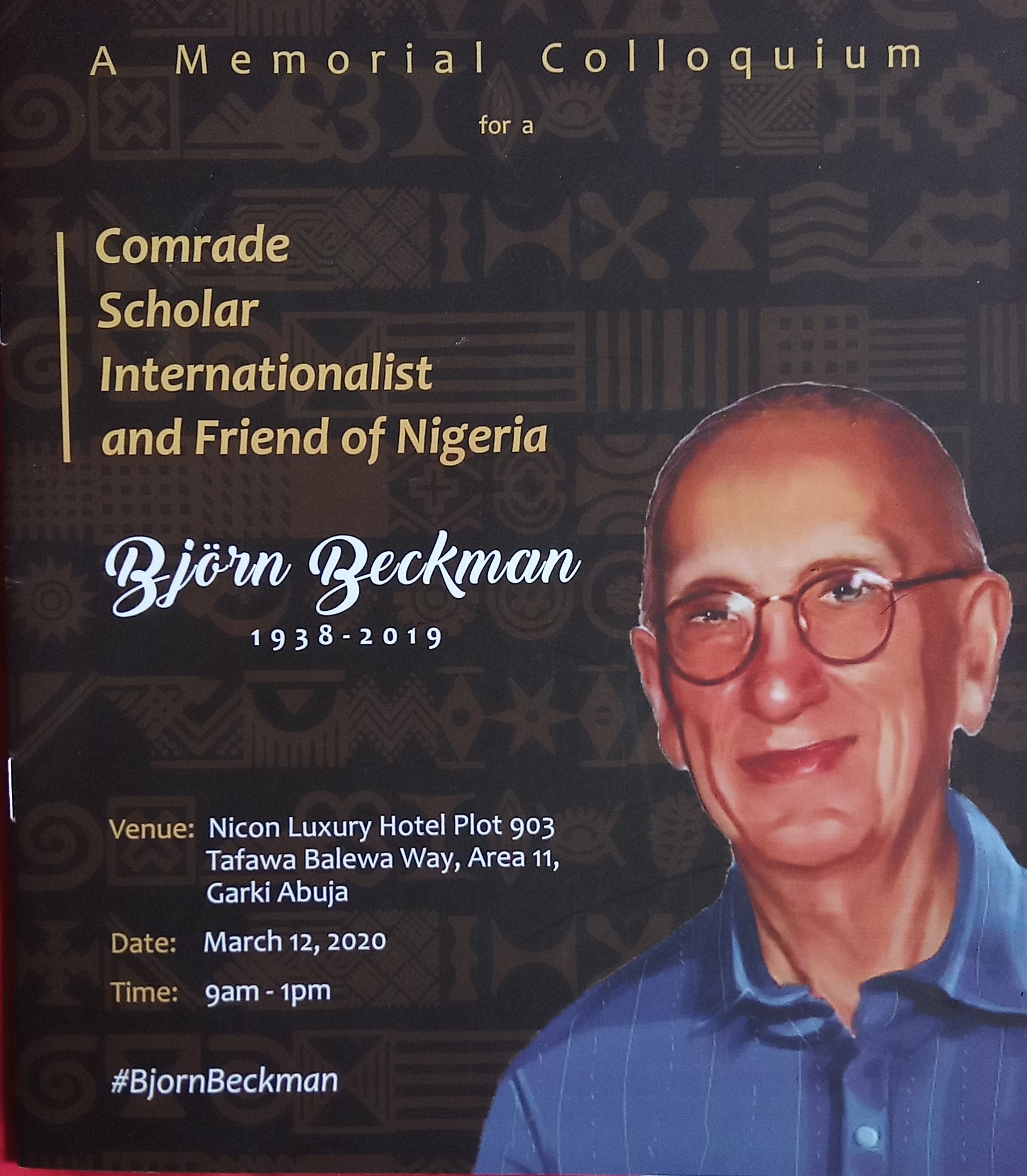

The open as well as muted case for break–up of Nigeria as an alternative to existing Nigeria has suffered a heavy blow from easily the largest gathering of radical activists in Nigeria in recent years. Not only was break-up of Nigeria rejected Thursday in Abuja, the radical activists also accepted the position of Prof Bayo Olukoshi, the lead speaker who argued that although the milestone of democratic transition in 1999 has failed to deliver on three most crucial variables, a time of painful experience such as Nigerians are going through is not the time for pessimism but of research for recovery.

