The author, also known as ‘Junior Aminu Kano’

By Y. Z. Ya’u

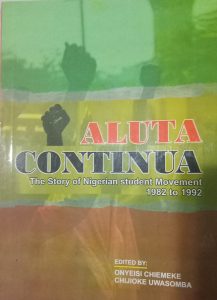

Cde Y. Z Yáu, the Executive Director of the Kano based Centre for Information Technology and Development (CITAD), delivered this review of the book Aluta Continua: The Story of Nigerian Student Movement 1982 to 1992 April 7th, 2025 in Abuja at the public presentation of the book published by Rosa Luxemburg Foundation

There is a certain fascination with the student movement among both prodemocracy campaigners and left-wing activists. This fascination is not without basis. Student activism was a key instigator for the nationalist’s stirrings that coalesced into the anti-colonial struggles. Students associated with the National Youth Movement (NYM) constituted the ranks of both the NCNC and the Zikist Movement. In the immediate post-independence era, it was the massive opposition by students that saved the country from mortgaging its newly acquired independence by signing the Anglo-Nigeria Defence pact. Since then students, whether organizing under NUNS or its successor platform, the NANS, have continued to play critical roles in the country, shaping debates and public opinions, influencing policies, resisting autocracy and contributed in dislodging the military from the political sphere. The last resulted in a long-drawn battle to rid the country of military rule that clothed the country in a terrible authoritarianism garb.

In some left circles, the student movement was seen (certainly not now) as the vanguard of the socialist revolution, displacing the working class, which was seen, implicitly, if not explicitly, as too backward to lead the struggle for the revolution. Indeed, in the introduction to the book under review, the editor of the book under review made the point that student intervention in the country was revolutionary. To quote him, “It is the dominant contention that the struggle of this period was revolutionary in nature. This is because the struggles of this period posed the question; Anti-Imperialism and Neo-Colonial Capitalist Structure of the Nigerian State”.

In spite of the fascination with the movement, the student movement is not well documented. There are just a couple of serious studies. This is thus a welcome addition, especially in the time that mercenaries have taken over the student movement and the erstwhile fascination it held is now replaced by a contemptuous cynicism. It is interesting that this book could be written at all. The editors spent considerable volume of words in the introduction, explaining the many disappointments they had endured to fret contributions out of the former student activists, with many of the comrades penciled out to make contribution, opting out of the project. But they were sensitive enough to observe that writing itself was not an easy task. They noted that “writing is a tedious process” and quote Oz who noted that the “writer is a broken” after the writing. But it is not just the “writing frailties” of some of the contributors that made writing of the book difficult. There were other factors at play as well. Activists were no documenters, even when they were good writers. They went about doing their activism, without the time or flair for documentation or reflection, to render their experiences on paper. When the subject of recollection itself was over 20 years past, the memory becomes weak. Yet there is also an additional disincentive which is a carryover of their activism: often during the struggle, people who paid attention to documentation, were regarded with suspicion, either they wanted to promote their personal profile by writing themselves in the movement struggle or worse, they might be security agents (could they be writing to pass intelligence to the state with which to destroy the movement?) who should be delinked from the movement. Perhaps, the comrade find writing as too ineffable, trying to conjure memories that have become elusive.

The book, “Aluta Continua: The Story of Nigerian Student Movement 1982 To 1992” is a collection of contributions by former student activists and edited by jointly Onyeisi Chiemeke, a lawyer and Prof Chijioke Uwasomba, both of them former student activists. organized in four parts, excluding the introduction. It provides the reader with a rich compass into the dynamics of student movement and an important glimpse of how students organized and protected and promoted their collective interests as well as how they linked up their campus struggles with the wider efforts aimed at transforming Nigeria into a better and just country. The period between 1982 and 1992 covered by the book was both intense and interesting, full of stories of successes and disappointing tales of decay and eventual collapse. It is a rich trove, not just full of heroic encounters but also lessons that can serve to direct efforts at rebuilding the movement. It is for this reason that we must gladly welcome the arrival of this important book. Living in those tumultuous years, there was this exhilarating feeling that we were witnessing a revolution in the making.

