Was President Muhammadu Buhari too overwhelmed to do anything about it or didn’t care a hoot or even took it as what God had ordained to pass? For, there is no way he would not have anticipated the current ‘Vote of No Confidence’ on him around Nigeria because, by September 2016, the warning shots had been fired.

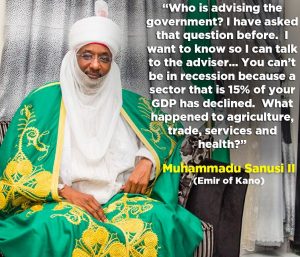

Intervention’s list of those who had opened fire on the president by then in the report titled “Chinua Achebe’s Arrow of God for President Buhari?” (September 3rd, 2016) included Dr. Junaid Mohammed who criticised the president for having only antiquated ideas. Muhammadu Sanusi 11, the Emir of Kano first criticised the president or the government for refusing to deregulate the forex market officially, a point he drove home more forcefully then with a very dramatic implication of that policy direction. Professor Charles Soludo, his predecessor in the Central Bank of Nigeria asked the regime to stop looking back and face the future. Professor Ango Abdullahi had attacked the president, decrying the quality of his cabinet. The now late Lawal Kaita, from the president’s home state of Katsina told Saturday Sun, (August 13th, 2016, p.5) that he was yet to see Change. “The good change we expected, we are not getting. We are getting bad changes”, he had said.

Intervention’s list of those who had opened fire on the president by then in the report titled “Chinua Achebe’s Arrow of God for President Buhari?” (September 3rd, 2016) included Dr. Junaid Mohammed who criticised the president for having only antiquated ideas. Muhammadu Sanusi 11, the Emir of Kano first criticised the president or the government for refusing to deregulate the forex market officially, a point he drove home more forcefully then with a very dramatic implication of that policy direction. Professor Charles Soludo, his predecessor in the Central Bank of Nigeria asked the regime to stop looking back and face the future. Professor Ango Abdullahi had attacked the president, decrying the quality of his cabinet. The now late Lawal Kaita, from the president’s home state of Katsina told Saturday Sun, (August 13th, 2016, p.5) that he was yet to see Change. “The good change we expected, we are not getting. We are getting bad changes”, he had said.

On August 29th, 2016, Cardinal Anthony Okogie entered the fray through an open letter which touched on most of the issues bogging people’s minds – the overarching direction of the government vis-a-vis the reality of misery on the ground, the quality of the cabinet, non-inclusiveness, selectivity in anti-corruption war, social transformation with particular reference to the implication of over-administration of education therein. That was an ecclesiastical voice. Others such as Bishop Mathew Hassan Kukah had earlier on described the anti-corruption war as misplaced because corruption itself is a manifestation of a deeper rottenness. The Nigeria Labour Congress, (NLC) described Buhari’s policies as anti-workers. There was also a group made up of Ebenezer Babatope, Abubakar Tsav, Pat Utomi, Olisa Agbakoba, Junaidu Mohammed, Lee Maeba and Frederick Fasheun who told the president to intervene or the country could shut down (Vanguard, August 11th, 2016). Others such as Reverend Father Mbaka, Najatu Mohammed and Kano emir had equally drawn attention to one variant or the other of such possibility.

Even members of the upper crust of the establishment who had been trooping to the seat of power seem frightened or concerned too. It showed in how each of General Gowon, Obasanjo, Abdulsalami, Professor Wole Soyinka and Pastor Tunde Bakare who came out of meeting with the president always asked the people to be patient and to assure that Buhari would not disappoint. They were all implying that there was problem on the ground since patience is only applicable to something late in coming.

That must have been the foretelling of turbulence ahead after which the nation went to the drawing board. Not only did advocacy for restructuring acquire currency, other results are now coming out from the drawing boards with reference to who takes power that is now believed to be lying on the ground to be taken in 2019. One of the most prominent contenders so far is Obasanjo’s Coalition for Nigeria, (CN), which is yet to unfold but which is an anti-thesis of the Nigerian crisis of leadership, power and governance and from which a synthesis is bound to emerge. What the synthesis would be would depend on the class, regional and even ideological balance of forces. Next to it is a caucus approach now in the air by which a consensus presidential material that can resolve the elite fragmentation in the North as well as bring freshness to Nigeria in 2019. Then there is what can be called the Middle Belt bid for power. The Middle Belt thinks it is its turn to produce the next president of Nigeria. This is no longer a behind-the-scene kind of politics as it is already being massively circulated via whatsapp messages with names that can be located.

