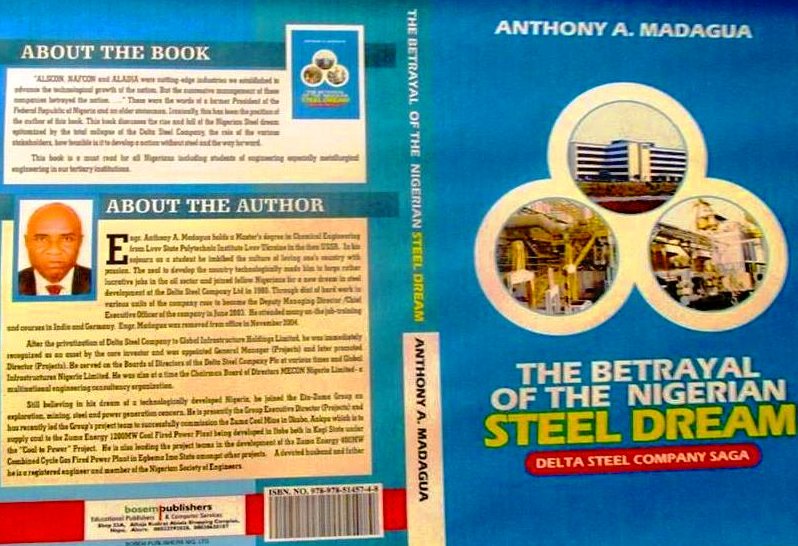

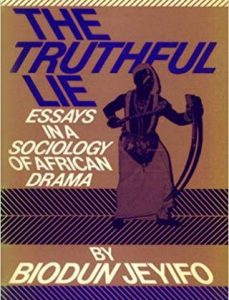

At a time of sensational articulation of private enterprise as Nigeria’s way out of woes, it is important that an intervention such as this talk below is further circulated beyond an elite newspaper. This is because, ordinarily, the subject matter of this talk ought to be the dominant if not the only item on the agenda of the current electioneering campaign. Unfortunately, it is not. That it isn’t is, for those who know, the most threatening indicator of the enormity of the crisis in Nigeria. Prof Biodun Jeyifo, Harvard Prof of African Literature and the author of the piece called it “The Business of Business and the Business of the Nation”. Intervention has re-titled it “Prof Biodun Jeyifo on the Dangers of De-Statisation. There is no attempt to summarise it so that readers can make their own sense of it. Originally remarks at the University of Ibadan School of Business on Friday, January 18th, 2019, it was published in The Nation, January 20th, 2019 where Jeyifo runs a weekly column.

Prof Jeyifo, a former National President of ASUU years ago brings back the debate on business model in Nigeria

Prof Biodun Jeyifo on the Dangers of De-Statisation

Prof Biodun Jeyifo on the Dangers of De-Statisation

About a month ago, the ruling APC rather abruptly withdrew the name of the richest man in Nigeria and Africa, Aliko Dangote, from membership of the campaign organization for the reelection of President Muhammadu Buhari. In making the retraction, the Buhari reelection committee took care to let the public know that Dangote had not been consulted before he was named a member of the committee. And indeed, most Nigerians had been astonished to hear that Dangote was going to be campaigning for Buhari – or indeed for any politician or political party. For, doesn’t everybody know that super-rich business moguls like Dangote are too big to be used by any government, any political party, any politician for their partisan political interests?

In the same vein, consider the case of the American multi-billionaire, Bill Gates, one of the richest men on the planet. Slightly over a year ago, at an address that he delivered to the Nigerian Economic Council (NEC), Gates asserted that the Nigerian economy is so badly managed that needless poverty is rampant and pervasive in the country and ours is one of the worst places in the world in which to be born. Those gathered at the event where Gates made this shocking remark included some of the biggest names in the “Who’s Who” list of Nigerian politics and economy. In other words, all those present to listen to Bill Gates’ scathing rebuke of the management of affairs in Nigeria were men and women who are not used to being told, publicly, that their country, their homeland, is one of the worst places on the planet in which to be born and in which also to die.

What is the common element in these two separate accounts about our own Aliko Dangote and the American, Bill Gates? It is this: they are both so rich, so independent of government patronage that they cannot be pressed into service in support of the partisan politics of politicians, including even the most powerful among them, like President Buhari. It is of course possible that Dangote is both a supporter and an admirer of Muhammadu Buhari, just as most people in America know that Bill Gates is ideologically and politically much closer to the Democrats than the Republicans. But this is absolutely without prejudice to the fact that both Dangote and Gates do not need the patronage of government, of politicians to sustain and expand the vastness of their personal wealth and their corporate financial power.

