By Ibrahim Lawal Ahmed

From January 21st-24th, the World Economic Forum (WEF) met in Davos, marking and celebrating the 50th Anniversary of the meeting. Over 3000 big shots in international affairs attended this year’s meeting. They included politicians from powerful countries of the world and business moguls from all the industrial and commercial sectors of the international political economy. These people always meet to discuss global political economy in order to explore ways to manage them collectively in collective interest or this is what they may appear to be doing. On the other hand, it has become a tradition for Oxfam, a non-governmental organisation founded in Oxford, United Kingdom with its headquarters in Nairobi, Kenya and committed to addressing global economic inequalities and alleviating poverty, to release its annual Report on global inequality.

Oxfam further interrogates the situation here

This year, as usual, Oxfam released its Report on the eve of WEF. Titled Time to Care, the report focused on the unpaid and underpaid care work and the global inequality crisis with emphasis on women. The report argues that economic inequality is out of control. In 2019, 2,153 people had more wealth than 4.6 billion people; that is half of the world population and 46% of the World or 3.4 billion people, live on less than $5.50 a day. These privileged few who own wealth equivalent to half of the world’s population are in fact less than the number of billionaires that spent and on whom millions of dollars was spent on this year’s WEF. The question is, why is the rich, rich and the poor, poor? This is a frequently asked question which is at the centre of all the Annual Oxfam Reports. I seek to answer this question in this piece by arguing it is property relationship that explains the situation of wide material and social gaps between the two.

The difference between prosperity and poverty is property. Properties are assets both tangible (such as houses, land and factories) and intangible such as shares and bond. While the rich own properties that continuously generate income to them, the poor depend upon paid labour by offering skills to the service of the rich. In other words, the poor depends upon being employed in the factories and industries built and owned by the rich. The property relation is such that ownership of property gives automatic ownership to commodities produced and the profit that accrue therefrom. Exploitation of wage labour is therefore a defining character of the socio-economic relationship. Directors of large corporations now earn two hundred times more than the lowest paid workers. Consequently, Sixty two (62) people as at 2015, sixty three (63) as at 2016, forty two (42) as at 2017 and twenty six (26) as at 2018 are worth half of the world wealth. This is a paradox; as the global wealth increases, the gap between the rich and the poor widens.

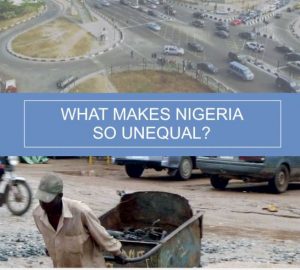

Economic inequality, even though a global phenomenon, is extreme in Nigeria. The gap between the rich and poor has continued to rise since the imposition of Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) in Nigeria, kick-starting the gradual privatisation of public enterprises, which is synonymous with transfer of ownership of public enterprises to private individuals, as well as fiscal austerity, trade openness and continues devaluation of Naira. The adamant and nonchalant attitude of our leaders about the issue is poignantly depicted as Nigeria ranks at the bottom for two consecutive periods (2016 and 2017) in terms of commitment to reducing inequality among all the countries across the globe. In a day, an upper class individual earns 8000 times more than the yearly consumption of an average Nigerian. Therefore, it is not something of a surprise that less than 20% of the population own half of country’s wealth and more than 80 million Nigerians are poverty stricken while the combine wealth of the top 5 richest individuals in the country is worth $29 billion whilst only $24 billion is needed to eradicate poverty in the country.

Chief Obasanjo insisted SAP must have human face but went for privatisation. Buhari insists the gap is too wide for comfort in Nigeria and found the answer in a higher VAT rate. Isn’t Nigeria then such a wonderful country?

