By Adagbo ONOJA*

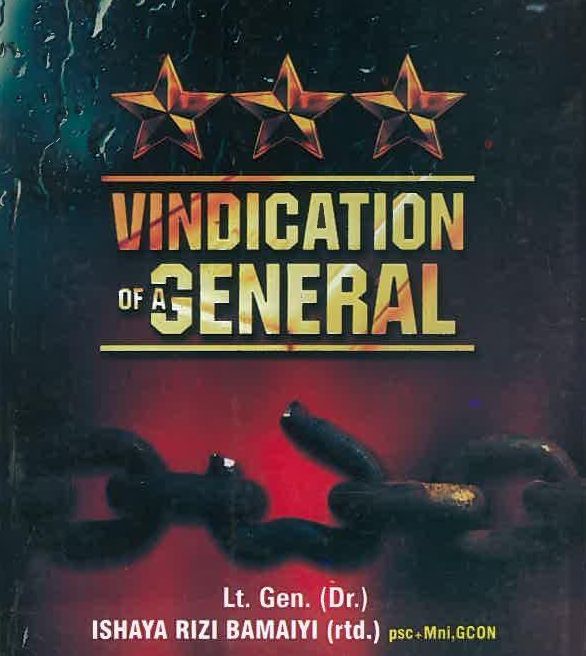

One of the classics of junta politics

It is a classic opening of the proverbial can of worms, with particular reference to that phase of the Nigerian power politics which unravelled from December 1983 to 1999 and which General Ishaya Bamaiyi has chronicled in this book. As such, Vindication of a General is an evocative read in struggle for power along a diffuse pattern of loyalties within the Nigerian military in the period in question. Being a struggle for power underpinned by no clear ideological tendencies, the free play of dirty tricks by which it was operationalised provides an entertaining but disturbing details about our recent past. More so that these details have come in a full length book by someone who was a referent actor in the entire drama, coming out with such a rich repertoire of the series of confrontation between contending constellations of power lost in a medley of dirty tricks. So, it is a story of politics within the military under the condition of the military in politics, a condition in which the army, nay the armed forces, Nigeria’s most strategic national security formation, transformed itself into a threat to national security via false security reports against each other, subterfuge, skulduggery, conspiracy and counter-conspiracy, disinformation as well as mystery accidents. It is, in that sense, an African story too, resonating with the late Professor Claude Ake’s consideration of military rule as the most imponderable reality. He had in mind the sense of danger that defines the military profession such that the typical military man is simply ill at ease in the arena of democratic politics. Instead of seeing competitors to be won over, he or she sees enemies and conspirators out there to be conquered in a do or die test of strength.

The most striking paradox that sticks out in this book is the repudiation of a fascinating becoming: the rise of the son of a pastor from the old Sokoto Province in the now defunct Northern region to the position of the Chief of Army Staff, (COAS) of Africa’s erstwhile most powerful military but only for him to end up in the prison cage for eight years. What happened? How might that be understood? Bamaiyi provides a leading argument in his book which the title embodies. It is a celebratory account of what he considers to be a vindication of his standpoint in the post Abacha transition that nobody with a military background should be allowed to take over power from the military regime in 1999 as the president of Nigeria. Not only did he push this position vigorously, he equally indicated a preference for Chief Olu Falae, going to the extent of introducing him to General Abdulsalami Abubakar in the context of the consensus that the next civilian president must come from the South West so as to annul the annulment of MKO Abiola’s victory in the June 12th Presidential election in Nigeria in 1993. That, he said, posed him against the triumvirate of IBB, T. Y. Danjuma and Aliyu Gusau whom he contends had convinced General Abdulsalami Abubakar on General Obasanjo’s candidature. The metamorphosis of Obasanjo’s candidature into the Obasanjo Presidency in May 1999 made him ‘dangerous’ and a specie to be kept out of circulation “for the health of democracy”. Added to the existence of a well knit oppositional group against his person and position in the military as well as an all consuming family feud between him and Major-General Musa Bamaiyi, his senior brother, a battle that must have robbed him of family impregnability that he otherwise had, Bamaiyi tells the story of a design that was easily accomplished.