While this was not a holistic study of the movement, it gives us important snapshots of the way the struggles of the movement were organized and prosecuted. What emerges from reading the book is a clear picture of well-structured movement that was invisible to the outsider. In this, we see how they acted in practice. For national issues, the platform was NANS with the Patriotic Youth Movement of Nigeria (PYMN) as the masquerade behind the scenes. The PYMN constituted of a coalition of left-wing student organizations from different institutions. Ideologically committed to socialist transformation of Nigeria, they saw their role as beyond campus struggle. They considered themselves as part of the vanguard for the Nigerian socialist revolution and therefore networked with other movements such as the labour movement in the country and other left-wing parties or organizations, both within and outside the campuses.

For local struggles, the local student unions led with local campus organizations which were affiliates of the PYMN working behind the scenes. Local organizations contested and often won local union elections. At national level, generally the PYMN did slates, allocating positions to its different branches. Key positions were assigned to campuses where the movement was either strong or in control of the student union. It is to the credit of the PYMN that in spite of being in a minority of campuses, it was able to dominate the leadership of NANS until the mid-1990s. In addition to contesting local union elections, PYMN campus affiliates were responsible for mobilizing students around various issues as we have seen in the book, leafleteering, addressing rallies, shaping students’ attitude and responses to local, national and international matters, mobilizing students for protests, etc. Not surprising, they usually paid heavily as schools authorities descended on them with sledge hammer, even when their operations were clandestine and not generally too visible.

Part 1 of the book is a single chapter, dealing with the transition from NUNS to NANS. There is a gap in the narrative here as there is no background of what necessitated the transition from NUNS to NANS, what challenges the activists faced in trying to assert their rights to freedom of association and how they eventually overcome the challenges and established NANS. It would have been very useful to detail that historic convention at which the first NANS leadership was elected. The explanation of the expulsion of Tanimu, the first NANS President needs more context than just he was thrown out by the NPN (the National Party of Nigeria, the ruling party in the 2nd Republic). There was a local protest in BUK over both quality of food and the decision of the university to unilaterally erect a well around Nana Hall, the female hotel. Until 1980, female students used to occupy M block while final year male students were housed at the old block which came to be known as Nana Hall. As a male hotel, it was not walled, however once the female students were moved into it, the university decided to wall it. This was opposed by both male and female students of the university.

Part 1 of the book is a single chapter, dealing with the transition from NUNS to NANS. There is a gap in the narrative here as there is no background of what necessitated the transition from NUNS to NANS, what challenges the activists faced in trying to assert their rights to freedom of association and how they eventually overcome the challenges and established NANS. It would have been very useful to detail that historic convention at which the first NANS leadership was elected. The explanation of the expulsion of Tanimu, the first NANS President needs more context than just he was thrown out by the NPN (the National Party of Nigeria, the ruling party in the 2nd Republic). There was a local protest in BUK over both quality of food and the decision of the university to unilaterally erect a well around Nana Hall, the female hotel. Until 1980, female students used to occupy M block while final year male students were housed at the old block which came to be known as Nana Hall. As a male hotel, it was not walled, however once the female students were moved into it, the university decided to wall it. This was opposed by both male and female students of the university.

Following the inauguration of the newly elected student union leadership with Taminu Kurfi as President of Union, the night after the event, in a feminist awakening, a protest broke first at the female hotel that led to the newly erected wall being demolished. From there, the protesters moved to the VC’s lodge who had escaped. It was the result of this protest that Tanimu, along with the key female activists such as Ladi Isah who was the Vice President of the Union and Comrade Nancy, an activist from the Faculty of Science, was expelled. Of course, Tanimu came into the movement from the PRP tradition and once they were expelled, the PRP government of Balarabe Musa of Kaduna State came to his assistance by sending him abroad to complete his studies.

Part 2 is the main core of the book. Here there are 11 chapters, each a reflection by a cadre from the respective universities. In the words of the editor, these are “focused on recollection of former students who were cadres of the movements of campuses that were considered in this work”. The eleven universities covered are Ondo State University; Bayero University, Kano; University of Benin; University of Calabar; Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria and University of Jos. The rest are University of Port Harcourt; University of Lagos; University of Ilorin; Obafemi Awolowo University and University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Each of these gives a narrative on how the struggle was handled by the local affiliates of the PYMN, the battles they fought and the consequences as well as how local issues of struggle related to national issues. As the editors noted, this was not about the local student union but “how student unions were developed and were run by young cadres belonging to left wing groups in the Nigerian tertiary institutions during the period under consideration”.

