That any society in which the highest bidder is always the winner must, sooner than later, pay a price for that is, unarguably, the second of the two messages COVID-19 pandemic has sent to a country such as Nigeria. The first of the messages is the unbelievable deterioration of the stateness of the state as can be seen in the scarcity of imaginative flair, crisis of doctrine, lack of creativity in policy leading to copy-cattish disposition and the abject lack of capacity to implement anything satisfactorily. Hence the over reliance on media appearances liberally obliged state officials by an ever indulgent national media. In other words, there has been a progressive diminishing of the notion of the state, a decline that has not been noted beyond our criticism of successive individual leaders. Transcending that should be a lesson from COVID-19 as a condition of possibility for Nigeria hopefully making it to the top ranking status that the world has ever since independence retained for it.

Nigeria’s best in COVID-19 infrastructure, for instance

Another showcase from Lagos State and the most sophisticated Nigeria can boast of in this regard

Those who would insist that infrastructural bareness should be classified as a distinct message from COVID-19 may not be totally off the mark but the question would be that of what accounts for the bareness. The answer cannot but be the lack of a power elite with the ability to conceive development as a holistic process and to supervise such towards rapid social transformation as we have seen in East Asia and some parts of the Middle East. If that is correct, then the first source of infrastructural bareness in Nigeria that COVID-19 brutally exposed is the disappearing state mentioned earlier. The second source of the bareness can also not be anything other than corruption. This is because, in spite of imperialism and whatever, nobody denies that Nigeria earned relatively huge rents over the decades. If such has not amounted to a fascinating infrastructural testimony, then it must be that the revenue generated was substantially looted.

While thinking about rebuilding the state into an intelligent space of power rather than the unthinking and irresponsive domain it now is, taking another look at the anti-corruption sphere becomes equally worthwhile. This is particularly so if doing that helps to clean-up the aporias, apologia and silences observable in the anti-corruption imaginary in Nigeria.

Pointing at silences and evasions has never left the personal and professional lens of many Nigerians except that anti-corruption enthusiasm in Nigeria has since fallen victim to the spectacle of fly-by-night elements posing to be what they are not. This has been worsened by the outcome of the ascendancy of such characters and the associated lack of creativity which we can see in the limited successes of the models for taming corruption. These are naming and shaming as well as imprisonment of offenders while opprobrium for Nigeria at the global level is the collective punishment for all of us. We can speak of limited success in the sense that there is absolutely no deterrent outcome from all the naming and shaming or imprisonment that have taken place when measured against the volume and the brazenness of corruption today. It must then be clear to everyone that certain things must be wrong or simply out of sync. What could they be?

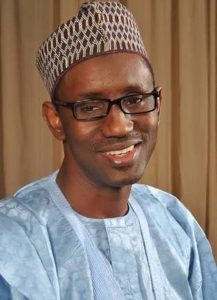

Mallam Nuhu Ribadu, practitioner of ‘high impact’ strategy

The late Justice Mustapha Akanbi

When then President Obasanjo was told in 1999 that the codes underlining prosecution of suspected offenders were sociologically incompetent, he said that was nonsense, adding that there was nothing that Nigerians did not know about corruption and that what was needed was punishing the offenders. It was much later that it was discovered that most of the provisions of such laws were simply too antiquated to be used to secure conviction of those charged before it because of what the late Justice Mustapha Akanbi subsequently called “legal obstacles to retrieval”. The law that could indict a first class developmentalist and the builder of modern Kano such as Audu Bako just for allegedly using his position to secure a bank loan could suddenly not even reprimand those in theft of billions in Nigeria nearly 40 years after.

Instead of then going back to the point of updating the laws, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission, (EFCC) bought or overemphasized its strategy of ‘high impact’ cases, a rather political technique. Subsequently, anti-corruption politics in the Fourth Republic got entangled in charges of selectivity and persecution along party, religious and regional lines.

