By Adagbo ONOJA

Muhammadu Sanusi II, the vocal Emir of Kano argues that unless the Federal Government privileges foreign investment, it is wasting everybody’s time. It cannot privilege foreign investment if it maintains an unruly exchange rate regime that has already ruined the credibility of any such attempt. Yet, the exchange rate is at the core of foreign investment now needed to grow the economy in the wake of the evaporation of high commodity prices which provoked the ‘Africa rising’ narrative. Without that splash, then consumption, exports and investments are the strategies of growth left. Since both public and private consumption rely on increasing revenues and exports on price rise of oil in the Nigerian case, (which is out of it now), it leaves Nigeria with only investment. But, by investment, he meant foreign investment since the local capitalists are what former president Obasanjo calls ‘baby capitalists’, people who still have to be spoon fed to survive. So, for the emir whose risk analysis is still active, no investors would come around if the certainty of profit is not guaranteed by way of the value of the naira in relation to the hard currencies.

Meanwhile, by his assessment, there are alarm bells ringing such as the danger of collapse of the power sector where he claimed that the reforms have stalled. His medium term strategy is where the government anchors on creating conditions for local manufacturing capacity, not FX swaps with China, for example. These are just two of the many segmented alternatives he professes, citing Kenya as an African success story in doing so, Kenya which is 15% of the size of the Nigerian economy. If we do not emulate Kenya, then we should be prepared to follow the example of Egypt, he asserts, a reference to Egypt’s eventual embrace of coming fully and formally under the IMF.

Shorn of the jargony, what the emir wants is Nigeria to successfully supervise the self-imposition of market forces, manage the devaluation of the Naira, the liberalization of foreign exchange, throwing away any element of fuel subsidy, raise capital from outside and do just about any other things that would attract (foreign) investment. It is, by now, the most popular offensive to react to any such discourse of the economy as the emir has done by saying that every theory is for someone and for some purpose. In other words, his references, invocations, comparisons, appeals to the authorities he cited and so on and so forth all totalize to the purposive defense of a world view and an interest which could be class or group or self interest. What that means is that critics would not accept that there is anything called (foreign) investment in and of itself that is not linked to class, group or personal interest.

