At 434 pages, including the index, it is a hefty book but a pleasurable text to consume. Just published this week, it is written in simple English and at a bold enough typeface, it is very friendly to the eye. No one can predict now which set of potential readers will patronise it more – the ordinary or general interest readers such as journalists, politicians and the business elite on the one hand and the experts such as students and researchers of Nigerian Government and Politics, African Politics, Sociology of the Military, Politics of Development, the State, Military in Politics, Political Realism and Political Sociology on the other hand. While the synthesis of the flow of politics of power makes it a compact reference book for everyone, the two key issues under focus are each inviting in themselves. The dominant subject matter is, of course, the puzzle of enduring democracy in Africa but this is seen from the lens of civil-military relations. In other words, there is a question around which the book revolves: what is it that explains why the military has contested the democratic space with professional politicians across Africa contrary to the construction of military rule as a critique of the norm?

Prof Elaigwu

The mindset of the author appears to be that this is the time to reflect on the poser when direct military intervention in Africa has receded in Africa in spite of what the Zimbabwean military did at the close of 2017 in relation to the subject of enduring democracy. And so, using Nigeria as a case study, Prof Elaigwu swaggers intellectually into the arena with a broad sweep of each and every administration in the postcolonial history of Nigeria, interrogating and decentering many sacred cows, established truths and commonsense conclusions.

The heartland of the book might be located in the author’s take-off point in the Preface with Africa being caught in another global frenzy – the democratic fever in the post Cold War, a process the West is leading even as its expectation of planting democracy in Africa in the aftermath of the ‘wind of change’ collapsed, giving way to the rise of the lumpen militariat, Ali Mazrui’s concept for the first generation of military rulers who signified contestation of state power with the civilians across Africa. Interestingly, the West clapped hands for them but only for the military, like the politicians, to also fail the test of transforming Africa. So, what is the future of democracy in Africa, especially Nigeria? What exactly is democracy in the first case? Is it elections? Is a civilianized polity as has happened across West Africa – Ghana, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, Gambia – a democratic polity? Have the African elite learnt from the past? If it has not, what are the arrangements to make them learn?

Locating the tension between civilian and military elite in the re-arrangement of state processes with the transformation from what Ali Mazrui calls the Warfare State to the Welfare State in human history, Elaigwu argues that the African peculiarity of that tension is a crisis of institutional transfer. That is how the military, like the other modern political institutions – political parties, the legislature, the Judiciary – was exported to Africa during the terminal point of colonial rule sans the values underwriting it, the value of civilian supremacy. Its elite, like the political elite, had not digested the logic. In other words, the military as an apolitical space had not been internalised by its African elite just as the politicians had not internalised the logic of political parties, the legislature or the spirit of politics as a game. Instead of a game, the political elite turned it into a battle. The poor domestication of the logic of the military profession after the era of state consolidation through conquest, (the Warfare State) which is the subordination to civilian control once the state transformed into a welfare machine across the world explains direct intervention in the African context, injuring democracy very badly. The author sees a dark cloud over democracy unless and until this domestication is sorted out.

This is the argument he deploys data to substantiate in the African context even as the military intervenes in politics everywhere else, including advanced democracies. Section one of the book treats that aspect in three chapters, drawing out the different kind of ways by which the military pulls itself up in the politics of power. Elaigwu’s handling of it is a beautiful rendition on civil-military relations, a theme dear to traditional political science. Section two, made up of six chapters, is where he focuses on Nigeria as his African case study on the subject matter. It means a sweeping stroll from the First Republic through the Ironsi, Gowon, Murtala, the Obasanjo regime, the Shagari regime, the Buhari regime, Babangida, Shonekan, Abacha and Abdulsalami regimes between 1960 and 1999.

A defining feature of the repertoire is the military dominance in power. But before the military, there was the First Republic. Although it is not an issue treated in the book in its own right, the quick reference to it questions the assumption that Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa had no mind of his when the Sardauna was involved.

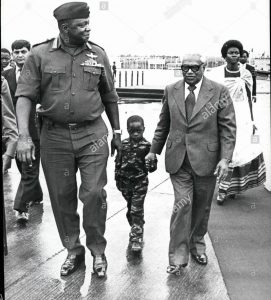

Field Marshal Idi Amin Dada then of Uganda, a member of the Lumpen militariat

One major rupture in section two is the reason given hitherto for the choice of federalism by Nigeria’s founding fathers. Contrary to the notion that they did so because they understood federalism as the best mechanism for managing diversity, this book says it was the intense ethno-regional rivalries between them or what Elaigwu calls “parochialism based on awareness of others in the competitive setting” that made them do it, (P.77). Linked to that is the argument that “A federal structure in which the Northern Region accounted for 79% of the total geographic area and 56% of the population made groups from the Southern regions to feel seriously disadvantaged”. So, the book tells us the bases for today’s calls for restructuring at the expense of a national business model even when the constitution has offered one in its Chapter Two.

