on responding to the outcome of an electoral contest.

How generalisable the specific case of Ghana is remains debatable. It would not be surprising if it is absolutely the same pattern that plays out in most elections across Africa in terms of how decisive foreign powers could be, sometimes as the only bulwark against stalemate escalating to imponderable consequences but, at other times, for something else. In all cases, the pattern speaks to something about the hollowness of the sovereignty that students of International Politics bother themselves no end even when something else is playing out in the background.

It is a long read but an interesting read, especially what it shatters: the narrative of the Ghanaian political establishment as working by a ruling class consensus that knows how to refrain from self-destructive antics typical of politicians elsewhere. This report will be updated as soon as the name of the book is confirmed.

The Excerpts:

To return to the Ghanaian election in 2000, it would be foolish to deny that there is a tribal element in voting in Ghana. The Ewe vote overwhelmingly NDC, the Ashanti overwhelmingly NPP. The significant swing is among other smaller tribes. But then, it is foolish to pretend this is uniquely African. Look at an electoral map of the United Kingdom. The Scots and Welsh vote overwhelmingly Labour, the South East of England votes Conservative. Celts have a higher than average propensity to elect Liberal Democrats. Is all that tribal? Yes, up to a point, Ghanaian voting is tribal up to a greater point. But there are other social and economic factors at play, too.

“In Ghana as in the UK, it is a matter of the community that you feel embodies and protects your individual interests, and a collective view or consensus within that community, on how best to take forward the interests of that community.

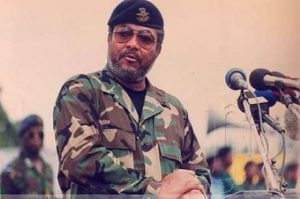

Rawlings managed to escape transition to anarchy but thanks to the Brits?

“Nor was electoral fraud limited to the NDC. It was simply that, as the party in power, they had more opportunity. In fact there were different methods of fraud prevalent, with the Ewe areas going for multiple voting, while the Ashanti rather favoured under-age voting. The Electoral Commission had to guard against both.

“One key weapon was indelible ink. When somebody voted, their thumb was painted, it is difficult to find an ink that is truly permanent, and DFID, who were paying for it, found India to be the only source of an ink that truly could not be washed or rubbed off. (Hence the term Indian Ink, which is what permanent markers were called when I was a child).

“This special ink was applied with a little plastic tube that was rubbed inside the nail, where it joins the skin, to make it hard even to sandpaper the ink away.

“Election monitoring abroad by EU member states normally comes under the purview of the European Union, but the EU reached the rather extraordinary conclusion that Ghana was a mature democracy and monitoring was not necessary. Ghanaian civil society had mobilised to provide a number of formidable monitoring organisations, as Ghana’s middle class asserted itself. It managed to persuade the FCO to provide three experts from the Electoral Reform Society for several weeks in the run-up to the election, with a further team of volunteers for the voting itself. I was delighted that these included my old friend, Andy Myles, Chief Executive of the Scottish Liberal Democrats and a veteran of these monitoring missions worldwide.

“There was a scattering of other European observers. For the poll itself we effectively closed the High Commission and sent almost all our staff, local and diplomatic, around the country to observe the poll. A few staff were also lent by other EU missions, who consented to put the ERS team in charge of the organisation of the whole effort. The ERS team carried out training and allocated the staff, in teams of two, to different regions around Ghana, with instructions to tour the polling stations ensuring all was in order, ballot boxes were sealed, ballots checked, ID shown etc.

“A further valuable addition were two British MPs, Roger Gale and Nigel Jones, who came out under the auspices of the Inter Parliamentary Union. Their prestige with Ghanaian parliamentarians was a great help to our effort.

“The United States did their own thing. This included, in what seemed to me an absurd example of political correctness, sending a delegation of blind elections observers. In any event, as the Ghanaian elections followed immediately upon President Bush’s fraudulent election, the US had no credibility on the issue.

“Votes were counted in individual polling stations, and then the results sheet, signed by the polling station officers and local party representatives, would be sent to a constituency centre for collation, together with the sealed ballot papers themselves. In the constituency centres, constituency results would be tallied, declared by the returning officer, signed off and sent to the regional centre. In the regional centre they would be verified, and then faxed to the Electoral Commission Head Quarters in Accra. We had supplied the fax machines, and back-up satellites telephone systems.