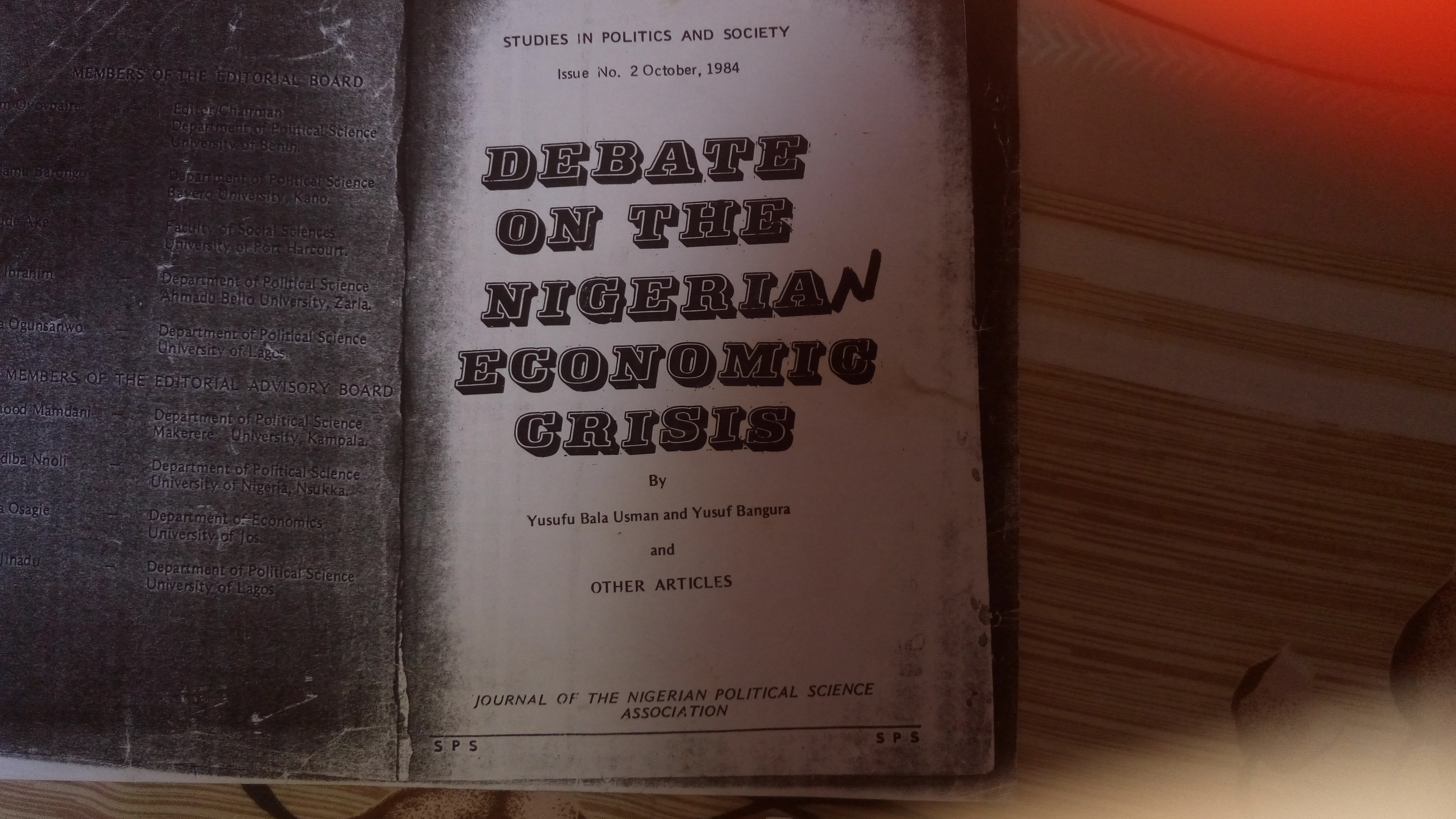

By that as it may, what is even more interesting is how the Nigerian economy has been a subject of this kind of debate. That is to say that the wrestling going on now between the Emir of Kano on the one hand and the Federal Government and its supporters on the other hand has been a regular feature since Nigeria entered crisis in the early 1980s. And this report argues that one such very sensational, cutting edge and far reaching debate was the one between two academic heavyweights at Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria in 1984. It has been collected in a journal which serves as the cover page of this story.

Dr.Yusuf Bala Usman and Dr Yusuf Bangura were the two academics. Yusuf Bala Usman is late now but Dr Bangura lives, though he left Nigeria since the late 1980s. While Bala Usman was in the History, Bangura was in Political Science.

The debate took place in 1984 when words such as imperialism, class struggle, Socialism and so on were not as strange and distant expressions as they are today and when ‘dissidence’ scholars had not intruded in to dilute Marxism. So, the reader may be warned to expect such concepts in a newspaper reports but they are at liberty to edit and replace imperialism, for instance, with globalisation and so on. A detailed summary of the first shots at each other by the combatants is considered necessary for the sake of those who might be encountering the debate for the first time vis-à-vis relating it to the on-going version between Kano emir and the Federal Government and the question of which side has anything closer to the resolution of the economic crisis. It is important to note that people are already dying and the economic crisis is, therefore, a grave topic.

Dr. Yusuf Bala Usman

Bala Usman took the first shot in the debate in January 1984 at a lecture he delivered at the then University of Ife, now Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife. He called it “Middlemen, Consultants, Contractors and the Solutions to the Current Economic Crisis”. His main argument is that the only sound and permanent way to resolve the economic crisis is to create, build and forge what he called powerful organisations that would enable the ordinary people ensure their livelihood and dignity through control of the organs of the state. In other words, it should be all about recognizing certain key features of the crisis and responding to such features in totality by dismantling what exists in favour of a new and independent national economy in the service of the people. It would serve the people because it would be based on direct labour, nationalization of foreign trade and establishment of co-operatives of producers and consumers, among others. Socialist in orientation corresponding to theory and practice of those days, Bala was sure that there were no alternatives to this because such alternatives would be no more than tinkering with mundane manifestations of the crisis such as hoarding, fraud and embezzlement and ostentatious consumption. The result of that approach, he pointed out, would be where the ordinary people would soon be blamed for failure to be patriotic or disciplined, just as happened shortly after his lecture and even now.

The opening sentence of his lecture is, however, completely applicable to the situation today. He began by saying that the country was suffering from the worst economic crisis in its history and that the 1983 coup had not changed the harshness of that reality. Instructively, the Emir of Kano started his December 2nd, 2016 lecture at the Savannah Centre for Diplomacy, Democracy and Development by asking the question: why is this crisis different from the last one, implying its severity. In 1984, Bala Usman feared that the coup was trying to address certain manifestations such as hoarding and the scarcity of essential commodities but that what he called entrenched domestic and external forces whom he said were responsible for the mess would soon re-assert themselves, producing an outcome in “recriminations, confusion, demoralization, disruption, repression and deepening external manipulation”. So, he assigned to himself the task of going beyond the surface to capture both the appearance and the essence of the crisis. And what did he find? He found agricultural decline, factory closures and energy disaster in which, for instance, the Federal and state governments were owing NEPA N500m but wouldn’t pay. And all these were happening at a time “625 of the firms which collected import licenses and used them at least to take out foreign exchange, refused to pay import duties of up to N1b”.

