Nigeria is going through what the president himself calls “needless fuel queues”. It is not such a new experience for Nigerians except that this one is coming after the May 2016 increase in pump price of fuel from N86. 50 to N145 even though Buhari as President-elect had said subsidy is a fiction. It is interesting that, this time, no one is hearing of any reference to any set of cabals or another in the explanation of the crisis. Although the government is saying that independent marketers are the culprits this time, independent marketers do not invoke the mystery of cabals. It would remain a puzzle for quite some time how the government of the day lost this Fuel War on all sides in that respect. But that is at the top.

Nigeria is going through what the president himself calls “needless fuel queues”. It is not such a new experience for Nigerians except that this one is coming after the May 2016 increase in pump price of fuel from N86. 50 to N145 even though Buhari as President-elect had said subsidy is a fiction. It is interesting that, this time, no one is hearing of any reference to any set of cabals or another in the explanation of the crisis. Although the government is saying that independent marketers are the culprits this time, independent marketers do not invoke the mystery of cabals. It would remain a puzzle for quite some time how the government of the day lost this Fuel War on all sides in that respect. But that is at the top.

The pity here is the collapse of the assumption that President Buhari’s previous involvement in the global oil commodity politics as a former Nigerian Oil Minister positioned him to take Nigeria out of the oil entrapment once he settled down in May 2015. Instead of doing so aggressively, the president is busy searching for oil everywhere even though oil has no chance of taking any African country from the bottom of the global pit, no matter the amount of it found. It is not about prudence or patriotic management of it. It is simply that oil is a paradoxical commodity. It will always be about corruption, violent conflict, environmental degradation, diversion from agriculture and poverty because only very few people get involved in it.

Africa’s most entrenched thinkers and actors in the global policy mill know this and they have said it that oil is following the career of gold. An inherently volatile global politics could raise the price now and then, that changes nothing. The global oil market will even be worse for countries in Africa now that the world is moving from unipolarity to a polycentric configuration of global power in which almost all the old and new global powers are also global energy powers. And power matters in everything, more so in oil. It would be interesting to know who advises the Nigerian president on the political economy of energy policies in the emerging world.

See how everyday narratives frame the fuel scarcity as APC’s convention across the country

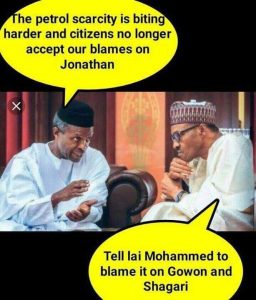

Another of the street wise creativity on the crisis. The pattern of circulation makes it difficult to give credit fro this graphic but it would be corrected as soon as ascertained

Meanwhile, everyday narratives of what is going on are springing up, with its own implications for citizens-state relationship. It should surely interest the government how the crisis is understood by the people below, irrespective of how the government itself understands the crisis – whether as a product of its own inattention to signals or sabotage of one set of cabal or another or of ‘corruption fighting back’ or the futility of neoliberalism or whatever else by which this ugliness is understood.

What is the guarantee that ordinary Nigerians would not become collateral victims of the 2018-19 power tussle in which ‘natural’ or ‘artificial’ scarcity of fuel might be a legitimate weapon?