By Professor Gani Yoroms

Recently, I received an invitation to attend one of the CoDA High Level Technical Meetings on ‘Insurgency and Insecurity in Africa’. The letter was signed by the former president of Nigeria, Chief Olusegun Obasanjo. It was a high-level technical meeting of experts across Africa. The invitees were, among others, reputable scholars, military officers, securitocrats and bureaucrats from Africa and beyond. The venue was at the Olusegun Obasanjo Presidential Library, (OOPL), Abeokuta.

Chief Obasanjo, the chief theorist of ‘Kampeism’ in Nigerian politics, soldiers on with his OOPL, notwithstanding threats by critics threatening seizing and converting the edifice into a Nursery and Primary school at the earliest opportunity while admirers can’t hide their admiration for it and him

At the end of the day, the array of experts at the OOPL included Professor Abdoulaye Bathily, the Deputy Chair of the Coalition for Dialogue on Africa (CoDA); Dr Vasu Gounden, the Chief Executive of ACCORD, the famous African research and training Centre in Durban, South Africa; General Babacar Gueye, former Chief of Defence Staff, Senegal; General Alex Ogbumodia, former Nigeria’s Chief of Defence Staff; Professor Mohammed Salih from The Institute for Social Studies, Netherlands; Professor Col Larry Gbevko, former AU Special Representative in charge of Counter Terrorism; Mpho Molomo, SADCC Special Representative Mozambique; Prof Musambayi Katumanga University of Nairobi, and HE Dr Kamara leading a team from the AU headquarters from Addis Ababa and Dr Therese Azeng from the University of Yaoundé II, Cameroun. The Technical Advisory Team headed by Professor Adebayo Olukoshi of the Institute of Governance at the Wits University, South Africa provided a robust intellectual drive for the Chatham House conversation.

These were the resource persons who came to worry that most African countries seem to be focusing more on the military approach on containing insurgency. CoDA itself was established in 2009 by the African Union, African Development Bank, the African Import-Export Bank and the UN Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) as a platform for rigorous and frank debates, dialogues, open and exclusive conversations that are mutual and controversial. It is indeed a ‘continental Think-Tank and a change agent, with the mandate to take proactive stand on critical issues, defining new perspectives and interrogating most sensitive and controversial’ issues; and bridging ‘the gap between the research and policy making communities in Africa’. As already indicated, this particular meeting interrogated the menace of insurgencies and insecurity in Africa: ‘Counting the costs, Stemming the tide’.