The chapters are of uneven length and quality. However, whatever shortcomings they may have, they weave a good narrative around the PYMN as the core of the student movement. All national struggles were coordinated by the PYMN. Local struggles were left to the coordination of the local campus organizations with advice and solidarity from the PYMN. There are two contributions in interview format in the collection.

No criteria for the selection was given and it could just be mere convenience of the available ex- cadres to reflect on their own experiences but even in that, a certain logic could appear obvious. First, with the exception of Ondo State University, the list consists of first and second generation universities. In this, two seem to be curiously missing: University of Sokoto or Usman Dan Fodio University (now) and University of Maiduguri. A further look will reveal that each of these universities, with the same exception of Ondo State University, had held the secretariat of NANS at least once over the period. For instance, ABU had produced the president in the persons of Hilkia Bubajoda and Salihu Lukman, BUK had Taminu Kurfi and Naseer Kura while UNIJOS produced Chris Abashi, Abdul Mohmmed and Comfort Idika. Again, only Ondo State University was an odd one at the third level in that all the rest were federal universities.

In spite of all, it is hard not to notice a certain hierarchy of the student population. Leaderships at the level of NANS inevitably went to university students. This was in spite of the fact that universities were a minority in the combined total number of higher education institutes from which NANS derived its membership. The PYMN in its slating usually allocated positions to campuses with affiliate organizations. Since there were hardly any left-wing organization in Polytechnics and colleges of education, they were inevitably bypassed and given such positions as director of Sports or some other nondescript positions.

While not part of the remit of the book, it would be interesting to ask why was it not possible for the radical campus organizing to spread to colleges of education and Polytechnics? Could it be because these institutions, especially the Polytechnics, did not teach social sciences which provided exposure to Marxist ideas and other left-wing readings for university students? But a number of the cadres from the university based left wing organizations were science students. Could it because these institutions, especially the colleges of education were a transitory stage for people going further to university? A few student activists actually started their activism pre-university. Segun Okeowo for instance, was the President Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo, Student Union, before graduating and moving to University of Lagos where he became the student union President and later the President of NUNS. Similarly, Bamidele Aturu started in the same college and blossomed as an activist when he was admitted to read law at Ife. There were others such as Abiodun Aremu who started at Kwara Polytechnic. Although there wasn’t a formal organization at CAS Zaria, Salihu Lukman and others in his cohorts were already benefiting from the activities of the MPN from ABU which prepared them for more ideological engagement with the student movement. Another possible explanation is that in those institutions there was/is low awareness about academic freedom, institutional autonomy and studentship and certainly not much efforts was put in these institutions to protect and ensure their flourishing.

Whatever the case was, this book also carries the imprimatur of that subconsciousness. Whether deliberate or otherwise, all the chapters were about universities, not one was devoted to non-university types of institutions. Yet a number of them such as Auchi Poly, Yaba Tech, Kaduna Poly, Kwara Tech etc, played very significant roles in protests. Could it be that no cadres from these institutions could be found to offer their reflections? Or were their struggles of second-class substance, not worthy of preservation?

Some former NANS activists at the book presentation

Part 3 consists of two chapters, one on Women in The Nigerian Student Movement and the other entitled “Student Cadres and Lawyers of Merci” contributed by Onyeisi Chiemeke. The chapter on women by Hauwa Mustapha sought to examine how women were part of the movement and its struggles. It makes three important points. One was that the impact of the structural adjustment programme on students and their response to it that led to the brutalization of students transformed many females from passivity to taking active role in the struggle. The second which in sequence should really have been the first was that the founding of Women in Nigeria (WIN), the foremost feminist organization, led to the spread of feminist ideas and thought among students, especially female students. This also resulted in female students coming into contact with other progressive associations such as the MPN, YUSSAN, etc. Hauwa notes an important tension: while virtually all the male student members of WIN were Marxists, the majority of the female students remained feminists, even as the central credo of WIN was Marxist, with its double oppression thesis. At first this did not appear to be a major problem, as most of the advanced cadres considered WIN membership for female students as a starting point from which they could become Marxists. However, and this was not part of the remit of her chapter, the tension, became unmanageable at the national level of WIN when female feminists were fitted against Male Marxists, resulting in the collapse of the organization.