“Once polls had closed, our monitors would follow the ballot boxes through the stages, until they all reached the regional centres. They would then telephone the results through to me at the Electoral Commission HQ so I could check the fax eventually produced at HQ against the result declared in the region. It was at this stage that most of the fraud was to occur in the 2007 Kenyan and Zimbabwean elections, where vigilant local observers ensured accurate local results, but they were altered at the centre. We had independent international verification of every regional result before it arrived at the centre, where it was I who was actually taking it off the fax and moving it to the collation, so there was no opportunity for fraud.

“The issue of photo ID cards brought perhaps the startling example of people power in recent African history, exercised above all by the women of Ghana. Alarmed that they were going to lose a fair election, the NDC government brought a case against its own Electoral Commission to seek to have the photo ID card system declared illegal, on the grounds that it disenfranchised legitimate voters. I knew this to be nonsense, but ever since sitting High Court judges had been murdered, High Court judges were reluctant to oppose Rawlings, and they ruled against the Electoral Commission and the ID card system, despite the mass demonstrations around Accra chanting “No ID No Vote”.

The normative power

“It appeared I had wasted £10 million of DFID money on the photo ID scheme. But I had seen two things from the court case. One was the courage of the Electoral Commissioner, Kwadwo Afari-Gyan, in being, prepared to stand up to the bullying government. The second was the popular demand for the photo ID cards.

“The people now took over. The polling station officers, all over the country, who had supervised the issuing of the photo ID cards, decided they were going to use them, whether the High Court wanted or not. These were local school teachers and bank or post office managers, and it was a quiet, middle class revolution. While the voters themselves, as people queued to vote, were checking the others in the queue and kicking out anyone without a photo ID. This movement was led, everywhere, by Ghana’s formidable female market traders. This popular adoption of the Photo ID system was common throughout the entire country, even in government areas: and in most of the country spontaneously supported by the local police.

“After myself inspecting polling stations all day, I entered the Electoral Commission on the night of 7 December, and carefully monitored the collation of the first round results. A more or less uniform swing to the opposition across the whole country was soon obvious, and my phone ran hot as results were telephoned in to me from the regions. There were just a very few suspect constituency results, in Brong Ahafo and Northern regions, sharply in conflict with the national trend, but 98% of the constituency results rang true. It became obvious that the opposition was heading for a small parliamentary majority, while no candidate would exceed 50% in the Presidential election, leading to a run-off. When the votes were finally tailored, John Kufuor had 48.4% against John Atta Mills 44.8%.

“The NDC had woken up too late to the fact that they could not win a legitimate election. They had then made clumsy and unpopular steps to try and prevent a legitimate election. The failed attempt to thwart the voter ID scheme was one example. They also tried to move against FM radio when it was far too late.

“On the evening before the poll, I was taking Roger Gale and Nigel Jones to visit Joy FM, possibly Ghana’s most influential radio station, run by my good friend, Sam Attah Mensah. We were sitting in the back office of the station when an armed possess of Rawlings’ security men from the castle came in the front door and announced that they had come to close down the radio station on the President’s instructions.

“I appeared from the office and said: ‘Good evening. I am Craig Murray, Deputy British High Commissioner, and these gentlemen are Mr. Roger Gale MP and Mr. Nigel Williams MP, members of the British Parliament who are here on behalf of the Inter Parliamentary Union”’.

“Roger Gale then added: ‘Obviously there has been some mistake. I thought I heard you say that you were closing down the station, but we are here to visit our fellow democracy, Ghana, and democracies don’t close down radio stations”.

“Nigel Williams then chipped in: “It must be a misunderstanding. Perhaps you can go back and ask for more instructions?”’ “The goons, thwarted by this unexpected manifestation of the British Parliament, left in some confusion. Joy FM never was closed down. We returned to our tea, and Sam opened something a bit stronger to celebrate.

“I had been able to predict the results of the first round with some accuracy, having spent the past year travelling all around Ghana and speaking to Ghanaians of all ranks in both cities and villages. I had also formed a view of how many people had changed their vote since the election. It was very obvious to me that the substantial change in Kufuor’s vote – up from 39.6% in 1996 to 48.4% in 2000 – was more due to our reducing fraud than to a change in real votes cast. Put another way, I estimate the NDC cheated in 1996 by around 7% of the votes net (i.e. they cheated more than that, but some was cancelled out by cheating the other way). I am satisfied we reduced cheating in 2000 to under 2% net. A fair election is one where the margin of victory is greater than the margin of cheating – you can hope for no more than that.

“Electoral fraud is everywhere. The glaring Bush 2000 election, with myriad black voters turned away from the polls and some very dodgy electronic voting machines, was no example. I was myself to encounter more electoral fraud in Blackburn than I ever did in Ghana.

