If there is any region where France, as a global power, is being reminded that this is, indeed, the era of a decentered world, it must be in Africa, particularly West Africa. It is understood that the persistence and pervasiveness of anti-French sentiments are such that, apart from the Algerian contestation of it, France has probably never come up against that level of resistance of it on the continent. Used to primacy and privileges on the continent for, among other factors, its language cum cultural advantage in matters of gathering intelligence for other powers and for what is at stake for itself in the African pie, it is not clear whether France is getting the message and coming to terms with the inherent instability of hegemony.

Prof Jibrin Ibrahim in a previous picture

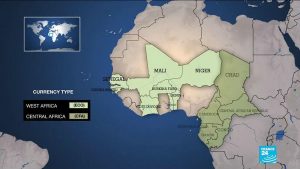

It is though instructive that French president, Emmanuel Macron is not averse to deploying defensive radicalism as in his calling colonialism a grave mistake last Sunday in Abidjan, complete with advocating for “turning the page”. But ‘turning the page’ does not appear to include strengthening the Eco, the ECOWAS region wide currency adopted earlier in the year. Rather, is includes the Eco being France’s punching point in what appears to be her response to being resisted in West Africa. But, what exactly could that be all about and how might it be located in terms of the dynamism of French exertions?

These were some of the questions Intervention took to Abuja based Nigerian political scientist, Prof Jibrin Ibrahim, for his insights. French educated, French speaking and deeply located in the diverse intersections of a French dominated region, Prof Ibrahim aka Jibo is the resource person’s resource person on the issue.

Professor Ibrahim began with a background of the French move to, sort of, strap the Eco to the Euro with all the implications of that, especially for a country such as Nigeria. His analysis is that a number of developments in the West Africa sub-region have alarmed France. One of these is the strong suspicion that France is the backbone of terrorism in the sub-region. There have been massive social media postings on this, showing that the West African public is convinced about this. There have also been open demonstrations on the streets of Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso on this. Professor Ibrahim is not quite convinced this is the case but he notes that what people perceive to be the truth is their truth, especially in this case where members of the Armed Forces also believe that France has a hand in terrorist strength in the area. He cites the argument about how Boko Haram insurgents could be moving in over 200 armoured vehicles to launch attacks without the surveillance system and high image producing drones will not sight them prior to the attacks.

The French, according to him, have put all these to Russian disinformation but it is angry with the Africans and have called a meeting to tell African leaders off. The meeting has been postponed for now but the French president plans to show his anger, to argue how he is sending his own soldiers to die in defence of Africans but yet be implicated in terrorist upswing in the area. Jibo’s contention is that while the public are against France, the leaders or the presidents in the Francophone countries are with France. In other words, what is playing out is the proverbial power of the people being mightier than the people in power. The presidents of Francophone countries as well as that of France are on one side while the people are on the other side in terms of whether France is a powerful promoter of terrorism in West Africa or not.

West African leaders who adopted Eco in June 2019

About the only other colleague the Nigerian president switched on a playful card.

The problem for France might be easier if this perception of it were the only snag. That is not the case from what Jibo is saying. There is what he calls a major campaign in the past five years within the Francophone countries to disband the French CFA. “That is a very strong campaign and it is spreading”, he says, adding how France has had to reduce its obvious financial control as a compromise. He then draws the grand conclusion that France realizes it is facing challenges to maintaining its control.

That is where he locates current French exertions on the Eco, the ECOWAS wide currency that has been in the pipeline since the 1980s. It has confronted difficulties in the Francophone countries being tied to the Bank of France and their own currencies being pegged to the Euro. However, the West African leaders never gave up until they achieved the adoption of a single currency for the sub-region last June.