Gen Yakubu Gowon, Nigeria’s war time military leader

The Middle Belt is making a claim to holding the ace in re-inventing leadership, power and governance in Nigeria. Less emotively put, its main animus seems to be the locational concentration of Nigerian leaders from the North which it is basically saying that this is the time to do something about. For it, it is time to correct whatever coincidences might account for the situation whereby, except Tafawa Balewa and General Gowon, the rest are all from one axis of the North: from the legendary Ahmadu Bello to Murtala Mohammed, Shehu Shagari, Muhammadu Buhari, Ibrahim Babangida, Sani Abacha, Abdulsalami Abubakar, Umaru Yar’Adua and Muhammadu Buhari. Interpreting this now as a critique of democracy and a project of exclusionary intent, it is emphasising how desirable to demonstrate that there is no truth whatsoever in an agenda of deliberate and purposive exclusion of others from the pains and pleasures of serving Nigeria at the level of the Office of the president.

Beyond the whatsapp messages, its other strategies are still unclear. Is it its flirtations with extra-regional blocs or the sort of approach the larger North used in 1978? In 1978, the North asked the South to be allowed to take the first shot at the presidency on the return of democracy in 1979. And the South obliged. So, is a cool headed Middle Belt leader going to ask the larger North to grant him the concession to produce a presidential material for 2019?

There is a hint to that effect although it is only being implied from a different argumentation itself. It is the argument about how General Danjuma would have been the sort of person suitable for Nigeria in 2019. Some Middle Belt cadres would say that if General T Y Danjuma were still 62 -67 years of age, the option would have been to camp in front of his house and pile irresistible pressure on him to purchase presidential contest form of any party with a view to taking up leadership of Nigeria at this point in time. It is not so much that they think he is an angel. What is suggested is that he is not the sort of person who will sublet power to any cabals. He is his own cabal, his own godfather and adequate in himself in many respects. They also speak of Gen. Danjuma having no history of being overwhelmed by any office he has held. Unfortunately, in their own words, T Y is now 80. The belief now is summed up in the notion that “if Mugabe was still running the show at 93, then T Y can oversee the next president of Middle Belt origin for the next four years from a distance in case such a fellow begins to mess up”.

It is a very emotional issue at some point, with lush references to how he had once said he would not mind putting on the uniform again to fight to keep Nigeria one. As they would not want to see an 80 year old combatant, they are imploring him to gather the energy and enthusiasm to defend Nigeria Now by ensuring that Nigeria’s democracy is cured of its multiple sites of nation destroying madness. This argument is the basis of the suspicion that something must be cooking about General Danjuma asking the larger North for a concession to produce a presidential material in 2019. Only God would know who that material might be now. That is if the deduction from the above conversation is anything to go by.

What about those who might be disadvantaged by the exclusionary implication of a predetermined outcome in this exercise in micro-zoning? This does not appear much of a problem to some of the Middle Belt cadres who would argue that such persons should borrow a leaf from what they say Northern leaders did in 1998. That is how established politicians such as Adamu Ciroma, Umaru Shinkaffi; Bamanga Tukur; Lema Jubrilu and one or two more others sacrificed their ambition by not contesting against Obasanjo in 1999. If they did, so the narrative goes, they would have delayed the onset of democratisation because Obasanjo would not have won in Jos Convention of the PDP.

Gen T Y Danjuma: The last of the bridge builders?

The Middle Belt is as complex as it can be. It is so complex in the terms and senses in which identity is discussed today – ethnicity, homeland, religion and culture. The sense in which it is being invoked though is more of a Christian sense of the collective self and a strong, residual antipathy to those the British made overlords in the affairs of the old Northern region. The problem is that nobody has anticipated, much less operationalised a transitional justice approach to managing the structural crimes of colonialism. It was just assumed that the modern state would heal all wounds. It was about to do that but Cold War politics made that impossible and the new states in Africa were subjected to conditions in which it could not even contemplate sorting itself out internally, such as addressing the problems of identity and identity politics.

Bill Clinton once said that the “US cared more about how African nations voted in the United Nations than whether their own people had the right to vote”. He got it 100% correct. In that sort of situation, state legitimacy as a product of inclusivity becomes a luxury. It leaves some people permanently grumbling. Nigeria responded to that though in a very acrimonious, chaotic manner in 2011 when it elected Dr Goodluck Jonathan as president. Dr Goodluck messed up the battles but magically won the war by standing for peace in giving up power when, according to President Buhari, he could have caused trouble. It was not the type of elevated decision a Jonathan was expected to pull through. Wherever the initiative came from, he has secured his own future with that singular move, leaving people in a counterfactual wilderness as to whether Buhari would have done the same if he were the one. The question, however, is whether Nigeria is about to respond to another of the historically instigated grumbling in the polity but, perhaps, with less acrimony as in 2011?

Depending on how it is handled, this could be a resolution of the stalemate in the North from where Nigeria’s threats are now concentrated – violent conflicts of ethno-religious and native/settler sparks, Boko Haram insurgency and now herder violence, with no one knowing what next.