Are there any central characteristics? Ironsi whose was the first military regime declared the discomfort of regime with running what he called five governments. He was referring to the four regional governments and the centre, signposting the military’s centralising impulse. One other interesting item in the sweep is how common to both Ironsi and Gowon the idea of tenure specification. While Ironsi set aside three years, Gowon set three months. Did it suggest that the military could rarely estimate the enormity of the problems at each intervention? One poser in the narrativisation of Ironsi is why he opted for the Unification Decree when neither the Francis Nwokedi Commission on the harmonisation of the civil service nor the Rotimi Williams Committee on constitutional review had submitted a report.

The author brings out an element of the tension between the military and the civilian elite under General Gowon on pages 102-3 in the sort of analysis that “while the ordinary people did not care who ruled them, military or civilian, as long as they were provided with water, electricity, education, health services, food, good roads and other services, the elite cared very much”. The elite cared because, as Mallam Aminu Kano was quoted to have said in 1974, “If your economic planning is not influenced by your political thinking, you are bound to make a mess of it”. Aminu Kano spoke in 1974, Gowon fell in 1975. It all takes us to the military’s fixation with announcing transition time table always as an element of the politics of power.

Chapter six is a comprehensive treatment of the key issues in Nigerian federalism in the Second Republic from the pen of the only scholar of federalism to run a Federal Government think tank on federalism. There is an interesting portrait of General Muhammadu Buhari as military Head of State. It says “Buhari was a military ruler who emphasised law and order, with a streak of intimidatory style”. The assertion was drawn from Buhari’s long jail sentences for politicians, his decrees, his reaction to freedom and democracy and his never announcing a political programme.

There is a rather comprehensive recap of the Babangida junta of which the author was part of the intellectual crew in addition to Professors Jerry Gana, Oye Oyediran, Bolaji Akinyemi, Ikenna Nzimiro, Tunde Adeniran, Sam Oyovbaire, Omo Omoruyi, among others. He described Babangida’s transition as a long programme but “with all kinds of ingenious attempts to create local democratic institutions and processes”. Is it possible that is what the scholars around power thought they were doing?

A lot of readers would pay attention to page 229 to see if they could deconstruct the quotation from Omo Omoruyi as to whether Babangida and Abacha sealed a deal to succeed each other. It is a powerful quote on the relationship between IBB and Abacha but for whom IBB and his family, according to the quote, would have been wiped out during the Orkar coup but without Abacha taking over from the man he called by his name, Ibrahim.

Prof Elaigwu refreshes our memories of the roll call of callers on Abacha to succeed himself, calling Segun Adeniyi’s compilation of a fuller list an interesting reading. Of course, he also refreshes our memory of those on the barricades protesting any such attempt, including his own lecture in Lagos eight days before Abacha’s demise and in which he told the General that none of the plausible models would work. But even more interesting is his recall of those who were inviting Abacha to overthrow Shonekan in the assumption that Abacha would rule briefly and handover to Abiola. And here is this: Did Shonekan trigger the coup that removed him by moving from Aguda House to the Presidential Villa, thereby breaking a ‘gentleman agreement’? This is not a theme treated in its own right but came by way of supplementary information, (P. 257).

Part two of this review will take section three of the book which looks at 1999 to date in relation to enduring democracy in Africa, using Nigeria as case study. Two controversies that might arise are these. One is Prof Elaigwu’s conception of democracy as no more than public authority popularly obtained; the institutionalisation of the rule of law; the legitimacy of rulers; choices and accountability. Would those that Peter Gowan, the late British political economist called the business democrats who control Wall Street in favour of ‘Business Democracy’ be able to abide by this definition? The second question some readers might confront the author is if there isn’t a contradiction between his declaration that democracy is universal but that its tenet have to be domesticated in Africa?

Finally, the few typos noted in spite of the excellent production work, the most prominent being the appearance of PDP in the result sheet of the General Elections in 1979, (P. 124) and the use of ‘elect’ rather than election on p. 126.