Perhaps, it would have been interesting for Hauwa to have probed the gender and feminist credentials of the student movement: was it deliberately committed to gender emancipation or was it just a tool for mobilization? Moreover, what was the gender politics of the movement? How did it handle women participation and representation? Did married women had any role in the movement, considering the long night hours meetings that were the hallmark of the movement?

In a way, the book itself could not rise above its own context. Out of 16 chapters only one was by a female cadre. Not a single female cadre was considered worthy to write the reflection on her campus. As a token, the female was considered to write about women issues, not about her campus. It will seem to, either unconsciously or otherwise, reflect the gender thinking around the movement. Hauwa herself, the only female contributor to the book here made a reference to how she was “directed” to step down as candidate for the position of student union President in ABU for a male counterpart by a male dominated Marxist core and told to contest for the position of a treasurer” and generally remarking that “women were easily mobilized to join protests and to campaign for Student union candidate, however, women were often ‘given’ the position of treasurer, ex-officio, welfare and assistant secretaries” rather than substantive leadership positions of presidents and secretary generals. Throughout the period no woman became President of NANS and by the time Comfort Idika made it in 1994, the movement was already in tatters and outside the period of coverage of this book.

The second chapter relates to how victimized students found critical support in friendly legal chambers who took their cases to court on pro bono basis. These chambers were few in comparison to the totality of legal firms in the country and they stood iconic in student imagination. They were led by Alao Aka, Gani and Femi Falana. This was very important because being expelled could be traumatic to both the students and their parents: while the parents could be grieving the money spent already in school fees and maintenance and possibility of loss of studentship, both the parents and their wards would find it difficult to bear the cost of legal fees for them to contest the victimization. This support in free legal representation therefore became an important leg of the movement, cementing relation between progressive students and their counter parts in the legal profession. Some of these students themselves could graduate and continue the tradition of providing the same services they had benefited from. For example, Bamidele Aturu whose NYSC certificate was withheld following his graduation from Adeyemi College of Education, where he majored in Physics, he set up chambers after reading law at Ife which came to handle many student cases. Ogaga and Big Sam were also beneficiaries who went on to set up practices that supported student causes. But this could go to play an important role in the founding of the early human rights organizations namely CLO and CDHR. By 1986, many students were detained, some expelled following the anti-sap protests. The number led to new actors who rather than allow their chambers directly handle these cases set up an organization to provide legal services for human rights abuses, including seeking the release of student activists and contesting their victimization in courts. These organizations could play key role in the pro-democracy protest of the late 1990s but as seen in the conclusion of this book, they are also implicated in the collapse of the movement.

But the chapter also bears the print marker of its contributor who himself is a lawyer. Perhaps, if he were not a lawyer, he could probably have written a different chapter on a different issue that related to supporting the student movement. For instance, a trade unionist could have written a chapter on how the labour movement, and especially the NLC became a refuge house for the students and like the legal profession, a number of the students would upon graduation, joined and worked for the NLC and other trade unions as staff. Example include Salisu Nuhu, John Odah, Chom Bagu, Chris Uyot, Salihu Lukman, Ene Obi and Hauwa Mustapha. Similarly, an academic would have written about how progressive academics, individually or collectively, at the level of ASUU provided support for the movement. For instance, it needs to be told how Prof Jibrin Ibrahim travelled to Port Harcourt from Zaria to get Prof Claude Ake to admit Issa Aremu who was expelled at ABU. Others who benefited from such support were for instance, Chom Bagu who ended up at UNIJOS after being thrown out of ABU while Bala Mohammed could join the Department of Mass Communication at University of Lagos after his expulsion from ABU. In the same vain, a progressive politician of the left would have written on how they intervened to ensure that victimized students continue with their studies. Taminu Yakubu Kurfi is one of those who, following his expulsion from BUK, was sponsored by the Balarabe Musa Government to continue his studies outside the country.

The last part of the book is one chapter (chapter 16) entitled “Aluta Continua: Picking the Snails” written by Onyeisi Chiemeke and starts with an interesting analogy of picking snails. Snails are slow moving and have no protection beyond their shells. So, they can easily be picked up by their prose targeting them. In this analogy, the snails were the student activists, preyed upon by the state. Soon the state started to pick the activists, some out of their own carelessness, some out of strategic mistakes and more out of increasing blunders and breakdown of organizational discipline in a movement that was showing signs of cracks from all directions in a context of a more intense onslaught on it by the state. It signposted the degeneration and the eventual collapse of the movement and the loss of control of NANS by the PYMN. By 1995, the PYMN candidate for the president had lost to a coalition of what in the book is called cultists with a faction of the left that was bitterly opposed to the PMYN. Typical story of the Nigerian left sectarianism, it was easier to work with the ruling class faction than to struggle together with different tendencies of the left.