Bill Gates and Aliko Dangote, his Nigerian counterpart with President Buhari whose economic framework he, (Gates) critiqued during the visit at a speech right in the Villa

Can we think of any other businessman in Nigeria apart from Aliko Dangote who is so wealthy, so successful in doing business in many countries in Africa and beyond that no presidents, governments and ruling parties of our continent can get him to campaign for them? The answer is no. Well, perhaps one or two others beside Dangote. I can think only of Michael Adenuga, but I am not as sure of him as I am of Dangote. Now, compare this to the situation in the advanced capitalist countries of the world in Europe and North America where typically, most, or indeed all of the business magnates are not only independent of the patronage of politicians but are actually the patrons, the “godfathers” of presidents, prime ministers and ministerial cabinet members. This in effect means that while Dangote is an exception in Nigeria, Bill Gates is the norm in America. In other words, while in America and the other advanced capitalist nations of the world, business has seemingly broken free of dependence on the government or the state, in Nigeria and many other countries of the developing world, business is (still) shackled to the state – with the lone exception of an Aliko Dangote. There is a slogan that goes to the heart of this historic phenomenon and it is this: business is not the business of the state; it is the business of business. This slogan, this truism about the relationship between business and politics in advanced postindustrial capitalism is what I wish to explore in my talk this afternoon.

Can we think of any other businessman in Nigeria apart from Aliko Dangote who is so wealthy, so successful in doing business in many countries in Africa and beyond that no presidents, governments and ruling parties of our continent can get him to campaign for them? The answer is no. Well, perhaps one or two others beside Dangote. I can think only of Michael Adenuga, but I am not as sure of him as I am of Dangote. Now, compare this to the situation in the advanced capitalist countries of the world in Europe and North America where typically, most, or indeed all of the business magnates are not only independent of the patronage of politicians but are actually the patrons, the “godfathers” of presidents, prime ministers and ministerial cabinet members. This in effect means that while Dangote is an exception in Nigeria, Bill Gates is the norm in America. In other words, while in America and the other advanced capitalist nations of the world, business has seemingly broken free of dependence on the government or the state, in Nigeria and many other countries of the developing world, business is (still) shackled to the state – with the lone exception of an Aliko Dangote. There is a slogan that goes to the heart of this historic phenomenon and it is this: business is not the business of the state; it is the business of business. This slogan, this truism about the relationship between business and politics in advanced postindustrial capitalism is what I wish to explore in my talk this afternoon.

Permit me to repeat this idea that I am exploring with you this afternoon: business is not the business of governments; it is the business of business itself. As a widely and pervasively practiced phenomenon, this idea is valid only in the advanced capitalist nations and economies of the world; in a developing country like ours, it is not valid at all. This is because business, especially big business, is still in Nigeria heavily dependent on contracts, franchises, leaseholds and charters obtained from the government. Indeed, most of our big businesses would collapse if they lost touch or favor with their contacts within the governments of the country, especially at the federal and state levels. But all the same, the idea is now widely held and believed in our country that government should have very little or no say at all in the running of businesses. Perhaps the most radical, the most uncompromising expression of this idea is the contention that governments do or run business so badly and poorly that they should have no hand at all in doing or running business.

At this point in my talk, it is perhaps useful to identify two distinct but closely linked ideas and beliefs in the contention that business is the business of business and not the business of governments. First, there is the idea that governments should not own or run businesses at all since, so it is argued, they tend to loot the businesses they run and/or operate them extremely incompetently. The second idea is the belief that government should keep the regulation of businesses as little as possible, some militant purveyors of this idea going as far as to argue and fight for complete deregulation of businesses by government. Please, note that these two ideas are separate and distinct: one pertains to the ownership and operation of businesses by government; the other pertains to governmental regulation of businesses and business practices. But usually, both ideas are joined together in the expression that I am exploring with you in this talk – business is not the business of government; it is the business of business itself!

The University of Ibadan School of Business but what view of business?

Chief Mike Adenuga, the second of the success stories in private enterprise in Nigeria

It should have been obvious that the fact that I am giving this talk to a Business School greatly influenced my choice of this topic for my talk. I mean, what sense would this topic have made if I was giving this talk to students of drama and theatre at this university? Yes, it would have been of some interest to them, but that would have been nothing close to the interest it ought to generate among you, the specific audience for and to whom the topic is targeted. As a matter of fact, I have a sneaking suspicion that most of you believe and accept the contention that business is not the business of government, it is the business of business. Indeed, I will put this hunch of mine to the test and now ask you directly to indicate by a show of hands whether or not you believe in this contention. Extending this playful test further, let me now ask which of the two ideas within the contention you accept more fully and unreservedly, the idea of government ownership and operation of businesses and corporations; regulation of businesses and business practices by government.