That accomplishment now stands to be ruined from a single French move that will completely blunt whatever bite the Eco embodies. It is what the Francophone countries have done. They have adopted the Eco but accepted pegged it to the Euro. That is very clear from France 24, the French national broadcaster’s headline on December 22nd, 2019 viz “New Currency ‘eco’ to replace CFA franc but will remain pegged to euro”. By implication, it becomes the French currency without the exchange rate changing even though the Eco doesn’t have the strength of the CFA Franc/Euro.

For Jibo, the issue goes beyond that. It means the African countries using the Eco have simply lost control over monetary policy as a tool for development planning. It also means they do not need Central Banks any more since that is at the heart of central banking. Of greater implication is Jibo’s reference to a story on Radio France International, (RFI) on Monday morning, (December 23rd, 2019) in which the Finance Minister for the Republic of Benin was saying they have been in discussion with Ghana. “If that happens, it means Nigeria will be completely isolated”. By Nigeria in this sentence, Jibo means the English speaking West African countries that are being ‘convinced’ one after the other, a process which has started with Ghana as in the RFI story above.

Jibo is worried about Nigeria’s quiet in all these in the context of the formulation of the contest of power in Africa he credits to Professor Ibrahim Gambari. According to him, Gambari had said that Nigeria is an African power while France is a power in Africa. He, therefore, finds it surprising Nigeria doesn’t appear to have a position on what is unfolding. Meanwhile, Nigeria is battling with a different dimension of the problematic of France in the sub-region. The Republic of Benin and Nigeria’s contiguous nieghbour on its Southwest border cannot survive if it stops smuggling of rice, chicken and Turkey to Nigeria. Jibo’s narrative of the dynamics goes as follows: These products are imported into Benin Republic from China. They use certain chemicals on the chicken products in particular to ensure that they do not go bad. It is not that the central authority in Benin Republic smuggles them to Nigeria. It is that smugglers take care of that once the products arrive massively into Benin Republic. The amount smuggled into Nigeria of recent has reduced because of the border closure but it has not stopped. So, unlike Niger Republic, another of Nigeria’s contiguous borders which has ordered their smugglers off that line of business, Benin Republic is still a problem. It has studied what Nigeria lacks and it is keen to remain in that business.

Jibo is worried about Nigeria’s quiet in all these in the context of the formulation of the contest of power in Africa he credits to Professor Ibrahim Gambari. According to him, Gambari had said that Nigeria is an African power while France is a power in Africa. He, therefore, finds it surprising Nigeria doesn’t appear to have a position on what is unfolding. Meanwhile, Nigeria is battling with a different dimension of the problematic of France in the sub-region. The Republic of Benin and Nigeria’s contiguous nieghbour on its Southwest border cannot survive if it stops smuggling of rice, chicken and Turkey to Nigeria. Jibo’s narrative of the dynamics goes as follows: These products are imported into Benin Republic from China. They use certain chemicals on the chicken products in particular to ensure that they do not go bad. It is not that the central authority in Benin Republic smuggles them to Nigeria. It is that smugglers take care of that once the products arrive massively into Benin Republic. The amount smuggled into Nigeria of recent has reduced because of the border closure but it has not stopped. So, unlike Niger Republic, another of Nigeria’s contiguous borders which has ordered their smugglers off that line of business, Benin Republic is still a problem. It has studied what Nigeria lacks and it is keen to remain in that business.

From this narrative, Jibo concludes that Nigeria’s interests are at stake in all the three main dimensions of the problematic of France in West Africa. One is the public suspicion of France as the power masterminding terrorism in the sub-region. The second is France’s move to blunt the bite of the Eco while the third is certain behaviour pattern of contiguous nieghbours strongly linked to France.

These are the reasons why he is intrigued by Nigeria’s silence on France’s exertions. Is it a case of what the Nigerian government knows and the question of how much room for manoeuver it has in relation to France in West Africa or a case of a government that is not clear of what is at stake? Perhaps, only time will tell! Unless it is an informed/strategic silence, the government would have to speak. If the degree of African sensibility on the Eco issue so far is anything to go by, then this is where the African power, ala Gambari, must manifest itself.