From L-R are the two panelists on the book at the presentation

The chapter concludes with a discussion of the myriad of factors deemed implicated in the collapse of both the PYMN and NANS and this has been fairly well documented in many publications and I will not go into them. Just to note one which has received least attention: it is the impact of Pentecostal Christianity (and I dare say also of Islamic Fundamentalisms). While the allure of human rights activism was visible and easier to observe, the insidious impact of religious fundamentalism on the cadres is less visible but equally important as it sow ideological doubts, displaced organizational discipline and commitment to social struggle was replaced with a struggle for Heaven. The rest is now history.

One of the attractions of this book is that it was contributed by people who were active in the making of that history of the many battles that students fought in the country. When actors become the historians of their encounters, it must reveal something fundamental. Unlike the 3rd person narrative, of observer-documenters, who write with a detachment, and having no access to the minds of the actors, the activist-documenter has the advantage of drawing from personal experience, privy to decision making, and on the spot observation, all of which the observer- third person narrative has no access to.

But the first-person narrative is often problematic, both from its self-censorship in what is to be revealed to the public or the self and the propensity to overreach, in providing narratives of events that were more or less forced by circumstances, beyond control of the actor-writer but now being explained in some rational and logical way, that appeared well planned. But unlike the third person narrative, the first-person narrative offers an inner reading that is not accessible and available to the independent observer. In doing this, the writer is forced to reveal things which at the time were considered as secret.

A key expose in this particular case, is the role of the PYMN which is rendered very visible in the various narratives from the campuses. It is seen that the PYMN was the livewire of the movement, framing, coordinating and indeed prosecuting struggles of the students in the country during the period under review. The PYMN was an effective resourceful platform. It was a collection of left-wing or proto-left wing student organizations based on the campuses, each organizing and providing a platform for the activists to engage issues in their campuses while collectively they coordinated as PYMN nationally. The PYMN was invisible to ordinary students, non-registered anywhere, and generally not spoken of.

In the circumstance, the unveiling of the PYMN as is done here in the book could ordinarily be gratis for the state which now has an intimate understanding of the working of the driving force of the student movement. However, things have changed and the movement is all but dead. In this case the knowledge is not of major use for the state. Yet in spite of all, this knowledge is useful for researchers and activists seeking how to rebuild the movement. It will also be useful for future movement activists, who will have to evolve their own code of operations, with the benefit of hindsight of what the past did.

Conclusion

This book is an addition to a tradition of reflection that started with an earlier book on the student movement. It will be followed by others, one of which is hopefully to come out of the conference on memorializing the late Comrade Emma Ezeazu, one of the longest serving presidents of NANS. With this emergence of self-documentation, we have access to the reflections of activists and student leaders. Hopefully this trend will help capture and preserve the rich history of activism in the country for generations to learn from. So far, we have just a handful of these. much more is needed to be written, both from the perspective of campus-based (as in this book) but also on broader dimensions of the struggles of student movement in its drive to push for the transformation of the country.

I come from an area where we have no masquerades, what we have are called dodos, very close to the masquerades in the Southern part of Nigeria. They are used to bring recalcitrant youth and children to order. However, when the dodo is disrobed of its costumes, it loses its power. The disrobing reveals a frail member of the community who in costumes appropriates the powers and wisdoms of the community. I am borrowing this as analogy to return to the topic of my presentation. This book has disrobed the student movement and has revealed to us at the core, the PYMN as a group of ordinary but patriotic students, coordinating the activities of the movement. In disrobing it, the PYMN has lost not only its power to discipline, in this case, the recalcitrant state, but also lost it mystic as the powerful group. But disrobing has a useful purpose. It allows us to understand its methods and their shortcomings, its strength and successes, its mistakes and foresights, and how it came to collapse. The lessons will then anticipate the future re-robing of the movement and how it can reinvent itself and become relevant in the current phase of the struggles in the country. If this book therefore sparks a conversation around the rebuilding of the student movement in Nigeria for its to become a key play in current struggles, for me, the book has paid for its production.