“With the second looming, the NDC started to think that I was a part of their problem. They assigned a secret service team to follow me everywhere, which must have been very boring for them. Sam Jonah came round for a drink one day and remarked that the agents who used to shadow him had disappeared around a week earlier. Now he knew why – he had just spotted them all lurking around my gate. With my driver Peter I used to go for long pointless drives, because the security services had never been given enough money for petrol. We also used deliberately to go places our 4DW Mitsubishi Montero could go, but their saloon cars couldn’t.

“Rod Pullen, the High Commissioner and my boss, was also getting a bit alarmed that we were in too deep. He saw dangers that we could be accused of rigging the election if Kufuor won, or that if Mills won, the NDC might be vindictive against us for our strictness over the elections. But Rod was still new in Accra, and I still had influence with African Command of the FCO, and strong support from Clare Short. Anyway, the die was now cast.

An electoral actor

“DFID had to find more money to help fund the second round of voting on 28 December. 16 million ballot papers had to be printed and distributed. Word was reaching me from many sources that the NDC was planning to increase its vote in Volta Region – which it called its “World Bank” as it was so safe – by a big effort on multiple voting. Minibuses and pick-ups were being assembled to bus voters around from booth to booth.

“Our chief weapon against multiple voting was the Indian ink, but there was not enough of this for a second round. DFID had therefore bought more, but it had to be specially made, and the batch would not be ready until 24 December. With the election on 28 December this was cutting it very tight, and we found that we would have to charter a private plane to get it to Ghana. Chartering an inter-continental private plane to set off on the evening of Christmas Eve was more easily said than done. I also had no budget and no way of getting one, Whitehall having gone into festive mode, so I took a chance on using the Embassy’s own local budget pending a resolution. Yes, that ultimately got me into yet more trouble.

“The government plainly from various actions did not really want the Electoral Commission to get the India ink, and I was most concerned that it would get delayed by Customs. That is why, on Christmas Day 2000, instead of eating my Turkey I was baking on the heat of the tarmac at Kotoka airport. When our plane taxied in, we quickly unloaded the boxes of little ink bottles straight onto two trucks. I escorted these straight out of the VIP lounge gateway, helped by a substantial Christmas tip to the guards. The truck drivers then set off around Ghana, taking the ink to the regional centres for onward distribution to the constituencies. I spent Christmas evening briefing election observers; that sounds crazy, and it says something extraordinary for the spirit of those times that we had 100% attendance of observers on a purely voluntary basis. I remember Fiona, herself an observer, striding through the volunteers distributing Mince pies, and Andy Myles making a number of serious and valuable points while wearing a silly paper hat.

“As for Roger Gale and Nigel Jones, I cannot speak too highly of them. We British have a pretty scathing view of our MPs, and often it is justified. But while it was one thing for these MPs to come out in early December, it was quite another for them to give up their holiday and come out again between Christmas and New Year. Frankly, I had not expected it. Nobody could say that this trip was a jolly, or even comfortable, and they certainly both dived into the field and worked hard. Their presence undoubtedly was one of the small factors that combined to tip the scales in favour of a successful democratic transition.

“It had been a major pre-occupation for some time to find a retirement role for Jerry Rawlings that he would feel commensurate with his dignity, and which would thus encourage him to give up power and move on. The UK had been making discreet soundings in the United Nations and other international bodies to try to initiate a tempting proposal that could be put to him. Our efforts were hampered by the widespread international perception that Jerry Rawlings was off his rocker, while the fact that he had been a military dictator who had executed (among others) his predecessor meant that we could not automatically count on support even from EU partners. ‘He hasn’t murdered anyone for a while’ is not the most compelling of arguments. In the end we decided that it looked like the best that might be done was some sort of roving UN Ambassador status on HIV awareness and malaria prevention, which might utilise his undoubted charisma and ability to communicate with Africans.

“One of the problems of history is that there is a tendency to see whatever occurred as inevitable, whereas there may have been in truth a whole range of possible outcomes, with tiny factors tipping the scales. Nowadays people tend to take the view that Ghana’s transition to real democracy was natural and easy. Some even measure Ghana’s democratic era from Rawlings’ 1992 plebiscite.