The over four hour long event turned out to be one of many fascinating but critical re-engagement with history of radical academia as it unfolded at the Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria in the decade of the 1980s, especially as disclosed by Mallam Kabiru Abdullahi Yusuf, publisher of Daily Trust whose rare intervention touched on the problematic of petit- bourgeois radicalism, the trouble with objectivity as an article of faith in journalism as well as the potentials and limits of journalism itself in relation to the radical agenda and also by Prof A. D Yahya with his short but interesting admission of crisis and failure of the politics of ‘New Social Order’ the People’s Redemption Party, (PRP) attempted to create in the Second Republic from 1979 to the military coup in 1983.

Prof Yahya in an unclear picture taken from afar

Prof Yahya who wrote his name into the annals of Political Science scholarship in Nigeria with a PhD thesis in which the concept of ‘Kaduna Mafia’ received its most scholarly treatment before its bastardisation by the media was the Head of Department of Political Science when the late Prof Bjorn Beckman crossed over into Nigerian academia from Ghana where he first landed in West Africa.

According to Prof Yahya who replaced Dr. Bala Mohammed who was killed in the 1981 riot in Kano as the Political Adviser to the Abubakar Rimi administration, the ‘New Social Order’ politics which started from nothing to a success story in the two states of Kaduna and Kano lost its way into ordinariness because “we didn’t understand the tricks of politics”. The result, he said, was loss of its way into crisis, the subsequent loss of focus to the extent of the party becoming just another of the parties. In a way, he was confirming the reservations of the Zaria Group made up of critics of radical populism of the PRP as spearheaded by their colleagues in the PRP then under the now late Bala Usman. The tendency quarrel between the Zaria Group and the PRP intellectuals climaxed at the Marx and Africa Conference at ABU, Zaria in 1983. The December 1983 coup scattered everything and everyone involved in the explosive exchanges and since then, this is the first time a real insider has spoken.

Prof Yahya who corrected any impression of speaking in any official capacity in relation to ABU, Zaria praised Prof Beckman for taking them in a different direction in the aftermath of their interaction, a reference to Beckman’s variant of Marxian frame of reference in political analysis.

Speaker after speaker spoke in such an inspiring manner that it is difficult to decide the sequence to take the presentations and make the most of this attempt at synthesis. One way out might be to build all other standpoints around the lead speaker and leading African scholar, Prof Bayo Olukoshi’s presentation seeing as his spoke directly to the theme of Bjorn Beckman vis-à-vis “The Future of Democracy in Nigeria”.

Comparing the gathering to the African extended family way of mourning the head’s departure, Prof Olukoshi noted the difficulty of coming to terms with Bjorn’s death and being taken away at a time those he calls perpetrators of wickedness and worst abusers of the system were surviving. He, therefore, welcomed the opportunity to recover from that reality and take up the mantle of struggle with a robust sense of debate around trying to unravel forces and factors at play that he says were important to Bjorn’s political economy.

Starting with constructing a democratic profile of Bjorn, Olukoshi asserts how he had transcended democracy being something espoused outside while being a tyrant in the house. In other words, democracy was not an abstract thing but something oiled by a conversation around it and the associated practice regime, including what everyone is going to eat and who is going to cook it. Crucial to the spirit of conversation is the primacy of agency, the agency of peasants and workers in particular and Bjorn thus being a challenge to move democracy from the ritualistic to centralising the spaces of everyday in our engagement with the idea of democracy, away from the assumption that the people might not know what they want.

The last item in the profile is the fact that Bjorn did not ridicule the idea of rule of law, for example. Not for him the dismissal of such liberal canon as bourgeois instrument but something that is also part of the democratic checklist, a position that means that he was comfortable with African scholars such as Jibrin Ibrahim in his ideologically problematic castigation of his colleagues for making a career of wrongheaded bashing of liberalism.

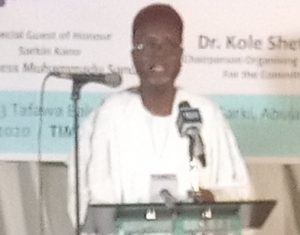

Prof Olukoshi making his presentation

Isolating Bjorn’s attack on promoters of military Vanguardism that was popular in Nigerian political analysis in the mid 1980s, Olukoshi argues that the late professor was right in warning against the phenomenon best exemplified by Jerry Rawlings in Ghana who was being called ‘Junior Jesus’. Bjorn’s ground is that it was a way of making way for disguised authoritarian elements, a position he is likely to take another look since retired Generals are the same elements who surfaced as democrats especially in the case of Nigeria since 1999. Where is the difference, critics are bound to ask. Would he have found a safe landing in the dismal performance of the ‘new democrats’?