But a vindication came for him. The vindication in this book, for the author, is that moment when General Babangida whom he credits with constructing the Obasanjo Presidency admitted in Daily Sun (August 17th, 2011) that Obasanjo had been a failure, had ran a regime that was bereft of foresight and imagination, thereby wasting Nigeria’s resources. Subsequently, Bamaiyi declares, “I stand vindicated for opposing these generals who supported my arrest and detention for opposing Obasanjo as the president of Nigeria in 1999. I paid the price for my stand but Nigeria is paying a higher price for Obasanjo’s wickedness to Nigeria, especially the northern part of the country. The generals now know better, and I believe they know they cannot play God. Sometimes when you think you are the wisest person, you turn out to be the greatest fool”.

Gen Bamaiyi

The late Gen Sani Abacha, Bamaiyi’s source of power in the context of junta power play

Every other detail in this book stands in relation to this ultimate feeling of vindication, combustible in its combination of sadness and joy, powerlessness and powerfulness, castigation and celebration, the jeer and the cheer, both for the self and for the country. It is the contradictory stuff of such moments in History. The drama that fills this long story compels us to go beyond this main gist of the book, by undertaking a sweeping tour of the work. Only by so doing might we more deeply reflect on the implications of the narrative. Thankfully, Bamaiyi’s key argument is narrated in a complex of sub-scripts, each leading to the next until the climax when he was arrested shortly after the transition programme in 1999 and was never to be free again till 2008. That chronological presentation not only makes it easy to follow but also helps in holding together the various dimensions as a wholesome story across a critical stretch of time in the country’s history.

Beginning from the beginning, Bamaiyi’s account opens with a Prelude in which the difficulty which confronts most peasant families in agrarian Africa in the education of their children played out. In this case, the children were many – 12 of them, eight boys and four girls. As was and still is the practice, the girl child drops out in favour of the males. Beautifully though, almost all the children in this case acquired education, what with a self-help minded Ishaya Bamaiyi who could, quite early, walk up to one of the school heads to argue why he couldn’t work on the Mission compound after school and on weekends for a pay? That way, he could pay his own fees and his parents could then bother about two of his other brothers. It worked. All roads eventually led to Bida Teachers’ College in 1962 where Musa Bamaiyi, his senior brother, joined him in 1963 and from where they all graduated into the Nigerian Civil War in 1967. Ishaya had been stopped from joining the army by a relation before he saw an advertisement for Grade Two teachers to be recruited as education instructors. He applied and was taken, again dragging along his brother Musa who was not initially involved in it.

A few months of involvement in the war and he went on what qualified to be called Away Without Official Leave or (AWOL) in military language but only to get into the army properly by responding to another advertisement for the Nigerian Defence Academy, (NDA) emergency commission. In 1968, he ended up on posting to 2 Division of the Nigerian Army at Onitsha as a 2/Lt, no more as a Non-Commissioned Officer. Chapter Two is a tale of life threatening experiences that served as an interregnum between the end of the war and the maturing of an officer. Thereafter, a new phase opened, the first major drama of which was the Orkar coup of April 1990 when the author was already the Commander of the Lagos Garrison Command. The highlight here is the intelligence failure that defined the Orkar Coup. Neither the SSS nor the intelligence units of the various armed services detected the coup even as open as the preparations were in the author’s view. Bamaiyi wonders why no one was punished.

The narrative here privileged how he was roused from sleep by a special security bell that had never been used, signalling trouble. He narrates a story of confronting risks, being shouted at by gun wielding Non-Commissioned Officers who had taken over the Cantonment and were firing, mostly blindly, making several officers to demonstrate cowardice in the face of fire instead of demonstrating courage. But he gives a list of majors that he credits with saving the day while putting down General Aliyu Gusau, his General Officer Commanding, (GOC) 1 Mechanized Division for being nowhere to give directives even though he was in Lagos. He recalls a telephone from General Abacha by 3 a.m that night of fire who wanted to know what was going on. After telling Abacha that the Cantonment was safe although there had been incredible firing, he was handed over to IBB to whom he paid the military compliments.

