For more than half a century African universities have been fully invested in denouncing colonisation and exalting decolonisation. In a piece, ‘From dumb decolonisation to smart internationalisation’, published on this platform a while back, I argued that this preoccupation with (de)colonisation has eclipsed African universities’ gaze on the tectonic political, economic and technological shifts that have been sweeping the world.

The morass of colonisation has long morphed into a hegemonic behemoth – an intricate web of political, economic, diplomatic and intellectual dominance that has shaped global systems for decades.

This enduring structure has not only dictated the terms of international engagement, but has also reinforced asymmetries in the domain of science, technology and knowledge.

Meanwhile, Africa has remained largely on the margins, often caught up in cycles of lamentation over its long and painful colonial past.

Rather than simply continuing to bemoan this history, the continent must now reckon with its present position and reclaim its agency by reimagining its future, guided by home-grown priorities, values, interests and ambitions – and, equally importantly, leveraging fast-shifting global alliances. It is time for the lamentation to come to an end – and the discourse to shift from decolonisation to dehegemonisation – with universities playing a central role in this shift.

The unravelling of hegemonic alliances

The unravelling of hegemonic alliances

A bewildering landscape of fractured alliances among hegemonic powers has been unravelling over several years, with a particular intensity in recent months.

It is just over 100 days since the new United States administration assumed power and it has been aggressively dismantling the global world order, or whatever is left of it. As a consequence, global alliances now teetering on the brink are faced with unprecedented disarray and anarchy.

The current state of global chaos marked by intensifying geopolitical tensions – economic fragmentation, shifting power dynamics, trade wars, technological disruptions and the erosion of multilateral institutions – offers a paradoxical, yet critical, moment of opportunity for nations that have historically been positioned at the political, economic, and knowledge peripheries.

This phenomenon is likely to give birth to new hegemonic and non-hegemonic alliances with potential for the emergence of multipolar power centres in Asia, Latin America, and potentially in Africa, too.

For these nations, including those in Africa, situated at the margins of global political, economic and knowledge systems, this period of disruption could serve as a critical inflection point. Instead of passively absorbing the ripple effects of these global instabilities, triggered by global hegemons, such nations must strategically harness the moment to reassess, renegotiate, and reformulate their position in the shifting global order.

These countries ought to capitalise on this historic moment to rethink and reformulate their place in the emerging, yet to be settled, global hierarchical configuration. In doing so, African universities can and must play a pivotal role – with a comparable level of anticipation, ambition and aspiration exhibited at the time of independence.

As key institutions of knowledge production, intellectual hubs, centres of dissent and incubators of new ideas and innovation, universities are uniquely positioned to drive this transformation as catalysts for reimagining national and continental futures, by advancing critical discourses that foster dialogue around global development and governance.

Through robust research, informed policy engagement, and the training of competent future leaders, universities can help redefine national and continental agendas that are rooted in local realities laced with global competitiveness.

In so doing, universities can help reshape national and continental narratives and reposition marginalised nations within a more just and multipolar global order. Thus, what may appear as global chaos could, in fact, be harnessed as a moment of renewal and empowerment – if seized with clarity of vision and bold institutional leadership.

This moment of global uncertainty calls for a renewed focus on intellectual sovereignty, resilience and re-awakening – domains in which higher education institutions must take the lead.

Through investment in their research capacity, promoting indigenous knowledge systems, and forming equitable international partnerships, universities can help marginal nations claim greater agency in global discourse on climate, public health, energy, trade, investment, AI, extractive industry and international relations, among many others.

A truly equitable partnership may emerge as extant, yet dysfunctional, modalities of global partnerships are challenged and relegated as a consequence of the changes under way.

South African universities all the way?

Universities in the shifting winds

As the old order crumbles, a new shall inevitably emerge. For Africa to be one of those power centres, its institutions – led by its universities – must take centre stage in shaping its trajectory in the unsure new world order.

In this chaos, which is difficult to forecast, nations must cushion their universities, institutions and other citadels of knowledge to position their nations in charting the way forward.

University consortia, associations and research centres across continents must deliberate on the global issues and re-articulate their roles.

Universities in Africa, through robust global studies programmes, among others, need to help navigate this fast-shifting global phenomenon and endeavour to shape it with renewed vigour.

Institutions in Africa need to work closely with multiple, like-minded national and international actors, including those in the hegemonic capitals, to properly serve their countries’ interests.

From vaccines to climate change, from issues of equity to race, the academic and professional world has increasingly been assaulted by hostile views driven by politics that feeds on anti-intellectual sentiments.

High-powered leaders that deny scientific (such as vaccines) advancements and human-induced natural phenomenon (such as climate change) now have enormous political and economic power to dismantle the modus operandi governing these issues.

Universities in the US are now scaling back on some these issues – and so are their partners elsewhere in the world – including in Africa, where they were being heavily supported through schemes from the US government.