“But in fact in 2000 nobody could be sure how Rawlings would react to losing power. The NDC had no shortage of hotheads like Tony Aidoo and indeed Mrs. Rawlings – normally so influential over her husband – who wanted to react to an NPP victory with a military takeover and claim of electoral fraud. Rawlings held a meeting in a hanger at the military base of Burma Camp to judge the reaction of the army to a possible takeover. He spoke of the dark forces threatening to usurp the country. My sources in the meeting told me that the soldiers became restless, and some even started to drift away as Rawlings was speaking. But he had the security services and some military units still undeniably loyal to him, particularly his notorious Commandos”. Certainly at Christmas 2000 nobody was ruling out a military coup.

“There was even a very real danger of civil war. The Ashanti, who had been the dominant political force for centuries, were furious at what they saw as the stolen elections of 1992 and 1996. If they were excluded from power again, there was a real danger that Kumasi, Ghana’s most teeming and vibrant city, would explode into violence. In 2000, Ghana by no means felt safe from the spectre of violent conflict. Every Embassy was dusting down and updating its emergency consular evacuation plan. Once again I found myself slap in the middle of a game being played for the highest possible stakes.

“Our election monitors dispersed again around the country. I saw the head of our commercial section, Malcolm Ives, depart for the North with his wife Sue, looking like they were off for a picnic, with straw hats, hampers, and even that most English of facilities, a windbreak. The result of the second round of voting was a foregone conclusion. Kufuor’s first round lead had destroyed Rawlings’ aura of invincibility. I spent election day in Volta region, looking for evidence of multiple voting. I found a couple of minibuses full of young men who were plainly engaged in multiple voting. They all had traces of India ink on their thumbs which had plainly been sanded off. A couple of [them] were actually bleeding. I told them they were under arrest and to go and report to the local police station. Rather amazingly, in both cases they actually did this, although I was only bluffing, having no authority at all.

“That evening with Peter at the wheel we raced back through the darkness to Accra, for me to take my place at the Electoral Commission. It is on a small back street near Ridge. I found both entrances to the street blocked off by soldiers. They said they were there to guard the Commission, but this seemed to me ominous. There was a definite tension in the Electoral Commission that night which had not been so obvious in the first round.

In self-recognition

“Slowly, from around 1 am, constituency results started to come in. There wasn’t much movement from the first round, but there was a slight additional and more or less consistent swing to Kufuor. You could have cut the tension with a knife. Party representatives came in and out, checking on what was happening. The Electoral Commissioner, Kwadwo Afari-Gyan, was the coolest man in Ghana that night. He and I sat in his office, collating the master register of the faxes from the constituencies and personally checking the addition of the votes. When there was a pause, we would stop for a beer and discuss how the election was going.

“Kwadwo’s phone kept going, and after a while it became clear that he was getting a whole string of threatening phone calls from the Castle, instructing him to fix the result. He replied very calmly: “The result will be what the result will be. I am just making sure it is fairly counted. I have no influence on the result”. It became his mantra.

“Then, suddenly, taking his umpteenth phone call, he stiffened. He summoned me to his side to listen. It was his wife. Soldiers had come to their bungalow, taking Kwadwo Afari Gyan’s wife and children hostage. They were threatening to kill them if he did not deliver the “right” result. As the pressure on him had mounted through the night, the only sign of stress that Kwadwo had given was to smoke faster and faster. Now he barked down the phone.

“Put their leader on”.

“A soldier quickly took the phone, and started repeating the demand to Kwadwo. Kwadwo interrupted him. It is very taboo for Ghanaians to swear, so I have edited what Kwadwo said:

“Listen you little *****. Do you think you soldier boys can still tell us all what to do? How dare you come to my house and threaten my wife and children. I am sitting here with the British Deputy High Commissioner, and he knows what is happening. Now get the ***** out of my home before we have you thrown into jail”.

“There was a short silence, and then the soldier said “Yes sir, sorry sir”. Kwadwo then told his crying wife not to worry; and turned calmly back to his work as though nothing much had happened”. (Remarkably, this story of the Electoral Commissioner’s family being held hostage by the military has never become public. Kwadwo is not the kind of man to tell it, and I was the only other one there. Ghana has never given Kwadwo all the honour he deserves. I called on Kwadwo in February 2008 to confirm that my memory of this is correct. He confirmed that it is).

“Two other unwelcome developments had started to happen. The first was armed soldiers appearing inside the Electoral Commission, not actually doing anything wrong, but just intimidating by their presence. I kept throwing them out. The second was that for the first time we started to get some apparently altered duplicate constituency results turn up. I had our observers phoning in the results, and these always tallied with those arriving on the main fax. But one or two different results from the same constituencies then started to follow, brought in by Afari-Gyan’s Deputy, Mr. Kanga. It was not necessarily Kanga’s fault, but it was he who happened to bring them in. I started to keep a jealous physical guard of the authentic results to avoid substitutions, and as the second night of the count moved into its early hours, I had been awake solidly for over three days, so I stole a couple of hours sleep with my head on the faxed originals of the election results for safekeeping. It is that image of me that has found its way into Ghanaian popular mythology.

