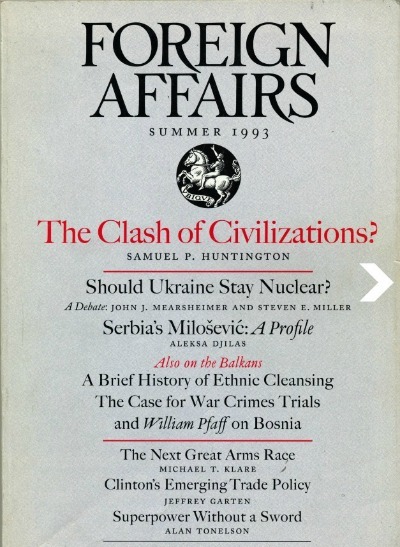

The book, The ‘Clash of Civilizations’ 25 Years On: A Multidisciplinary Appraisal has been published on twenty five years of about the most controversial and the most contested theory of conflict ever in its reading of post Cold War world order in terms of clash of civilisations or cultures. That’s Samuel Huntington’s ‘Clash of Civilisations’ about which the all time question remains whether he was preparing the ground for something like the ‘global war on terror’ or he was just being a brilliant political scientist. The claim which is invoked in explaining every silly conflict today is now engaging the attention of big names such as John Mearsheimer, Ian Hall, Francis Fukuyama and a whole lot of Realists as well as their intellectual enemies. Here, a reviewer peeps into what is in it for E-IRs from where it has been reproduced as follows:

By Davide Orsi

Prof Huntington at a session of the World Economic Forum before his death in 2008

Over the past 25 years, Samuel P. Huntington’s article ‘The Clash of Civilizations’ (1993) has shaped public opinion and the ways in which the academic world thinks about world politics. Events in the Middle-East and Asia, American military interventions, the Ukrainian conflict, the refugee crisis in the Mediterranean, Brexit, the rise of far-right movements in America and Europe challenge our traditional frameworks and seem to show the persistent relevance of the controversial notion of a clash between opposing and incommensurable values, religions, cultures and beliefs. That article, written in 1993, still seems to provide, in particular to the public opinion, a paradigm through which to interpret our times.

The purpose of this collection is to offer a critical analysis of Huntington’s contentious ideas and to appraise its relevance to the understanding of today’s political context. The book aims to be both a guide for students looking for an introduction to the notion of a ‘clash of civilizations’ and a point of reference for scholars interested in the debate provoked by Huntington’s work. The collection does not present a single univocal interpretative line, but it rather offers different approaches and perspectives. Some contributors stress the persistent relevance of the ‘clash of civilizations’ thesis, others praise its importance for the study of international relations, others advance a strong and polemical criticism.

Already in 2013, E-IRs published a collection on the ‘clash of civilisations’ to discuss Huntington’s legacy. Different from that book, this collection contains longer essays and has a stronger multidisciplinary character. Contributors have indeed considered the ‘clash of civilizations’ thesis from the point of view of different disciplines: International Relations, Political Science, International Law and Political Theory.

The book version

The structure of the book reflects this multifaceted and eclectic approach. A first series of contributions examines the theoretical content and legacy of Huntington’s ideas. Chapter one provides a sort of introduction to the thesis defended by Huntington in the 1993 article and in the 1996 book. To this end, it illustrates the philosophical root of their arguments by placing the theory of the ‘clash of civilizations’ in the context of the realist tradition in international political thought. In Chapter two, Ian Hall focuses on the concept of civilization by comparing Huntington’s theory to Arnold J. Toynbee’s. Hall underlines some of the similarities between the two thinkers, especially in their aims and assumptions, but also some of their important differences, with particular regard to their divergent accounts of the relationships and encounters between civilizations. In his essay (Chapter three), Erik Ringmar advances a much more polemical interpretation of Huntington’s idea on the ‘clash of civilizations’, linking it to a quintessentially American way of relating to other civilizations.