Gen Obasanjo, a permanent referent in Nigeria’s junta politics

The drama moves to the 1995 Coup involving Generals Obasanjo, Shehu Yar’Adua, Lawan Gwadebe, Bello Fadile, among others. The author’s verdict is that there was, indeed, a coup plot and that there is nothing phantom about it.That is why General Mujakpero and Patrick Aziza, the officers who investigated the coup and carried out the trial respectively have stood their grounds about the appropriateness of what they did. In putting the genealogy of the coup on display, Bamaiyi asserts how Alwali Kazir, the GOC of 1 Division in 1995 confirmed to him rumours of the plot when he asked him about it but did nothing about it for some time. It was later that Kazir, after becoming the COAS, called a meeting at which the decision to eventually arrest the planners was taken. This is to suggest a painstaking investigation that took some time.

Bamaiyi contends that there is a tape which would have convinced Nigerians that Obasanjo plotted the coup but that when the tape in question was to be played at Oputa Panel, “Obasanjo used his position as president to cover up his involvement in the 1995 Coup”, (P. 14). So, he argues that he and Aziza went to plead with Abacha for Obasanjo to be pardoned and released not because they were not convinced of Obasanjo’s involvement but because Obasanjo and Yar’Adua was a former Head of State and a deputy respectively. The paradox, he argues, lies in Abacha being the only military Head of State who spared convicted coup plotters, leading to people calling the attempt a phantom coup. He is, therefore, hoping that the day would come when the tape recording in question would be played for Nigerians to listen. Meanwhile, he raises the poser: why did Obasanjo pardon the officers convicted with him but didn’t do the same for the set of convicted coup plotters in 1997?

1997 Coup has the same storyline as that of 1995. Bamaiyi’s account is that Oladipo Diya, the Chief of General Staff in the Abacha administration started grumbling against Abacha quite early in the life of the regime, alleging that Abacha was neither coming to the office early nor listening to anyone. As the Commander of Lagos Garrison Command, Bamaiyi received the CGS each time he visited Lagos. From the account in this book, it seemed that each time he did, Diya added value, declaring flatly at one point that Abacha had to be removed, a process he thought Bamaiyi would be crucial. When General Patrick Azazi took over Lagos Garrison Command after Bamaiyi became COAS, Diya repeated the same stuff to him who, alarming him enough to go and see his COAS. The two went to Abacha, imploring him to call Diya to be confronted with the evidence and then be retired. Abacha declined, preferring to put Diya on trial based on how much more information they gathered. Thereafter, Bamaiyi and Aziza joined Diya in “plotting” to overthrow Abacha without Diya suspecting they were briefing Abacha.

Of course, they were rounded up on the day of the coup, according to this account but it was to inaugurate, for Bamaiyi, a completely contradictory kind of trouble. The Defence as well as the Military Intelligence had not uncovered the plot on their own. And since Abacha had directed they should be kept out of the progression of the plot, they ended up with an intelligence failure on their hands, a professional and political disaster for them. To this, Bamaiyi trace his trouble: “they started doing everything possible to ensure that Aziza and I were charged for the coup, knowing very well I was reporting to my superior officer”, (p. 24). Although Abacha rebuffed their pressure, the author tells us he went to Abacha to seek permission to appear before the Chris Abutu Garba led special investigation. Neither Diya nor Adisa had any questions for him when he appeared. Those who also thought that their appearance meant they could not return to their positions were disappointed too. But, Peter Nwaoduah, the DG of the State Security Service (SSS) at the time testified that Bamaiyi plotted the coup, the tape of which testimony Bamaiyi claims in the book to have obtained.

Gen Babangida and Gen Abacha, two other key actors in Nigeria’s junta politics

Bamiyi challenges General Chris Alli, his predecessor in office who had claimed in another book that Diya was set up after having written in the said book that Diya had suggested the overthrow of Abacha thrice. He, therefore, wonders why anyone would buy the claim that the coup was a set up to get those who were opposed to Abacha’s self- succession plan. In dismissing this, the author makes the point that as Commander in Chief, Abacha had the power to retire any of his subordinates at any time as happened to Chris Alli when he was found plotting a coup.

In taking Diya up subsequently, Bamaiyi isolated a particular interview in Tell where Diya claimed that Bamaiyi, Chris Alli, Abdullahi Ahmed and Bashir Magashi had tried to set him up earlier in 1996 by proposing the arrest and assassination of IBB, but that he declined permitting them because it was a set up, a plan to implicate him. Bamaiyi’s question is: if Bamaiyi had participated in trying to set Diya up in 1996, why would Diya agree to deal with the same Bamaiyi again in 1997? And how could the CGS afford to keep quiet about a suggestion by any set of persons to arrest and assassinate Babangida?

