Hot Spots in Africa and That Question Again: Conflict Management Failure or Endemic Catastrophe?

A cartoonist’s representation of great power contestation in Central African Republic

The current line-up of the African leaders

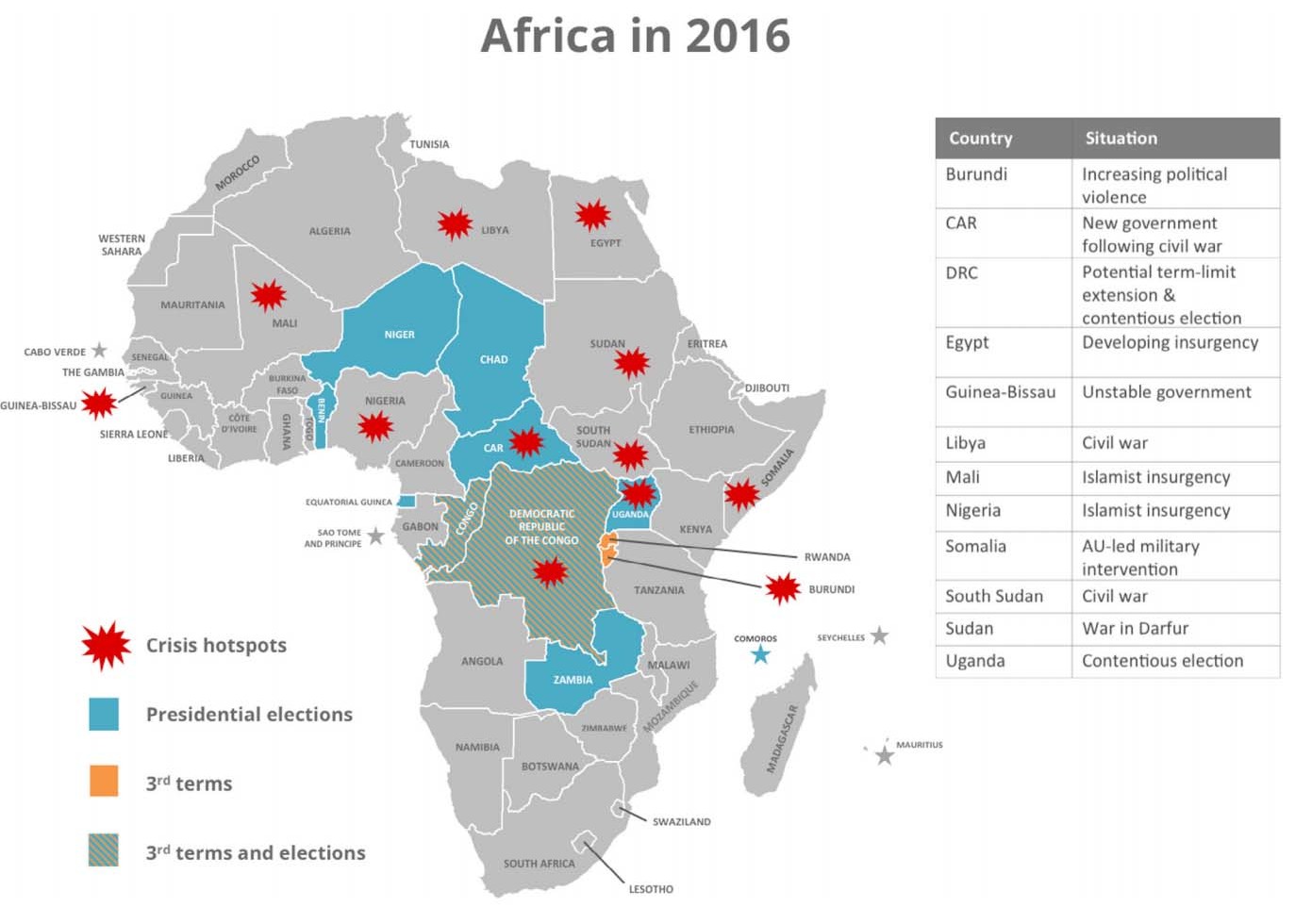

At the 2014 US-Africa Leaders Summit, African leaders disagreed openly before journalists on the question of how stressed the continent was. There were those who held the view that the continent had calmed down and they located the evidence by pointing at only two hot spots or flashpoints as the most worrying then. For Mr Jakaya Kikwete, the then president of Tanzania, these were Somalia and South Sudan. But Moncef Marzouki, Mr Kikwete’s counterpart from Tunisia objected to Mr. Kikwete’s analysis, saying Sudan and northern Mali were as troubling as hell. There isn’t such a huge gap between August 2014 when the summit took place and December 2016 where we are and it seems those who were worried about the continent’s conflict profile were more sensitive.

Certainly, the continent is not its old self as in the immediate post Cold War when conflict management experts were forced to ask the question as to what Africa was suffering from. One particular academic paper found a very memorable title for the puzzle in: “The Persistence of Conflicts in Africa: Management Failure or Endemic Catastrophe?” In 1994 when this paper was published, it was the question to pose and this was a winning title in the light of ethnic violence, genocide, transition fiascos and incomplete national liberation wars. Over the years, there has been a decline. Recent developments, however, force in the question as to whether there has, indeed, been a decline. Many would say that there might have been a decline in number but not in intensity. And they would have places to point to, not the least what must be the three hottest African conflicts at the moment: South Sudan which is, by consensus, heading for genocide if the world doesn’t step in; the DRC which has hardly ever known peace since its independence and the otherwise small but beautiful country called The Gambia.

First is the South Sudan. The current representation of South Sudan is predominantly that of total breakdown of law and order and the survival of the fittest that characterises such a ‘state of nature’. The humanitarian crisis has reached the fullest, with population fleeing to nowhere in total confusion. Official and unofficial sources have concluded it is a case of a looming genocide, similar to Rwanda in 1994, unfortunately. The UN has clear provisions on what to do to prevent genocide. But the politics of power could overwrite all such clear provisions. In 1994, it did and the question is whether history will repeat itself in 2016/7, this time in South Sudan.