President Buhari came in 2015 with the same presumptions: philosophers have interpreted corruption, the point is to punish offenders. Buhari was obviously in acceptance of late General Victor Malu’s point that the error in Buhari’s superintended trial of politicians in 1983-84 was in not making the trial a television show and that if that were the case, many of the politicians today would not have had the courage to go to their local communities. So, the president continued with all cases already in court. In other words, the president was not too keen in the argument that the war is beyond “moral repulsion against a ghastly manifestation of a sick system” but whose dialectics could become a political weapon used to destroy the credibility of the government of the day. That is exactly what has happened in the last few years.

So, the assumption that anyone who doesn’t know or doesn’t accept that corruption is bad must be corrupt or is a supporter of corruption has been a problem since 1999. But does such an assumption make sense in a country of several ancient empires; deep class differentiation and sundry senses of what might be called corruption in a nation-state still being built?

Second, why does this war fear inputs from the people which would have implied some mobilisation? Mass mobilisation has been excluded from the menu, denying the war of the rootedness in popular psychology that would have provided the bulwark against ‘corruption fighting back’. In the absence of that, the people have had to bear the consequences of what the Buhari regime loves to call ‘corruption fighting back’ here and there. The people’s way of explaining themselves in relation to corruption could have been used to re-validate, moderate or strengthen existing doctrines, models and tactics. That has not happened on any serious or systematic scale, possibly because non-traditional politicians such as Obasanjo and Buhari feel more secure with they being referential in the fight against corruption than the system or the party in power or the government they head being cited.

In this context, engaging with the concept of corruption towards a contextually more sensitive framing was lost or excluded. At the moment, everyone is jumping about with nothing more than what the World Bank in particular says corruption is: use of public office for private gain. It is the usual binary reasoning on such issues. The drawbacks are obvious. For instance, what happens when a private law firm, a businessman or some powerful women around town who are not in public office succeed in bending the public interest to his, her or their own will, especially in situations that do not involve financial transactions bordering on money laundering? That is one of the big silences in the conceptual framework being used.

The late Mallam Adamu Ciroma and the philosopher of “the new morality”

So, why shouldn’t the subalterns speak?

It is surprising that the NPN did a better job of conceptualising corruption than subsequent others. In the rulebook prepared for Shagari’s second term aborted by the December 1983 coup, the Shagari Presidential Transition Committee headed by the late Adamu Ciroma said, inter-alia: “The ‘new morality’ which has emerged from the military era is such that there is general acceptance among most members of the power elite that power is for profit rather than for responsible exercise of its privileges or for service …The ‘new morality’ encourages and protects chaos because members of the new elite have vested interest in chaos despite its long term danger to social stability and their real or permanent interests”. This is a classical example of a contextually sensitive framing of corruption. It is specific and critical.

The last practice of ‘silence’ to be pointed out is the exclusion of the universities. There are still many brilliant guys here and there in the Nigerian university system even as it is true that the universities are so down in terms of the Department of Sociology and Anthropology and Faculty of Law that can go beyond regurgitation of worn out definitions such as we are critiquing above. But, even when consulted at all, it is rarely beyond picking on one lecturer or the other most likely on the basis of some connection with the seat of government rather than in his or her capacity as an expert in his or her area of specialization. Without the experts of Nigeria’s cultural resources, our conception of corruption and how to undo it has been largely colorless, uninspiring and mechanical to move souls.

If all these were tolerable before the COVID-19 pandemic struck and showed that the self-acclaimed ‘giant of Africa’ is actually clay footed, they should no longer be. The destructive and unproductive nature of corruption in Nigeria makes them so. The country must put its foot down against the culture of the highest bidder winning everywhere, every time, using power, religion, region, money and sex to pervert examination grades, award of contracts, political appointments, elections and electoral jurisprudence, postings in government and what have we! Otherwise, the next pandemic would be messier. That is if we survive this intact.