“I awoke again the early hours, because we were now moving to the white heat of the crisis, and my mobile phone was constantly ringing. By 3am on the second night there remained only two remote constituencies still to declare. Afari Gyan and I calculated that, even if every eligible voter in those two constituencies voted for Professor Atta Mills, John Kufuor could still not be beaten. Kufuor had been elected President. But Kwadwo Afari-Gyan was not legally entitled to make the declaration until all results were in.

“This was now or never for the NDC; if they were to launch military action against the result, it had to be now. And my contacts were calling from all over Accra, giving me details of the movements and the sayings of key NDC figures and senior army personnel. There was undoubtedly a faction in the NDC that was looking to what could be done to cancel the result by military action.

The tragedy of the intellectual as electoral umpire in Africa?

“At the same time, Kufuor and his people had become highly nervous. Why was the result not being announced? Were fraudulent results being prepared? Was it going to be stolen again? Was there a delay to enable the military to prepare? The NPP General Secretary, Dan Botwe, was pressing hard for a declaration. Then, around 3am, I received two pieces of news about the same time. Kufuor, on the advice of his key advisers including Hackman Owusu Agyemang, was going to declare himself President. Almost simultaneously the NDC had decided that, in the event that Kufuor declared himself the victor, they would denounce it as an unconstitutional coup and move in the military. Just at this time I also received a firm order from Rod Pullen; he had heard that things may be going pear shaped, and ordered me to leave the Electoral Commission building.

“I phoned Hackman:

“Hackman, I heard you are going to declare victory”.

“Well, it looks like we’ve won, and…”

“Hackman, please, listen to me. Do not declare”.

“But it’s been…”

“Please, Hackman, I beg you. Tell John. Tell him from me, personally, that Craig says he has to trust him. Do not declare. Then come to the Labadi Beach Hotel. I will see you there in half an hour”.

“OK, Craig, I’ll try”.

“Devonshire House was being watched, and I didn’t want Hackman being seen scuttling around there in the early hours. With some of Rawlings’ crew’s anti-British views, that might itself have been enough to spark a coup. I shook hands with Afari-Gyan, and as I left the Electoral Commission, a squad of soldiers were coming up the stairs, guns carried rather than shouldered. I yelled at them that soldiers were not allowed inside the building, they could guard it from around the perimeter. Then I drove them before me down the stairs, and ordered the old man at the entrance to padlock the gate. So at 4am the bar of the Labadi Beach Hotel became my HQ with George Opata joining me, Peter shuttling messages all over Accra, and Roger Gale and Nigel Jones adding weight when I needed (they were living in the hotel and extremely sporting about being dragged out of bed).

“Hackman arrived and I explained to him urgently that Kufuor had, undoubtedly won. I told him that I absolutely guaranteed that Afari-Gyan would announce the true result when all constituencies were in. But I also knew that forces in the NDC were poised for a military takeover if Kufuor made an “Unconstitutional” early declaration.

“The big problem is that, although I am a big fan of Afari-Gyan, the NPP were not, viewing him as the man who delivered the fixed 1992 and 1996 results. But I had seen that he could be both brave and honourable, given the resources and support. Finally I persuaded Hackman to trust Afari-Gyan, and the NPP did not make a premature declaration. The most dangerous moment had passed.

“I then concentrated on encouraging a wide variety of respected and senior elderly Ghanaians to send messages to John Atta Mills conceding defeat. Atta Mills is an honourable man, and he did concede, to the absolute fury of Mrs. Rawlings. Mills thus killed off the chances of a coup.

“This all cleared the way for the formal declaration, made about 3pm, with Roger Gale and Nigel Jones supporting Afari-Gyan. I sat in the next room, enjoying a quiet beer. Then I went home and slept, completely exhausted.

“On the Sunday afternoon, I drove round to the home of President-Elect Kufuor. We were both in short and T-shirts, and we sat in his garden with our sandalled feet up, drinking Chivas Regal and discussing plans for Ghana in the coming year.

“After a whole generation of rule by Rawlings, Ghana had come through to genuine freedom and democracy. An African country had shown that real democracy was possible in Africa, with a change of power to the opposition after a good debate and a peaceful election. This was really the kind of progress I so desperately wanted for Africa. And I had helped to do it”