Anyway, it was against this profile that Olukoshi offered Bjorn as the democratic referent which can be replicated through radical alliance politics for the rebuilding of Nigeria rather than the option of returning to some old regional structure or dismantling the country. He contested those saying it is time to face the reality that Nigeria won’t work or those interpreting Brexit to mean an instructive development as far as going separate ways is concerned, adding that such an option will confront multi-faceted roadblocks. Many, he said, would be unable to find their bearing or locate themselves in such a Nigeria.

The times, he said, calls for the sort of social science that Bjorn subscribed to because, according to him, “time of painful experience are not time for pessimism but of reflection and research for recovery”. It is also time to re-affirm faith in Nigeria rather than what he calls blind ways. Prof Olukoshi restated the case for building alliances across the Benue and the Niger as was done to dismantle military dictatorship and produce 1999 but now directed against the recklessness of the political class driving the country to devastating consequences.

He argues how central to Bjorn’s writing was the question of how people organise to invent a new future for themselves and that it is time to go beyond narrow confines at this time Nigeria has been over-run by radical extremism not reflective of religious dimension but of social dislocation.

He identified dislocation at three crucial points. One is at the level of nation building which is so bad today as signposted in the language of division. Two is at the level of state building. That is a functional state rather than a strong, authoritarian state. Instead of a functional state, 1999 to date has been a state of abdication or the state which has simply gone AWOL, abdicating its basic responsibilities. The third is what has now gone into Nigerian English as dividends of democracy.

The outcome of these three crucial failures is the gory stories of breakdown manifesting in criminality, gangsterism and excessive religiosity as people seek recovery in the spiritual space away from the temporal space. Life has become so cheap and Nigeria has become the hub of global poverty, he said, pointing at the tragedy in all these being how the national conversation is not one of rethinking the experience of the past 20 years but resorting to saying things such as 1914 being a mistake.

To this malady he reasserted his call for radical alliance politics, a position none of the three discussants of his presentation disagreed with although they added amendments.

Ngozi Iwere, a former Public Relations Officer of the defunct National Association of Nigerian Students, (NANS) and a community organiser endorsed radical alliance politics but drew attention to how unacceptable it is to sweep division in the country, ranges of inequality and crisis of social justice under the carpet. In other words, there should be a conversation. The question she is worried about is the question of who drives the conversation. Only democrats can build democracy, she says, a reference to the members of the collapsed alliances that fought military rule to 1999. However, her portrait for the members of the radical ancien regime is not a good one. She accuses them of junketing and fighting for money, concluding that “lack of internal democracy killed this movement”.

Dr Chermaine Pereira

Dr. Chermaine Peirera, the second discussant also endorsed the position but insisted on people looking beyond the spectacular character of recent spate of violence. She is sure that those who do would see how normalization of violence at the domestic space is implicated in the spectacular violence. In other words, we should be keen on whether labour’s struggles, for instance, stresses reproductive labour or what the Federal Capital Territory, (FCT) does on restriction of the space of women in the capital city. It is, for her, the violent discursive practices in those micro spaces that are the conditions of possibility for the spectacular violence we confront.

Professor Adele Junaid, the third discussant, started by calling Olukoshi’s an excellent presentation, revealing how he met and interacted with Prof Bjorn in Sweden in 1982. He found him interesting in the way Bjorn was approaching micro politics as a way of showing relationship at the macro level, He concluded on how this linked to “his strong solidarity with the human condition in the Third World”.

Continuing, Prof Junaid headed to what he sees as Bjorn’s relevance in current politics. In the light of Olukoshi’s call for radical alliance politics, he identified that in Bjorn’s caution against a polarised state – civil society problematic. For him, the question is what should be the role of the civil society and what have we learnt since 1999. Volunteering an answer, he says “what we have learnt is that anti-statist civil society has been co-opted, have become mirror images of what they fought/for”. Added to Iwere’s earlier charges, it was a bad day for the radical alliance which has already disintegrated. Still, what image of radical politics do these speakers, individually and collectively, post vis-à-vis Bjorn Beckman?

Olukoshi is stressing Bjorn’s respect for (popular) agency, suggesting that Bjorn was conscious that taking out agency in favour of instrumental reasoning and cold, unfeeling scientism were part of the problems of Socialism in Europe. Iwere’s position blasting the party mandarins if there had been a revolution in Nigeria is supported by an Adele Junaidu who has seen it all. Dr. Chermaine is arguing for autonomous space for gender in radical politics, the sort of position an environmentalist, an anti-war campaigner and nationalists would also have taken if they were on the panel. After all, as Archie Mafeje said in 1995, nationalism stabbed Socialism in the aftermath of First World War. He would have no need to edit it if he were alive to repeat it in 2020.

Even if the contour of radical politics suggested by the theoretical, ideological and organisational implications of these positions is what the memorial achieved, it has been a great day. Part 2 of this report will follow shortly!