The History They Want Us to Forget

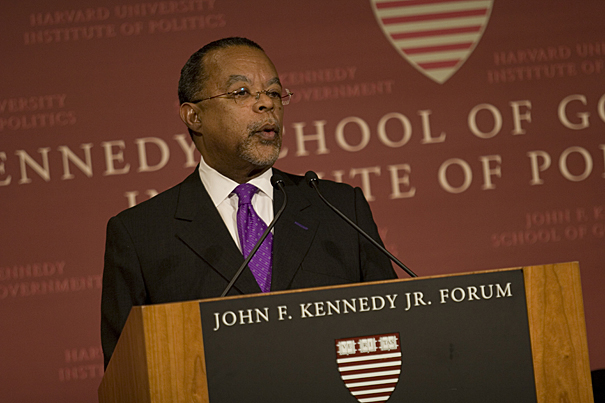

By Henry Louis Gates Jr.

Originally published February 4th, 2017 by New York Times under the title “The History the Slaveholders Wanted Us to Forget”, this piece by Henry Louis Gates Jr, the African-American film-maker and academic is republished here for the significance of its narrative – editor.

Writing in 1965, the distinguished British historian, Hugh Trevor-Roper, argued against the idea that black people in Africa had their own history: “There is only the history of the Europeans in Africa,” he declared. “The rest is largely darkness.” History, he continued, “is essentially a form of movement, and purposive movement too,” which in his view Africans lacked.

Trevor-Roper was echoing an idea that goes back at least to the early 19th century. But it wasn’t always this way. When the young Prince Cosimo de Medici (1590-1621) was being tutored to become the Duke of Tuscany — about the time that Shakespeare was writing “Hamlet” — he was asked to memorize a “summary of world leaders” that included Álvaro II, the King of Kongo, along with the Mutapa Empire and the mythical “Prester John” of Ethiopia. Soon, however, even that level of knowledge about African history would be rare.

Trevor-Roper was echoing an idea that goes back at least to the early 19th century. But it wasn’t always this way. When the young Prince Cosimo de Medici (1590-1621) was being tutored to become the Duke of Tuscany — about the time that Shakespeare was writing “Hamlet” — he was asked to memorize a “summary of world leaders” that included Álvaro II, the King of Kongo, along with the Mutapa Empire and the mythical “Prester John” of Ethiopia. Soon, however, even that level of knowledge about African history would be rare.

Perhaps it shouldn’t surprise us that ideas about Africans and their supposed lack of history and culture were used to justify the enslavement of millions of Africans throughout the New World, especially during the 19th century when sugar production was reaching a zenith in Cuba and cotton was making growers and manufacturers rich. What is surprising is that these ideas persisted well into the 20th century, among white and black Americans alike.

When I was growing up in the 1950s, Africa was the shadow that both framed and stalked the existence of every African-American. For some of us, such as Paul Cuffee and Marcus Garvey, it was a place to venerate, a place to escape the horrors of slavery and Jim Crow. For so many others of us, however, it was a place to run away from. After all, scholars such as the sociologist E. Franklin Frazier insisted that the horrors of bondage and the trans-Atlantic crossing had severed any meaningful cultural or religious links between black folks on either side of the ocean, when in fact enslaved Africans brought with them their religious beliefs, music and ways of seeing the world.

When I was a child, one of few insults between black people more devastating than the “n-word” was to be called “a black African.” Far too many of us had been brainwashed into believing that the darkness of the skin of the stereotypical African on stage and screen reflected the darkness of the cultural and intellectual soul of an entire continent of people, the continent of our ancestors.

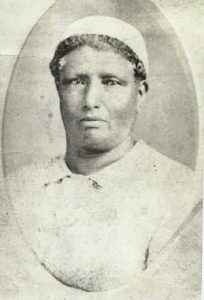

Almost all African-Americans descend from black people who managed, somehow, to survive the Middle Passage and the soul-crushing ordeal of slavery, America’s “peculiar institution,” as it was called in the 19th century. My oldest ancestor in the Gates line is a woman named Jane Gates, who was born in 1819. She was a shadow, too. I first saw her portrait in 1960, when I was 10 years old. Unlike her mixed-race descendants, she looked “African,” we thought, so that’s how we referred to her: Jane Gates, the African.