It should interest you to learn that on these questions, the great business schools and newsmagazines of the world are divided. For instance, take the Harvard Business School (HBS) and the London School of Economics (LSE). HBS is solidly on the side of maximum to near complete privatization of publicly owned businesses, while historically, LSE has been a solid defender of the mixed economy model in which certain critical sectors of the economy are deemed so crucial to the social good, to the survival of the entire national community, that they must never be wholly privatized. This same division is apparent between two of the foremost newsmagazines on economics and business in the English-speaking world, the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) and The Economist. Like the HBS, the Wall Street Journal believes and argues strenuously for divestment of governments from business ownership and as little regulation as may be (regrettably) necessary. By contrast, while The Economist is for free trade, it is ideologically a powerful advocate of economic liberalism and is generally against massive deregulation and extensive to complete restriction of governments from owing and running businesses and corporations in the public interest and for social good.

At the University of Ibadan Business School, what do your lecturers and professors teach you about these critical, historic issues? I may be wrong, but I suspect that they do not talk about these issues at all, or perhaps only fleetingly, when a course or a project pertains to their consequences at specific moments of economic history. Well, I hasten to tell you that we are at such a moment of national and global economic history, the time and the world of neoliberalism and the crises it has precipitated in virtually all the regions and nations of the planet. This is because neoliberalism has combined and subjected to withering attack the two distinct ideas in the subject of our talk – public or governmental ownership of businesses; and governmental regulation of businesses and business practices – in a manner that no previous period of economic history has ever managed to achieve. This observation leads me to the heart of my talk this afternoon: What should the University of Ibadan Business School, what should all the business schools and economic departments in our country be teaching it/their students about neoliberalism?

Harvard Business Review and its globalisation imaginary

Another tireless promoter of the logic of neoliberal globalisation

Please, note that I said “should” and not “ought”. In other words, I am not presuming to dictate to our business schools and economics departments what they ought to be teaching their students about neoliberalism. What I am saying, what I am strongly suggesting, is that they should talk extensively and openly about neoliberalism, with special emphasis on the Nigerian experience of this global phenomenon. This is partly because since it affects everybody, every soul on our planet, people all over the whole world are talking intelligently about neoliberalism. But more to the point, it is because Nigeria is one of the few places in the world where it is widely believed that neoliberalism has won a decisive victory against its liberal and leftist opponents. In concrete terms, there are few countries in the world where, like present-day Nigeria, most politicians, most public officeholders, most policy makers believe that government should stay out of business, should privatize and sell all public-owned enterprises and assets, and should keep governmental regulation of businesses to the absolute minimum necessary.

At this point in my talk, some concrete details are helpful to give flesh to the bare bones of these observations and claims of mine. Thus, just take a look at the list of the number of public enterprises and national assets that have been wholly privatized. The building of roads, highways, bridges and other public utilities have been massively privatized, so much so that only Nigerians older than fifty know of a time when all these aspects of our physical infrastructures were all built by a division of the government known as the PWD, the Public Works Department. Essential social services like waste disposal and public sanitation have been massively privatized where, once upon a time and back in the day, they were operated by designated arms of the civil services of the federal, state and local governments. Education, at all levels, has been massively privatized, with much greater negative impact at the tertiary level. Even the collection of taxes and tollgate fees has been privatized in many states and localities of the country. As I write and deliver this lecture, there is much talk and agitation to completely privatize the energy and oil sectors of our national economy. Indeed, the privatization vultures have their eyes and gullets particularly focused on acquisition of the national oil corporation, the NNPC. Your guess is as good as mine on how long the resistance to this ultimate dream of total privatization in our country will hold.

Are public enterprises and social services owned and operated by the state uniformly inefficient and corrupt in all cases and around the whole world? That is not the case! And in Nigeria, what has been the experience of the privatization of state-run enterprises and public utilities? Have not the goods and services delivered by privatized state enterprises been as poor and sub-standard as when they were run by parastatals and public officeholders? If we have, at one time in this country, known and experienced public enterprises and utilities that worked efficiently, what went wrong in the political economy of the nation to make the very thought of having government-owned businesses and public utilities unwelcome and unwholesome to most Nigerians today? And, finally, are not the businesses run by business as bad and as inferior as businesses run by government, the state? Are corruption, mismanagement, looting and conspicuous consumption not equally and massively present in the business of business and the business of the nation?