The offensive from the intelligence continued but Abacha’s defence of Bamaiyi as the most loyal operator remained solid. Although it never abated, it was like as long as Abacha was in charge, Bamaiyi was safe. He had appointed him in March 1996 as COAS, calling him directly to ask him to watch NTA News that evening. The news in question turned out to be the announcement of his appointment as COAS. And the intelligence operators had not been able to remove him since then even though they had boasted they were adept in removing people from positions for which the appointee was not their own making. He recalls the filling of the 1996 COAS Training Conference in Sokoto with intelligence operatives who reported and read meaning into everything, including how people laughed. And went on to cite how Dangiwa Umar as well as Aliyu Gusau became victims of such misuse of intelligence, involving, in the case of Umar, a scenario in which one man was being invested with the capability to single handedly plot and effect a coup.

His situation was not helped by among others, his decision to embark on a tour of army formations to clear the air that there was self-succession. But while on it, the plot thickened to his chagrin as the campaigns heated up, a 2 million-man match gathered steam and all the political parties were adopting Abacha as their candidate in the impending election. So, he went to Abacha to kick against it, whereupon Abacha told him how he alone had spoken to him on the issue like that, an ominous censor. He pursued the matter to Gidado Idris, the Secretary to the Government of the Federation whom he regarded as principled and courageous. Gidado took up the issue with Abacha but nearly got himself sacked because “Abacha was furious with Idris and almost removed him as SGF”, (p. 44). This forms the basis of the author’s claim that if there was anybody Abacha would have punished for opposing self-succession, it would have been Idris, not any military officers whom he had the power to retire.

Notwithstanding the signposts building up, Bamaiyi expanded his lone ranger footwork against the self-succession move, this time collating and producing a document titled “The Armed Forces’ Position on the Current Development of the Transition to Civil Rule” in April 1998 which concluded, inter alia, that “at the current stage of the nation’s political development, there is an overwhelming consensus that the military should quit the political scene; the failure to do so is likely to exacerbate our ages-long political crisis”, (p. 56). This document further categorically declared how ‘the frenzied clamour’ for Abacha and his adoption by all the political parties could not interfere with the military’s programme of returning to the barracks, imploring no one in particular to encourage Abacha to respect the wishes of Nigerians “while the military demonstrates its total subordination to constituted authority by respecting the wishes of the people and their political representatives”, (p. 57).

Predictably, this infuriated what the author referred to as Abacha’s inner security men who then conveyed their own meeting attended by an air Vice Marshall, six colonels and a Major. It was this meeting that arrived at linking the COAS with an American and NADECO plot to create chaos in Nigeria; that read controversy to some posting proposals it alleged the COAS had been making; that claimed the COAS had been seizing up General Officers Commanding (GOC) the divisions on the adoption of the Commander in Chief as a consensus candidate by all the parties; how the COAS had not carried out a mandate of a meeting to discuss the adoption with Abacha. This meeting concluded that Bamaiyi was not in support of the transition programme and had become a danger to its realisation. Aside from denying each and every of these claims, Bamaiyi takes us on a journey of how this sort of thing became a feature of the military.

Col. Abubakar Dangiwa Umar, (retd): consumed by junta politics

His analysis in Chapter 12 is that everything done under Gowon to instil discipline in the military after the civil war collapsed with the coming of General Babangida in 1985. He enumerated the manifestations. One was the use of Majors to arrest the Commander in Chief and a Major-General. Not only were these junior officers used, they were given appointments far above their punching capacity, such as being posted as military governors to states such as Kaduna and Borno which were part of the 12 states structure. This category of states were hitherto governed by Major-Generals, Brigadiers and senior colonels. Thirdly, it was becoming an accepted practice for senior military officers who wanted anything to go through these Majors. And finally, when Dangiwa Umar as Commander of the Armoured Corp and School in Bauchi organised what was otherwise generally rated as one of the best of such exercises, Babangida wrote a comment that was instantly considered problematic by many senior officers who were there. By writing that if he had his way, all army chiefs of staff would be armour officers, Babangida was making a statement that could put the colonel in trouble.