When the State was most vulnerable and labour could have negotiated something substantial for workers, it went for N30, 000 ‘starvation wage’ which it is still battling to enforce as both the legislators who passed the bill and the governors play their own game

There are four factors that specifically drive this inequality in Nigeria. The first is Nigeria being a Rentier state. Taking the tax system in a Rentier State, for example, it is largely regressive as the burden of taxation falls mostly on small enterprises and poor individuals. On the other side, big corporation and multinational corporations, in particular, receive tax waivers and tax holidays, and utilise loop holes in tax laws to shift huge profits generated in the country to low tax jurisdiction. In the oil sector for example, section 19 of the Companies Income Tax Act (CITA) provides 3 to 5 years tax holiday, accelerated capital allowances after tax-free period in the form of 90% with 10% retention in books for plant and machinery, 15% investment capital allowance which shall not reduce the value of the asset, all dividends distributed during the tax holiday shall not be tax. Consequently, Oxfam reported that, every year, Nigeria losses $2.9 billion of potential revenues to tax incentives – tax holiday. Multinational corporations involved in LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas) had enjoyed tax holidays amounting to $3.9 billion. This is equal to about three times the total health budget in 2015. Senator Etok in 2015 disclosed that from 2010 to 2014, Nigeria had lost over N2 trillion to tax evasion. The former Minister of Finance, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, also disclosed that the Federal Government lost about N797. 8 billion to waivers and concessions in three years. That is from 2011 to 2013. All these huge amounts of money went to the pocket of few anonymous individuals; undermining the financial capacity of the government and by extension, the people.

Second is corruption and cost of governance. “Nigeria is fantastically corrupt” was the satiric words of former British Prime-Minister, David Cameron that is hard to dispute. Corruption has lost its meaning in Nigeria to the extent that former President Jonathan declared publicly that “…what are (sic) called corruption (cases) even by EFCC and other anti-corruption agencies, is not corruption but common stealing” The common stealing that His Excellency was talking about were the $20 billion allegedly unremitted NNPC account. Additionally, the cost of governance in Nigeria is sky high. It is such that Nigerian lawmakers receive annual salary of about N37 million ($118,000) before 2015. That is 63 times the country’s per capita as at 2013. It is pertinent to note that even though the law makers have claimed reduction in their salary and other allowances, there is no substantial evidence to back that. Moreover, governors made laws that granted them exorbitant salaries and allowances even after their tenure. These are what made some government officials super rich to the detriment of the masses.

Thirdly, the dependent capitalist nature of Nigerian economy perpetuates economic inequality. There is delink between production and consumption in Nigeria; we produce what we do not consume and consume what we do not produce. This makes Nigeria import dependent and vulnerable to inflation which sees to enrichment of the commercial bourgeoisie and dampening of the financial capacity of ordinary Nigerians. Moreover, production activities are mainly at the primary sector dominated by multinational corporations which are capital intensive. The capital intensive nature of investment in the most lucrative economic sector of Nigeria has resulted in skill-bias, granting employment to few skill workers. Education has since lost being a guarantor of employment with the mass shutting down of industries (8000 business were shut down between 2009 and 2011). And the economy is debt-stricken. Foreign debt runs the economy most especially from multi-lateral institutions, mainly the Brettonwoods. In 2020, N2.72 trillion is budgeted to servicing debt. What a capital flight?!

Last, but not the least of the specific drivers of inequality in Nigeria is the weak trade unionism. This can be seen in the recent struggle of the NLC and TUC to make government to adjust minimum wage to N30, 000. The more vigorous one, ASUU, suffers from public resentment due to their sole strategy of extracting compliance from the Federal Government – strikes. The trade unions focus mainly on public enterprises whilst there are many workers in the private enterprises. And they focus on the formal sector and skilled workers, neglecting the informal sector and the unskilled workers as well as peasants. In addition, they were unable to stop government from imposing policies and regressive taxes such as the recent increase in VAT. These weaknesses of Nigerian trade unions enable employers to determine and pay low wages and for the government to be nonchalant in paying pension thereby compounding poverty and all the more exacerbating inequality.

This background makes addressing inequality a political challenge. Barrack Obama is, in this context, correct to describe economic inequality as “a defining challenge of our time”.