This piece contends that there is a challenge of consolidation of the exceptionalism that can be argued for the designers, ideologues, activists, hand clappers and other minders or protagonists of the radical democratic politics that swept through Nigeria from the early 1980s to the mid-1995. An exceptionalist lore of what they did is sustainable for all those involved in that intervention in that there has been nothing like that in post-independence Nigerian in terms of a heightened attention to the dangers of arbitrariness, impunity, commandism and simplistic patriotism.

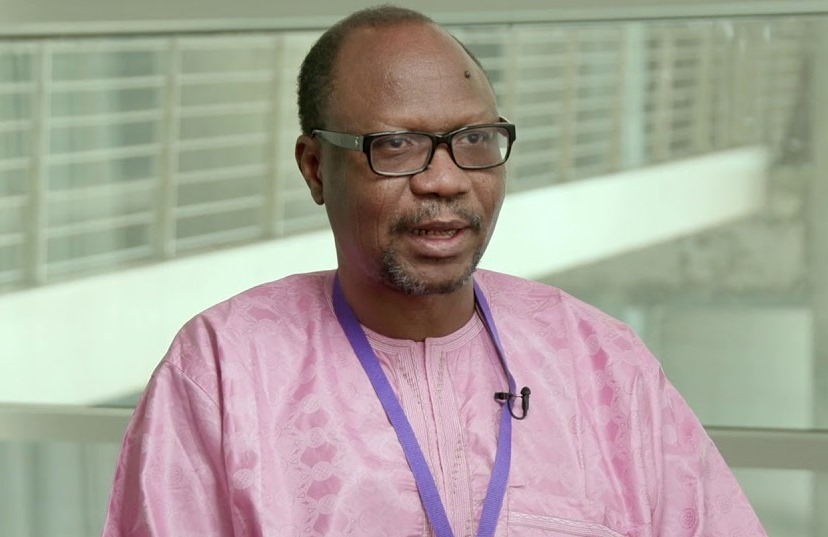

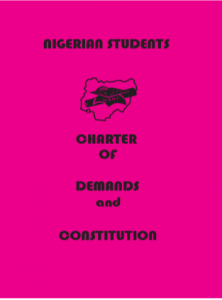

It is thus compelling to intertextualise their happy (as well as sad) moments such as the recent birthday of Dr. Kole Shettima, Director of the Africa Office of MacArthur Foundation, beyond the ritualistic into an empowering narrative of the collectivity. We can see the profundity of the sense of democracy shared by that collectivity by looking at, say, the NANS Charter of Demands or the ‘manifesto’ of the Women in Nigeria, all of which were foresighted calls for substantive democracy in Nigeria, with particular reference to inclusivity. Two features of this struggle provide further proof of the claim of exceptionalism. It was thoroughly pan-Nigerian as nobody knew anybody else in terms of religion or where s/he came from. Secondly, it was very early in the day, coming at a time when interrogating authoritarian attitudes were uncommon beyond the protest politics of few individuals and few middle class professional groups around Lagos. The military government was still seen as having come to correct the iniquities of the civilian politicians. It was the ‘manifestoes’ and bodies such as NANS, WIN, ASUU and so on formed to push various demands against commandism that were out on the barricades, ‘occupying’ and challenging the authoritarian critique of democratic norms and practices.

It is thus compelling to intertextualise their happy (as well as sad) moments such as the recent birthday of Dr. Kole Shettima, Director of the Africa Office of MacArthur Foundation, beyond the ritualistic into an empowering narrative of the collectivity. We can see the profundity of the sense of democracy shared by that collectivity by looking at, say, the NANS Charter of Demands or the ‘manifesto’ of the Women in Nigeria, all of which were foresighted calls for substantive democracy in Nigeria, with particular reference to inclusivity. Two features of this struggle provide further proof of the claim of exceptionalism. It was thoroughly pan-Nigerian as nobody knew anybody else in terms of religion or where s/he came from. Secondly, it was very early in the day, coming at a time when interrogating authoritarian attitudes were uncommon beyond the protest politics of few individuals and few middle class professional groups around Lagos. The military government was still seen as having come to correct the iniquities of the civilian politicians. It was the ‘manifestoes’ and bodies such as NANS, WIN, ASUU and so on formed to push various demands against commandism that were out on the barricades, ‘occupying’ and challenging the authoritarian critique of democratic norms and practices.

Above all, they fought these battles at great costs, be it in terms of campus protests and the massive expulsions and rustications that followed or street contestations and the invitation to the ‘Kill and Go’ squad from the Police it meant at the time. This response to earliest signs of the collapse of the Nigerian promise was distinct and exceptional, the closest to the radicalism of the generation that challenged colonial rule in various forms, producing independence.

Last generation of NANS leaders?