Bringing his critical gaze on the dominant narrative of global recession and oil glut as the explanation for the crisis, Bala called it a smokescreen, pointing out how even President Shagari had questioned that explanation by saying in 1982 that high rates of importation and foreign exchange disbursement had done greater damage than oil glut. He further questioned the oil glut explanation by contrasting it to the corruption and mismanagement of resources thesis favoured by General Buhari while addressing the diplomatic corps and the World Press on January 4th and January 5th, 1984 respectively.

Next, he went on to show how the oil glut thesis did not apply to productivity or to average monthly energy production in ten countries, these being the United States, United Kingdom, France, West Germany, Canada and the USSR. Others were East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and Hungary. In the case of China, it was an all round spectacularity, from agriculture to energy to industrialisation and so on.

His conclusion is that the explanation for the Nigerian economic crisis had to be looked for elsewhere because the oil glut one wasn’t it. The explanation, for him, is the way the structure and processes of the Nigerian economy and society had, in his words, been shaped and moulded to serve the capitalist economies of Western Europe, North America and Japan and there was nothing universal or global, natural or immutable about oil glut. In explicating, he privileged what he called the parasitical but influential role of consultants in the Nigerian economy, bringing out the rise in figures of payments abroad for management and technical consultancy in the past few years and naming names. So, he came up with conceptualizing the political order as contractocracy – government of contractors, by contractors and for contractors. Politics, he said, had been reduced to a fight between and among greedy tycoons, “each backed by their foreign masters, each waving some tribal or sectional banner to confuse and divide our people”. Typically Bala, he sank his teeth into official reports to expose “the magnitude of the roles of contractors (and, of course, of consultants who define and rationalize designs and terms of contract)”.

He categorized the middlemen. There were the importers, exporters, currency arrangees, oil middlemen and commission agents, all of whom he connected to profiteering and repatriation, citing the case of the cement armada which resulted when, according to his account, Western cement monopolies and their local agents resisting importation of cement at cheaper costs from the USSR blocked the import by getting a government department to order 16m metric tons of cement. Nigeria lost N1b to the armada. This is not to mention his statistics of company profits even in an economy that was depressed. It was this causation that he sought a collective response in participatory democracy or people’s power of a type in favour of a national economy.

Yusuf Bangura

Dr. Bangura delivered his paper in April 1984 at a conference of the Nigerian Political Science Association which was still a vibrant player in the knowledge/power interface in Nigeria before its current ‘silence’. He called his paper “Overcoming Some Basic Misconceptions of the Nigerian Economic Crisis”. Bangura did not set out to castigate Bala Usman. In fact, up to a point, they were in agreement, particularly regarding the contradictions between the national and the international economy within the context of capitalism. He too attacked the oil glut argument as an explanation of the crisis, pointing out how the glut itself and the associated depression have to be analysed within the totality of capitalist relations which produced those features.

The question Bangura asked is the question of how best the crisis could be understood between competing explanatory models as neoclassical economic theory and its internal critique by the monetarists as one, the Marxist framework as another and what he called the Third Option explanations. Trouble started when he classified Bala’s argument in the Third Option framework which carries with it the suggestion that Bala’s grip of theory was weak. That is weak in the sense that it did not have the rigors of the neoclassical/Keynesian claims nor does it satisfy the Marxist canons of contradictions, crisis and class struggle.

Neoclassical economists, led by Maynard Keynes argued in response to the post World War depression or recession, if you like, that the problem could only be solved by government intervention in the economy with more money and the creation of employment. Government intervention in the economy is an attack on the classical liberal theory of invisible hands guiding demand and supply to equilibrate. It is the Keynesian argument that became what is known as the Developmental State in the ‘Third World’ till today. In Nigeria, some scholars would say that the case for the Developmental State was settled in 1973 during that year’s conference of the Nigerian Economic Society where all the economists, radical and bourgeois, unanimously accepted its strategic inevitability. Many would say that nothing has changed to change the 1973 consensus and that the Developmental State is even more urgent now. But the monetarists have since become so powerful as a force against Developmental statism, arguing against more money in the economy on the ground that it is anti-investment.

In the context of the crisis, Bangura’s argument is that most Nigerian economists have acted as a transmission belt for the diffusion of monetarist ideas, they being part of the harbingers of the worldwide recession/oil glut analogy; the loud lamentation about low savings, low productivity of workers, high wages and the idea of excessive government expenditure. He meant that each time we hear these sorts of argument, it is a monetarists wailing and railing against the system and they are no neutral actors in the arena. We are told to take such a wailer or wailers as standing for the investor class and their interests. Bangura attacks the explanatory model and uses the same words as Bala Usman to allege “smokescreen to cover up actual agencies and structures involved in creating crisis”.