The two other cases are cases of transition fiascos: the incumbents won’t go away after exhausting their tenure limits. For most observers, the more interesting of the two would be President Yahya Jammeh of The Gambia. He has been on the ‘throne’ for 22 solid years, with little to show for it, with very poor rating in human rights. He presided over his own defeat in a presidential election whose outcome he initially endorsed by congratulating the winner before turning full circle to say he no longer accepted the outcome. The fear is that he has the capacity to throw the country into turmoil because, having been in power, he has both symbolic and material power resources to trigger instability. And to sustain it!

Joseph Kabila of the Democratic Republic of Congo is a smarter sit tight player. Number one, he has not conducted any elections and there is no result on the basis of which anyone could say he must yield to. Number two, it is not too clear if his exit will intensify instability or reduce it. He has been there since 2001 and has exhausted the two terms he is entitled to. The two complications in this case are, one, the country is at war and some people argue that certain things needed to be done before the transition takes place. The second is the joke that the real problem he has is the red carpet rolled out for him by Beijing. What is being suggested is that concessions granted to China in terms of access to DRC’s natural resources is what has fuelled the agitation for him to go, regardless of the imperative for some consensus preceding the election originally scheduled for last November. Interestingly, although this proves nothing in itself, Joseph Kabila was one of those that John Kerry, the out-going US Secretary of State met with at the US-Africa Leaders Summit in Washington in 2014. And The New York Times reported that when Mr. Kerry went to the DRC earlier that year, he told Kabila to follow the constitutionally stipulated term limit and take his exit.

The persistence of conflicts in Africa could be a complicated phenomenon to make sense of. There are ethnic complications, the ideological politics and the game great powers play with and on the continent. The DRC might be cited as the most concrete case study in Battleground Africa. In this sense, the power factor in the persistence of conflict in Africa is perhaps the value Professor Eghosa Osaghae, the perceptive author of the paper in question, might wish to add to this work seeing as timeless the poser is becoming.