In a major report it is calling the first of its kind, the United Nations Development Programme, (UNDP), is reinforcing the view that poverty is what radicalises young people into extremism as seen in Al-Shabaab and Boko Haram. Titled Journey to Extremism in Africa: Drivers, Incentives and the Tipping Point for Recruitment, the 128 page document was released September 7th, 2017 but somehow, it does not appear to have been widely reported in the media. Intervention stands to be corrected but Google check did not show its publicity.

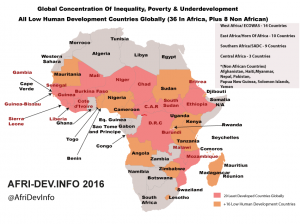

A map of Africa showing distribution of poverty

By its own profile of the report, it presents the results of a two-year UNDP Africa study on recruitment in the most prominent extremist groups in Africa. According to the UNDP, the study reveals a picture of a frustrated individual, marginalized and neglected over the course of his life, starting in childhood. “With few economic prospects or outlets for meaningful civic participation that can bring about change and little trust in the state to either provide services or respect human rights”, the study suggests, “such an individual could, upon witnessing or experiencing perceived abuse of power by the state, be tipped over the edge into extremism”. It goes on to say that the study is an alarm bell on Africa’s vulnerability to violent extremism and how it is deepening.

Contrary to the widespread belief that religion serves as the springboard for extremism, the UNDP data suggested strongly that religion could and did act as both a prompter and a restraining factor. “The data shows that contrary to popular narratives, those who join extremist groups tend to have lower levels of religious or formal education and less understanding of the meaning of religious texts”. “Although more than half of respondents cited religion as a reason for joining an extremist group, 57 percent of respondents also admitted to understanding little to nothing of the religious texts or interpretations, or not reading religious texts at all”.

The study, therefore, concluded that the extremists might not even have embarked on that course if they understood what the religion is saying. The study put it this way, “understanding one’s religion can strengthen resilience to the pull of extremism: among those interviewed, receiving at least six years of religious schooling was shown to reduce the likelihood of joining an extremist group by as much as 32 percent” What this suggests is that religion in itself did not prompt radicalism until either the youths were manipulated by somebody or by poverty.

A specie of African insurgents

The evidence that suggests that poverty rather than religious convictions propelled insurgencies in Africa can be interpreted as an admission that distressing and incomplete modernisation is to blame for fanaticism and bigotry across Africa. In Nigeria, for instance, that is a conclusion many would accept just as many would reject it. For if that is correct, it means all explanations which see Boko Haram as a product of external machinations or internal elite complicity fall flat. That would be contrary to the argument that traces Boko Haram to great power geopolitics in global borderlands. A former Nigerian security chief has even written and published a paper to the effect that Boko Haram is nothing but such geopolitics as well as the accumulation of insurgents from the theatres of war such as Chad, Sudan, Chechnya, Mali and lately, Libya.

The study is thus bound to be a subject of contestations. If the elite complicity or external links are dismissed, then it has to be accepted that neoliberal Structural Adjustment Programme, (SAP) has, indeed, led Africa into a hell hole and about which the UNDP is simply being frank.

To Abdoulaye Mar Dieye, the UNDP Africa Director who launched the document at the United Nations headquarters is credited the point that “Borderlands and peripheral areas remain isolated and under-served. Institutional capacity in critical areas is struggling to keep pace with demand. More than half the population lives below the poverty line, including many chronically underemployed youth.”Continuing, he said the development issues were delivering services, strengthening institutions, creating pathways to economic empowerment, adding that there is an urgent need to bring a stronger development focus to security challenges.

Pope Francis speaking for the poor as the passport to paradise the day before yesterday, bringing his moral authority to bear on global activism for emancipation from poverty and structural violence against the world’s majority

Based on a methodology of interviewing hundreds of extremists, the UNDP says the study pinpoints key factors triggering decisions to join violent extremist groups in Africa and lists them as deprivation and marginalization, underpinned by weak governance. “Based on interviews with 495 voluntary recruits to extremist organizations such as Al-Shabaab and Boko Haram, the new study also found that it is often perceived state violence or abuse of power that provides the final tipping point for the decision to join an extremist group

In the study’s own words, “participants in the study were asked about their family circumstances, including childhood and education; religious ideologies; economic factors; state and citizenship; and finally, the ‘tipping point’ to joining a group. Based on the the responses to those questions, the study has determined that:

- The majority of recruits come from borderlands or peripheral areas that have suffered generations of marginalization and report having had less parental involvement growing up.

- Most recruits express frustration at their economic conditions, with employment the most acute need at the time of joining a group. Recruits also indicate an acute sense of grievance towards government: 83 percent believe that government looks after only the interests of a few, and over 75 percent place no trust in politicians or in the state security apparatus.

- Recruitment in Africa occurs mostly at the local, person-to-person level, rather than online, as is the case in other regions – a factor that may alter the forms and patterns of recruitment as connectivity improves.

- Some 80 percent of recruits interviewed joined within a year of introduction to the violent extremist group – and nearly half of these joined within just one month.

- In terms of exiting a violent extremist group, most interviewees who surrendered or sought amnesty did so after losing confidence in the ideology, leadership or actions of their group”

In what the study describes as one of its most striking findings, 71 percent of recruits interviewed said that it was some form of government action that was the ‘tipping point’ that triggered their final decision to join an extremist group. And the actions most often cited were government actions including killing or arrest of a family member or friend.

As part of UNDP’s awareness building on the human cost of violent extremism, it is accompanying the study with a new book and photo exhibition. The book is titled Survivors: Stories of survivors of violent extremism in Sub-Saharan Africa featuring photographs and stories documented in 2016 across six African countries that have been directly affected by violent extremism. These are Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, Somalia and Uganda. UNDP’s estimates is that some 33,300 people in Africa have lost their lives to violent extremist attacks between 2011 and early 2016. It credits Boko Haram’s operations alone with resulting in the death of at least 17,000 people and contributing to the displacement of a further 2.8 million people in the Lake Chad region. There is also a claim that violent extremist attacks have affected tourism and foreign direct investment in countries such as Kenya and Nigeria.