Memories of WIN and the moment in radical democratic campaign for gender inclusivity

Of course, time and tide waits for no one, including a diffuse collection that was attempting a generational statement even as differing in age as their composition. And the question today is the possibility of how they might kill the snake which it seems they merely scuttled before they were dispersed, displaced and/or disorganized by global as well as local tides, particularly the end of the Cold War and the June 12 crisis, respectively. With many of them dead, (Emma Ezeazu, Chima Ubani, Tajudeen Abdulrahameem, Bala Jibrin, Thompson Adanbara, Bamidele Aturu readily come to mind) and most well beyond 60, this can be an ‘injury time’ for the question of consolidation of an exceptionalism. In other words, beyond the generalities already referred to, what outcomes corresponding to the exceptionalism in question can we still see or talk about?

The argument here is that there is a project of ‘Writing Corruption’ courtesy of MacArthur Foundation that speaks to the legacy of this exceptionalism or which can be strengthened to speak to the legacy. Whether the project is Dr. Kole’s own idea or came to MacArthur Foundation from some other source, it fits into the framework because, as the Director of the Africa Office, Dr. Kole is automatically the chief superintendent of the organisation’s support for the campaign. And it is fit to call the campaign a case of writing corruption because it relies on a representational practice of power towards a discursive constitution of the phenomenon of corruption as a fundamental contradiction. The protagonist-antagonist contestation inherent in such concerted and organised representation means that the campaign can easily end up reconfiguring the power relations around corruption in favour of those against it in the society. Should that happen, then the question of what power does automatically arises. In spite of the instability of hegemony, a revolution against corruption in Nigeria would have been accomplished to everybody’s chagrin.

The late Dr. Yima Sen

Femi Falana (SAN)

In other words, something is going on there that speaks to the novelty typical of the exceptionalist lore of the political generation being talked about here. It is not clear if other members of the generation appreciate this, seeing as many of them are still hooked on to the Enlightenment modernism as to be aware of the break in social theory in favour of textuality. It is even more unclear if the intellectuals and foot soldiers of ‘Writing Corruption’ have situated what they are doing in the paradigm of representational practice of power and whether the objectivist practice informing their narratives can guarantee discourse productivity. Or if they consider that it is not (social) influencers or the media but the structural, institutional and agentian context in which mediated texts can produce the kind of associative chains that can undo corruption.

Other than such observable limitations is whether the conceptual constraints on the anti-corruption war have been carefully reflected upon. For instance, does it make sense to expect that those who go into political offices as ministers, governors, chairmen of Boards, presidents and local government chairmen, amongst others, will not be tempted to steal but content with creating and supervising the conditions of accumulation for their brothers, friends, age and school mates who chose to go into business? It is simply a faulty paradigm which will never work but something the anti-corruption warriors in Nigeria rarely talk about. It is the same thing as the wrong headedness in allowing for looting so that culprits can be arrested, tried and jailed. Why not make it impossible for public resources to be looted in the first case, an option which is cheaper anyway.

As real as these constraints are, reality is still what we make of it. Considering the success in the deployment of textuality in the conduct of recent wars which is basically what the ‘Revolution in Military Affairs’, (RMA), refers to, the strategy of mediated representation of corruption is still a viable one if systematically handled. ‘Writing Corruption’ as is presently being experimented with support from MacArthur Foundation presents even adherents of anointed or pre-given bearers of the ‘revolution’ an opportunity for leveling corruption in Nigeria which will be an accomplishment corresponding to generational exceptionalism. It is true corruption narratives are being used as an instrument for disciplining Nigeria in global politics when it is abstracted and presented as if it is the only thing happening in the country. Empirically, however, looting of public treasury is a major dimension of the crisis in Nigeria. Victory over it cannot be anything less than a revolution. And we can talk of a ‘Revolution in Anti-Corruption’ instead of ‘Revolution in Military Affairs’ should ‘Writing Corruption’ produce that outcome.

A critical ‘Happy birthday’ then to Dr. Kole Shettima for successfully adding one more year to his age but also for putting something on the table. The expectation is that many others will be offering something unique soon too, particularly Femi Falana, (SAN). The hope in his case is that the generation will not be making the same mistake it made regarding the late Dr. Yima Sen. Yima was, in every sense, a presidential material from that generation unless it was looking for angels. He tried but too little too late. Or something like that. Falana is not only a signifier for unbroken operationalisation of the tradition, he is so informed about what is going on in his environment and has got the technocratic verve that is not common. Surprisingly, he is not out there as a local government, gubernatorial or presidential aspirant when other funny creatures are and are being taken seriously. Perhaps, like Prof Attahiru Jega, he is being cautious and awaiting group decision. That’s great and perhaps an understandable approach in a complex polity such as Nigeria but Nigeria is not an entity cast in stones. Those who seek to change it must advance to be recognised and in such an irresistibly distinct manner that leaves no one in doubt that as the advertisement goes, when it is not panadol, it is not the same thing as panadol!

- Adagbo Onoja