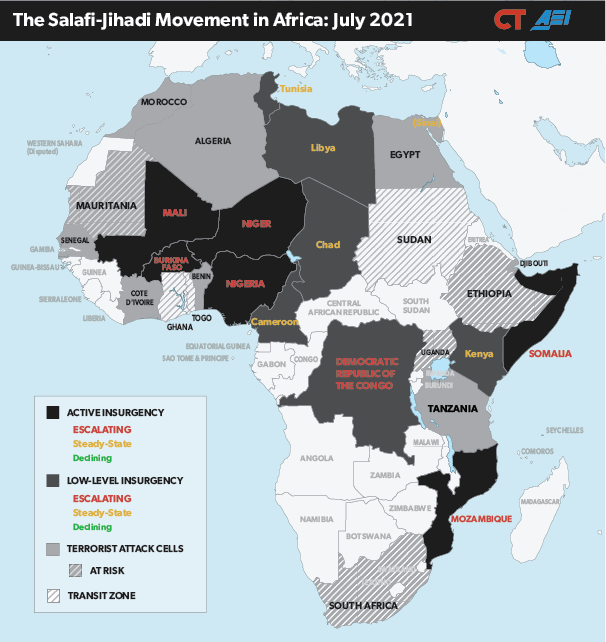

The rise and spread of insurgencies across Africa are appalling. The winding down of proxy wars at the end of the Cold War failed to usher in the dividend of peace and stability. Rather, Africa began to face ‘new wars’ where intra-states conflicts continue to provoke worse cases of genocide and ethnic cleansing in the Great Lake region, Burundi, Rwanda and the DRC. The trajectory of the post-Cold War world conflicts evolved largely from intra-state secular nature, deepened by the emerging histories and contexts of discontent, drawing inspiration from racial global extremism perpetrated by Al-Qaeda and later the Islamic State. Unfortunately, the diminishing capacity of the state to address these challenges have been aggravated by the levels ‘of poverty, festering inequality, systemic exclusion, marginalization, and increasing youth unemployment’. The ‘unraveling of the Libyan State following the NATO-backed overthrow of the Gaddafi regime’ further made the Sahel-Sahara and the entire West and Central Africa to be inundated ‘with flow of weapons as fighters of fortunes from Libya’, complicating the security challenges on the continent.

Key issues were, firstly, ‘how to effectively stem the growth and expansion of radical extremism on the continent, and secondly, how to re-establish the uncontested authority of the African state alongside its legitimacy to govern’. The worry of the experts was that most African countries seem to be focusing more on military prosecution as a solution aimed at combating the insurgents. More concentration on military approach to violent extremism has escalated with the amount of international supports through training, deployment of weaponry and recently as well as with the presence of military contractors and mercenaries.

Obasanjo a history of long involvement in African affairs

Therefore, in order to divert attention from military-focused solution, the high-level technical meeting drawn on expertise from within and outside the continent processed alternative thoughts that should effectively stem the spread of extremist violence on the continent. Particularly, it sought to expand the scope of solutions, allowing political, economic and social reforms to complement a pure ‘military -security response to insurgency’.

Steered by ex-president Olusegun Obasanjo, the technical meeting conducted an in-depth review of the origin of extremist insurgency on the continent, the strategy and record of military containment of the insurgency and how beyond military solution, African leaders and stakeholders must address the political, socio-economic, justice, reconciliation and reintegration efforts. We also recalibrated the role of subregional and continental organisations in a more integrated approach to managing and reversing insurgency in Africa.

The Olusegun Obasanjo Presidential Library (OOPL) is a fascinating place for serious minded intellectuals and policy drivers of the continent. Conceived in 1988, in the midst of oppositions from civil society groups led by the likes of Lagos lawyer, Femi Falana, the OOPL has become a magnificent edifice, placing Abeokuta on the international map. It is Obasanjo’s journey through history: ‘presenting the past, capturing the present and inspiring the future’. It houses the Centre for Human Security, the Institute for African Culture and International Understanding (approved by UNESCO) and a Youth Centre. A visit to OOPL by Femi Falana and his civil society critiques will beg for a pardon from Obasanjo.

As usual with OBJ (as Nigerians call him), he puts up a drama of curiosity. On the second day of the meeting, Obasanjo was nowhere to be found. Professor Bathily had to chair the first session of the day, on his behalf. He later arrived apologizing, as he was busy picking passengers with his tricycle in Abeokuta town, demonstrating that there is dignity in labour. The use of tricycle was introduced during his regime as a civilian president, to aid rural transportation. Obasanjo proved that age is just a number, as he remains active, lively and intellectually sound with knowledge and wisdom. His robust experiences will be a treasure to students of Political History. For the two days I spent in OOPL, OBJ had no military escort, only a police escort van and his Pajero car to move around the ancient city of Abeokuta.

Meanwhile, our meeting generated practical solutions, which Chief Obasanjo, the Chair of CoDA, would be delivering to the African Champion of Peace, the President of Equatorial Guinea, along with Professor Bathily. In this regard, I don’t have the right to reveal the recommendations. Hopefully, African leaders should have the political will to implement them.

On the last day of the meeting, my friend from Ghana, Dr Lartey, was delighted he visited the famous Olumo rock, leaving Nigeria with the lingering memory of Abeokuta.

The author is of the Centre for Strategic Studies and Research at the National Defence College Nigeria