In their contribution (Chapter four), Gregorio Bettiza and Fabio Petito consider the rise of discourses, institutions and practices built on the premise that civilizations and inter-civilizational relations matter in world politics. They show that the ‘clash of civilizations’ paradigm advanced by Huntington is not the only possible kind of civilizational analysis of international politics. Moreover, they defend the critical potential of civilizational approaches in a time of crisis of both national identities and liberal universalizing projects. Jeff Haynes (Chapter five) explores the relevance of Huntington’s ideas for the understanding of the world after the end of the Cold War, and its importance for the ‘return to religion’ in International Relations. At the same time, Haynes highlights how in the years after 9/11, and also in response to Huntington’s thesis, there has been a rise in attempts of inter-civilizational dialogues, which are now facing new challenges.

Paradigms wish to explain the world and there is no doubt that with his article and book Huntington wanted to offer an instrument for the understanding of international politics in the twenty-first century. Focusing on an often-neglected aspect of Huntington’s work, Kim Nossal (Chapter six) examines the idea of ‘kin-country rallying’ and argues for its relevance to the understanding of international affairs. This notion, much less famous than that of clash of civilization, also characterizes Huntington’s paradigm and claims that states are part of civilizations and behave like kin. This theory, argues Nossal, explains the relations among some countries much better than traditional international relations theory.

Foreign Affairs did not forget when the theory was 20 years old. Now, it is twenty five years old

In Chapter seven, Glen M.E. Duerr compares the predictions made by Huntington, Fukuyama and Mearsheimer on the world after the end of the Cold War, with particular regard to the rise of ISIS, the wars in the Middle-East, and the Ukrainian crisis. This latter case is of particular interest because Huntington seems to offer contradictory statements on the possibility of a conflict between Russia and Ukraine over Crimea and the eastern part of the country. The contribution by Anne Khakee (Chapter eight) also examines the Ukrainian case and advances a criticism of Huntington’s civilizational analysis. Khakee argues that the current crisis between Russia and Western powers can be explained by looking at them as clashes between alternative political systems, not civilizations. Chapter nine by Anne Tiido is also devoted to the case of Russia and of its foreign policy. Tiido instead underlines the role of the idea of civilization in Putin’s discourses and actions as well as in Estonian political life after the end of the Soviet Union.

These contributions examine the relationships between Russia and its neighbors, showing both their shortcomings and potential. Chapter ten, by Ravi Dutt Bajpai focuses on a non-Western context and on the relationships between China and India. Bajpai examines how the self-perception of being ‘civilization-states’ has shaped the national identities and bilateral relations between the two countries. Wouter Werner (Chapter 11) writes on an often neglected aspect when appraising the impact and the relevance of Huntington’s thesis: that of its influence on the study of International Law. Werner considers this in the case of the actions of the International Criminal Court in Africa and explores how arguments about civilizations are used to counter cosmopolitan claims on human rights and international society. Werner shows that the idea of a ‘clash of civilizations’ is important in contemporary normative debate on international law and justice.

As already mentioned, Huntington’s thesis has also had a huge impact on the public debate, especially over issues related to multiculturalism and relationships with religious minorities. In Chapter 12, Ana Isabel Xavier explores the current migrant crisis in the Mediterranean and its perceived link with a ‘clash of civilizations’. She also considers the impact of this crisis on the policies of the European Union and on the future of the European project. In Chapter 13, Jan Lüdert sheds light on the use of the image of the ‘clash of civilizations’ by far-right movements in the European political context, by examining the electoral success of Alternative for Germany (AfD) in the 2017 German general elections. Lüdert offers a detailed account of the impact of Huntington’s ideas on AfD’s political position and rhetoric, with particular regard to the refugee crisis and the relationship with Muslim communities.

As is already clear from this short introduction, the volume offers a rich analysis of Huntington’s ideas. It presents the most important arguments and ideas grounding the idea of a ‘clash of civilizations’, it examines the validity of that thesis for the understanding of international affairs and international law in contemporary world politics, and discusses its persistent relevance in the public debate.