Jane Gates, the oldest ancestor in the Gates line was born in 1819. Credit: Gates Family Photo

I used to wonder where she had come from, and who her people were; what language her mother spoke; what was her mother tongue. Later I would learn that Jane couldn’t have been born in Africa, since the slave trade to America ended in 1808. But her grandparents could have been Africans, and quite probably left the continent from the Gambia River or just north of Congo, “almost certainly on a British ship,” the historian of the slave trade David Eltis tells me. Only DNA can tell me more. Her tightly wound hair and those high cheekbones and that glassy stare were all of Africa that had been left behind for her great-great-grandchildren to ponder. Where were your people born, Jane Gates, the African? Could we ever bring your people’s culture and history out of the shadows?

It was hard enough in the 1950s to wrap one’s head around the slave experience, outside of shaping signifiers such as “Gone With the Wind” and Disney’s “Song of the South.” But Africa and its Africans? Who could imagine more about Africa than “Tarzan” and “Ramar of the Jungle”? Except for the relatively few African-Americans who saw through such racist fictions of Africa, drawn upon to devalue their humanity and justify their relegation to second-class citizenship — people such as Garvey, Henry Highland Garnet, Martin R. Delany, W.E.B. Du Bois (who would die a citizen of Ghana), Langston Hughes and Maya Angelou — far too many of us felt that “Africa” was something of an embarrassment. Richard Wright, the great novelist, published a book titled “Black Power” in 1954 about feeling that way.

That began to change for me sometime around 1960, the year that 17 European colonies became independent African countries, following Sudan in 1956 and Ghana in 1957. I was in the fifth grade by the time these countries were born, with arresting names such as Togo, Madagascar and Somalia, and more familiar ones such as Senegal, Nigeria, Gabon and the Congo. Our geography teacher, Mr. McHenry (our only male teacher), hung a map of the world listing recent events in front of the blackboard every Monday. Our task was to master the details of nine or 10 newsworthy events. Africa was all over this map.

That’s how my love affair with Africa began. I memorized the names of the new countries and the names of their leaders — Patrice Lumumba and Moïse Tshombe, Léopold Senghor and Kwame Nkrumah — and exotic-sounding city names: Dar es Salaam and Mogadishu, Dakar and Kinshasa. Then we read an incredible story, perhaps from Reader’s Digest, about a boy who walked across the Equator. I wanted to cross the Equator, too.

So many of the students of my generation at Yale were introduced to African art and culture through a wildly popular course taught by the eminent art historian, Robert Farris Thompson. Studying these things within the womb of the black cultural nationalism of the late ’60s and early ’70s made the appeal — the lure — of Africa irresistible, as Du Bois might say. So, when opportunity knocked, I answered the door.

The door that opened Africa to me was an exceptionally imaginative gap-year program at Yale. It sent 12 students to work (not study) in a developing country between sophomore and junior years. I ended up working in an Anglican mission hospital in a village called Kilimatinde, in the middle of Tanzania, about 340 miles from Dar es Salaam, with a population of about 6,000 today — far smaller than when I arrived there in August 1970. Several months later, I would hitchhike across the Equator with a recent Harvard graduate named Lawrence Biddle Weeks, ending up in Kinshasa before flying to Lagos, then on to Accra, to visit Du Bois’s grave. Two years later, I would find myself in the Cambridge University classroom of the great Nigerian playwright Wole Soyinka, slowly but inevitably falling in love with the idea that I might become a professor of African studies.

African history is replete with riveting stories that refute centuries of stereotypes about black people and that show our shared humanity: Our common ancestor, Mitochondrial Eve, 200,000 years ago; the out-migration of our anatomically modern Homo sapien great-grandparents 50,000 to 80,000 years ago; the still-magical Nile River kingdom of Egypt and its rival Kush around 3,000 B.C.; and Emperor Menelik II’s heroic stand on the plains of Adwa on March 1, 1896, when, blessed by a replica of the ark of the covenant, he soundly defeated an Italian army.

African history is an encounter with “kings and queens and bishops, too,” as the song says, including a black queen of Meroe who defeated the Romans in 24 B.C., then confiscated and buried a statue of Augustus Caesar before her throne so that her subjects could gleefully walk on his head. The third nation in the world to convert to Christianity was Ethiopia, in A.D. 350. How many of us know that the Sahara was a trading highway or that the ruler of Great Zimbabwe, in the late Middle Ages, dined off porcelain plates made in China?

Africa — contrary to myths of isolation and stagnation — has been embedded in the world and the world embedded in Africa. There was nothing empty or blank about it except the willful forgetting by the Western world, after the onset of the slave trade, of Africa’s long and fascinating history.

Though not very likely, I like to think that Jane Gates’s grandmother would have passed down even one of these many riveting stories, and eventually it would have been passed down to me. Our challenge today is to ensure that more and more stories like these become a central part of the school curriculum, as well as the stuff of documentaries and the mythologies of Hollywood, so that they will never be lost again.