Observation and familiarity with these trends since when he was a Lt Colonel and Brigade Commander predisposed him to coming up with a rule book once he had opportunity to be COAS. His rule book was titled My Philosophy of Command of the Nigerian Army and its principles provided the basis of a number of disciplinary reforms, particularly as it related to promotion and posting. But this was a move that the death of Abacha put a stop to, basically. On June 8th, 1998, the author had been in Abuja for three days on the invitation of Abacha. That morning, he was called by a Villa operator to proceed to see the Commander in Chief. The first shocker was being told at the gate that he could not go into the Villa with his security. He fought that out and went with his security. Second shocker was learning, along with other very senior government officials that excluded Jeremiah Useni, that Abacha had died. Although Bamaiyi remains convinced that Abacha died of unnatural death, he also believes that “the truth of Abacha’s death may never be known because the evidence was lost from the beginning”, (p.68). In any case, the information about Abacha’s death to this exclusive club automatically triggered a struggle for succession pitching him against Abdulsalami Abubakar. First, some middle ranking officers did not want to go to Kano for the burial of Abacha which the family wanted done quietly rather than with military honours. But an already suspicious COAS had instructed the Commanding Officer of 81 Battalion, Keffi to watch out and crush any move by any group to take over the government.

With the burial over, the struggle intensified. A group of senior officers preferred Bamaiyi to take over because they alleged that Abdulsalami Abubakar had a corruption record in his career history. Jeremiah Useni was considered to have been too pro self-succession to be considered for the job aside from insinuations that he was an accessory to Abacha’s death. And it was the uncertainty about who, between Bamayi and Abubakar, would make it that explains why both the Bible and the Koran were brought to the swearing-in. Bamaiyi not only declined, according to this book but, instead, nominated Abubakar whom he said had been distributing what looked like a ballot paper in anticipation of voting. Abubakar’s coming was the end of one chapter and the beginning of another, culminating in Bamaiyi’s tragedy – eight years in detention at first and then the vindication he speaks of.

What a long but permanently interesting tour! But, a tour which throws us immediately into a politics of meaning. In other words, what can we make of Bamaiyi’s account? Was his the price for nobility of character, the character of being above politics, of independent mindedness and an idealist risk taker or a case of a commander whose lack of tact bordered on foolhardiness close to Murtala’s? If it was none of the above, then could he have been a victim of his identity? Or was it just junta politics or still, a case of power deciding truth? Questions, questions and questions. But questions which we do not need to bother ourselves for the answers because there are no such answers. The question of right versus wrong, true and untrue and such other binaries belongs in the world of the simplicita.

What we can say and what we need to say from the point of view of the emancipation of Nigeria is that General Bamaiyi has done Nigeria one more wonderful service by enriching the accounts of the period we are dealing with. The Vindication of a General is, therefore, a very welcome addition to existing claims and conflicting voices on that chapter of Nigerian history. It is on that multiplicity of voices that Nigeria’s progress would rest. That is in the sense that it is in the continuing interpretation and re-interpretation of this multiplicity of voices that we would find the right beacons in the struggle to reconstitute the Nigerian State and society along a much more emancipatory trajectory than the mess that some of her best trained military officers have made of it. In other words, we do not need a once and for all interpretation of the story in The Vindication of a General because there cannot be one anyway. The way the book is understood in 2016 is not the way it would be understood in 2026 or any other time in future. Our children will interpret it differently from the way we do today.

While, therefore, imploring all readers to take note of General Bamaiyi’s entry point and the entry points of those who gave similar or related accounts before him, we should also call on other central actors in all such drama to come forward with their own versions of how a nation was made a football in power game. By doing so, they would not only be healing the wounds they endured but also the wounds they inflicted on the society. Someone such as General Obasanjo has set a good record in this regard by always writing an account of his own role in all these. Doing so by all who played crucial roles in the unfortunate drama under reference will contribute immensely to the healing dialogic requirement for the transformation of Nigeria in the first half of the 21st century.

Mr Onoja, a member of the Editorial Committee of Intervention, teaches Political Science at Veritas University, Abuja

1 Comments

Habila Bala Dusssah

Good day, Please how do I obtain a copy of the book by General Ishaya Rizi Bamaiyi?