Applying these frameworks to the Nigerian economy, Bangura arrived at the conclusion that the Nigerian economy is an integral part of the capitalist world economy, notwithstanding the small size of the capitalist sector co-existing with its pre-capitalist Other. As such, it manifests contradictions central to dependent capitalism such as the situation whereby surpluses, (profits) realized in Nigeria are taken away to advanced Western countries rather than re-invested in Nigeria. He quotes Buhari’s statement in 1984 to the effect that every N1 given to Nigerian and transnational companies, 68 kobo found its way out of the country. So, he says that “despite the huge amounts of profit generated in all sectors of the Nigerian economy, such as the oil, banking, manufacturing and the state, the level of development remains retarded. Again, he stood the same grounds as Bala.

That was until he went on to add that there were those who were looking at the crisis neither from the neoclassical or its monetarist critique nor from the Marxist analysis of the contradictions of global capitalism but who, instead, isolates mismanagement and corruption. And that such analysts cite the resulting proliferation of middlemen, consultants and contractors as where the problem could be located. The heart of that analysis is where Bangura says that “sections of both the left and the right share parts of these positions, with the left concentration on what has been called ‘contractocracy’ and the right on the problem of mismanagement and indiscipline”. Other than Socialist planning, there is no way the Nigerian economy can be managed to avoid mismanagement, Bangura asserts and went on to say those who expected better management could not be serious. So also does he not think that corruption and looting of public treasury could explain the crisis although admitting they could aggravate it. As for contractocracy, he disagrees that this could be understood outside of the imperialist framework without such amounting to separating the trees from the forest. Otherwise, he argues, there are more contractors in the Western economies than anywhere else. In all cases, contractors and contractocracy could not be understood outside of the general dynamics of the world capitalist economy.

This is where the summaries will stop as the reaction to the theoretical classification of contractocracy in the Third Option framework took over the debate, triggering acrimonious exchanges over two or more academic essays replying each other. For academics, theory matters but theory must keep being refined. Some people would, therefore, say that the spacing of contractocracy could only have triggered the degeneration of the debate were it not for the subsisting razor sharp tendency hostilities already existing in Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria’s battleground called the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, aka FASS.

But the two all took a systemic view of the crisis, harping on the crisis as an outcome of the location of the Nigerian economy in the global capitalist order. The difference is the weight Bala Usman placed on the role of a specific set of actors – the middlemen. That made sense for the purpose of concretely specifying how the system works.

The pair of the Emir of Kano and the Federal Government in the current debate in 2016 differs remarkably from the 1984 set in the sense that the 1984 debaters all disagreed and dealt with the monetarist critique of neoclassical economics. In the 2016 crisis, the president appears indisposed to devaluation and certain other features of the neoliberal package but he is not standing up for the developmental state either. He makes pronouncements that suggest such a preference but neither he nor any other person in government says anything fundamental against full blown neoliberalism. In fact, the government is implementing it.

The Emir of Kano, on the other hand, promotes the case for a self supervised neoliberal approach, putting too much weight on the liberalization of the economy to attract foreign investment. He is not too bothered about questions why the investments have not come since 1986 when the neoliberal package was fully adopted by the government. But that the investors are a problem for the economy is a point a key actor such as former president Obasanjo has been consistent about. What Obasanjo said about foreign investors in 1978 is also what he had to say in 2002. As military Head of State in 1978, he said:

“…experience has shown that most of the so-called foreign investors come in with little or nothing in finances; they raise internal loans from the savings of ordinary Nigerians and within months, they are devising all means (of) repatriating huge sums out of Nigeria in the form of dividends, profits, management fees, loaded invoices, etc. To illustrate the point I am making, last year, I ordered a research to be carried out on investments actually brought into Nigeria between 1960 and 1978. The result was revealing. A bank which came to West Africa with N209, 000 capital at the beginning of this century and without another kobo brought in as investment since then, had an equity capital of N32, 000, 000 and with about the same amount having been repatriated since its establishment”.

As a civilian president in 2002, Obasanjo also spoke of how he travelled round the world in search of foreign investment but only got good words that translated to nothing in foreign investment terms. If the problem with the Buhari regime is mismanagement of the exchange regime, was that also the problem under Obasanjo between 1999 and 2007 and under Jonathan between 2010 and 2015? Meanwhile, the Emir admits that the reform in the power sector has stalled and that the danger of total darkness is real and he wants the government to intervene there. Is this how Nigeria will be tumbling about, permanently unable to ground the Nigerian economy in a more pragmatic but transformative discourse of national destiny? </br>