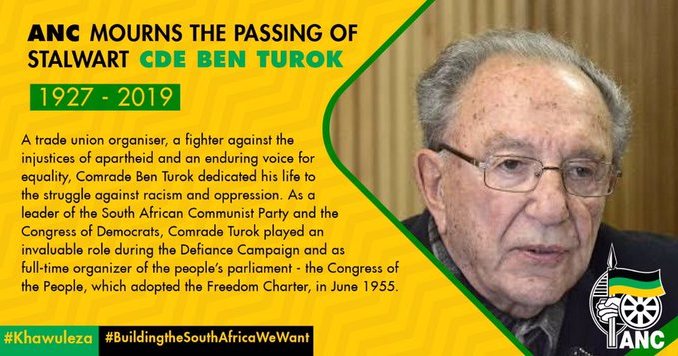

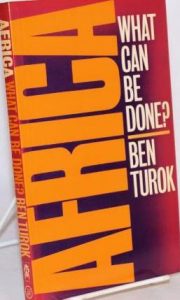

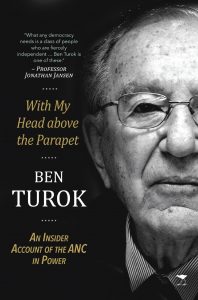

Africa is mourning again and at the same time contemplating the future along Professor Ben Turok’s all time significant poser he raised more than 30 years ago in a book form: Africa: What Can Be Done? Many would say that the most significant aspect of the the formidable voice for emancipation and anti-Apartheid activist who passed away earlier today is summed up in that poser, with particular reference to what should happen to Africa in the current unraveling of the world order into which the continent was born in a manner that denied it any say.

Global capitalism emerged in the 19th century with few centres of powers by which everything else was measured – culture, religion, politics and economic models. This happened at a time the entire African continent was being systematically ravaged and constructed into an appendage of its Others.

Global capitalism emerged in the 19th century with few centres of powers by which everything else was measured – culture, religion, politics and economic models. This happened at a time the entire African continent was being systematically ravaged and constructed into an appendage of its Others.

However, for the first time in human history, there is what Fareed Zakaria calls “the rise of the rest” into the table of global power. This is a completely new struggle for which no old narratives or dogma is adequate in terms of Africa’s ascendancy, given the complexity, inter-penetration and simultaneity in contemporary world dynamics. It is a battle of framing which Africa has yet to register.

Turok’s question of “what can be done? is argued to be drawing Africa’s attention to this question of how Africa may write itself into the table of global power in the aftermath of the on-going reconfiguration of that architecture. This re-interpretation of Turok’s book does not annul the ideological critique he put on the table when it was first published.

In any case, his poser is the subject of a debate which is already, both by those who are aware as well as those who are not aware of the question as he posed it.

There are those in favour of the politics of the ‘multitude’ expressed in the anti-globalisation movement/World Social Forum politics, notwithstanding its limitations as well as the potentials. It is undergoing re-working, with particular reference to how it can achieve decentering existing world order. For proponents of politics of decentering the existing world order, everything else – justice, equality, emancipation, etc will be added unto the world if the next world order has no centres of power by which Others are measured. That is what they see as the key contradiction because of the way global capitalism has so successfully used the media and culture to sustaining hegemony. This stance explains the excitement when the idea of the G-2, (the Great 2 – China and the USA) failed to fly because it would have meant the return of centres and peripheries.

There are those in favour of the politics of the ‘multitude’ expressed in the anti-globalisation movement/World Social Forum politics, notwithstanding its limitations as well as the potentials. It is undergoing re-working, with particular reference to how it can achieve decentering existing world order. For proponents of politics of decentering the existing world order, everything else – justice, equality, emancipation, etc will be added unto the world if the next world order has no centres of power by which Others are measured. That is what they see as the key contradiction because of the way global capitalism has so successfully used the media and culture to sustaining hegemony. This stance explains the excitement when the idea of the G-2, (the Great 2 – China and the USA) failed to fly because it would have meant the return of centres and peripheries.

This question remains unsettled even as the unraveling of the existing world order is proceeding apace with so much confusion at all the existing centres. The Samuel Huntington framework of clashing civilisations is not quite working as there are both clashes of civilisation as well as convergence of civilisations. The alternative idea of a return to a revised “Concert of Europe” especially the variant coming from people like Leslie Gelb, the author of Power Rules. The G-2 idea too has also failed to fly. It is in this context that Ben Turok’s poser has a new meaning with his passage. After all, texts do not have static meaning.

His own personal attempt at building a coalition against the Apartheid regime in its twilight as well as transforming into a politician are re-interpreted to mean important shifts in popular struggle for hegemony. How far the experiment of social transformation through ‘democratic’ politics has gone in South Africa will be used to critique what he did, especially by those who still believe in Jacobinism as the way to power in spite of the contradictions and logistic nightmare of that strategy under digital capitalism. Embodied in Ben Turok at death are questions of the extent to which each and every of such a strategy is an option.

His own personal attempt at building a coalition against the Apartheid regime in its twilight as well as transforming into a politician are re-interpreted to mean important shifts in popular struggle for hegemony. How far the experiment of social transformation through ‘democratic’ politics has gone in South Africa will be used to critique what he did, especially by those who still believe in Jacobinism as the way to power in spite of the contradictions and logistic nightmare of that strategy under digital capitalism. Embodied in Ben Turok at death are questions of the extent to which each and every of such a strategy is an option.

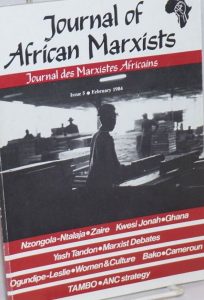

Beyond supplying a big poser for continuing reflection and his practical politics example, he will be remembered for his strong intellectual cum agency presence. He worked tirelessly for a journal that did not survive but which elevated Marxian theory and practice beyond regurgitation within the short time it was published. That is the Journal of African Marxists. It provided an important space for the Marxist imagination from the African specificity. It was thus a success story in innovative deployment of popular culture, bringing Marxist geopolitics into radical politics. He is understood to have worked a lot with Professor Bade Onimode and Tajudden Abdulraheem on the journal. How great it would have been if the journal has survived that team and even greater if it could be revived to serve as a space for more creative Marxism that speaks to Africa’s spaces of everyday.

A man of multiple abilities – publicist, organiser, academic, combatant and politician, it would be difficult to exhaust his story at a go.