These means that these issues, of profound importance and that have massive consequences for economically less-advanced countries, must be pursued with even more vigour by engaging institutions – including those threatened in the US and beyond.

Roles of stakeholders

Roles of stakeholders

Advancing national and continental interests in the context of shifting global alliances requires a deliberate and systematic engagement among multilateral and continental agencies, governments and their ministries, universities, academic departments, and individual scholars.

When each stakeholder plays its role effectively, guided by shared vision, a sense of ownership, mutual accountability, and strategic and equitable collaboration, a country can respond to global changes and shape them, ensuring that its values, priorities and aspirations are reflected on the international stage.

Government ministries, particularly those responsible for higher education, science and technology, foreign affairs, and finance play a central role in creating an enabling environment for national engagement in global affairs, when deployed in a strategic manner.

They need to involve, proactively and synergistically, funding and resource mobilisation, diplomacy and global positioning. For instance, African governments and institutions must establish and strengthen think tanks and global studies in the universities and research institutes.

Universities, as the intellectual hubs of nations and bridges between national priorities and global developments, need to design and review curricula and programmes proactively and rigorously. They should also sharply focus on ‘smart’ internationalisation to build a global coalition through like-minded partners, joint research and degree programmes, academic exchanges, and collaborative research initiatives.

African universities should also be more vocal, more active and more visible in the global political and development scenes, among others, by sponsoring public policy dialogues, publishing compelling opinion pieces on leading platforms, and encouraging and demanding academics to engage in such exercises.

Academic departments, as the basic operational hubs, should implement the development of targeted and specialised research agendas that focus on global developments and national imperatives through interdisciplinary collaborations and leadership development.

Through local-global integration, universities need to act as active conduits for bringing global ideas into local contexts and vice versa, ensuring that research and teaching remain globally informed and locally grounded.

Individual academics, as the key knowledge producers and brokers who shape both the academic and public discourse of global developments, need to engage more in key global issues through publishing, media engagement and policy advisory roles, bringing national perspectives to global fora.

They need to actively participate in collaborative research with global partners to position national institutions in the international academic arena and engage in both research and public policy to advance national interests vigorously and responsibly.

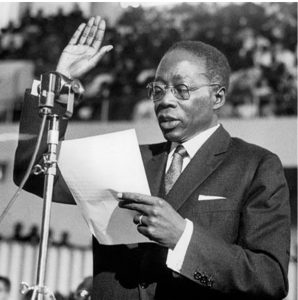

Embodiment of an African perspective, the poet – president, Léopold Sédar Senghor (1906-2001)

Shaking entrenched dependency

Africa’s massive dependence on external, hegemonic, resources for research and knowledge production has been well established. The chronic dependency has continued as governments failed to commit 1% of their GDPs, as prescribed, to research and development.

It remains perplexing that nations investing heavily in education consistently fail to extend comparable support to research, thereby leaving academics and institutions in a state of perpetual dependency on the ever-changing priorities of hegemonic powers.

As global alliances continue to shift and traditional hegemons scale back their commitments to development cooperation, external resources are expected to dwindle. This unfolding reality may serve as a catalyst, or even a necessary provocation, for African nations to finally take full ownership of their long-overlooked responsibility to invest in and sustain their own research and innovation ecosystems.

The shifting global winds, challenging long-standing hegemonic powers and triggering profound systemic changes, could ultimately lead to the emergence of a self-reliant African continent that fully funds its own research and innovation agendas.

This transformation could serve as a powerful antidote to the deeply entrenched dependency that has long gnawed the region’s development trajectory.

Such a shift would not only restore agency and dignity to African knowledge production but also allow the continent to set its own priorities, shape its own narratives, and contribute meaningfully to global discourse on an equal footing. In this lies a truly liberating and sustainable path forward.

Conclusion

While Africa and other so-called developing countries have been stubbornly preoccupied with often stale decolonisation narratives and dialogues, the alliance of hegemonic forces has effectively, and successfully, consolidated self-preservation and self-interest.

Now that a new global reality is unfolding, African countries need to proactively engage, re-calibrating their positions, interests, practices and discourses – in the writing up of a new compact. The role of universities in realising this remains critical.

African universities must, thus, be strategically deployed as instruments of progress and development to harness human, knowledge, material and financial capital, which are key in the pursuit of dehegemonisation, and also for the continent’s ‘benevolent hegemonisation’.

University World News from where this has been extracted introduced the author in the following terms: Damtew Teferra is the founding editor-in-chief of the International Journal of African Higher Education, professor of higher education and founding director and convenor of the International Network for Higher Education in Africa based at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. He facilitates the Continental Education Strategy for Africa – Higher Education Cluster spearheaded by the African Union Commission and coordinated by the Association of African Universities. He may be reached at teferra@ukzn.ac.za or teferra@bc.edu.

*Except the Mudimbe book cover, all the other pictures and graphics were sourced from Afrorama Facebook