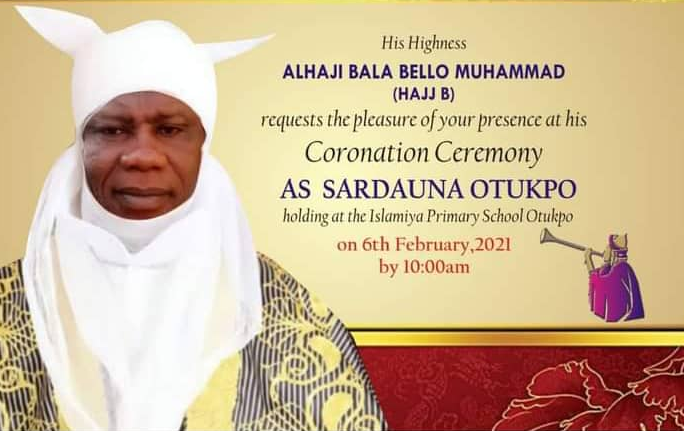

It was no fun waking up to a Whatsapp photo from an otherwise cool and problem free individual, drawing attention to something that is being scheduled to happen in Otukpo town in Benue State. He is not disturbed but he was drawing attention to a plausible flashpoint of 2021. His message was well taken. It actually brought to mind Bosnia in old Yugoslavia.

Bosnia was the signature space in the European imagination of the post Cold War – a peaceful place inhabited by almost every identity imaginable – Christians, Muslims, diverse ethnic groups. But it was the place that exploded in the post Cold War. Identity exploded it and identity decided the question of how to manage putting it back.

Insular narrative or clash of particularism with universalism?

Far away from each other in territorial terms, Otukpo is, however, very close to Bosnia in terms of composition. Otukpo is diversity personified in Nigeria – a confluence of identities – from Yoruba to Igbos to Hausa-Fulani, Muslims, animists and a powerful Catholic presence. Yet, Otukpo has never witnessed what is popularly called ethno-religious conflict. It was about to slip into a cultic holding space but it seems Idoma leaders realised that, if allowed to slip into a space of violence, it would take so long to recover. And that such would be unaffordable for her only township with potentials to move on to the strategic status of an Onitsha, Aba, Enugu, Jos, Kaduna and even Lagos.

The similarities between Otukpo and Bosnia in spite of the distance between the two leads to another reminder from Ernesto Laclau’s surprising statement in his book titled Emancipation(s). There was something surprising in the statement, given Laclau’s extraordinary activism as a Peronist before he crossed over to political theorising and a phenomenal academic life to his death.

Said he in the book which was already in its third edition by 2007, “If we wanted briefly to characterise the distinctive features of the first half of the 1990s, I would say that they are to be found in the rebellion of various particularisms – ethnic, racial, national and sexual – against the totalizing ideologies which dominated the horizon of politics in the preceding decades. … Both the ‘free world’ and the ‘communist society’ were conceived by their defenders as projects of societies without internal frontiers or divisions”.

He goes on to add that “it is the ‘globality’ of these projects that is in crisis”, especially the conflict between particularism and universalism that he could see in the period after the Cold War – ethnic violence in Yugoslavia, populism in Western Europe and the racist politics that stretched to immigration thereupon; expansion of multicultural contestation in North America and the end of Apartheid in South Africa.

He saw a dangerous and difficult confrontation between the two projects. Typical of him, he believed that the two could be mediated but only by his formula of bringing about a ‘coalition’ that can create a hegemonic narrative that can guarantee radical democratic politics. That is a ‘coalition’ not in the Leninist sense of alliance but what he calls a ‘historic block’ that modifies but does not necessarily nominalise any of the groups signifying the particularisms – ethnic, nationalist, sexual, environmental and similar protesters of what is keeping them from freedom. It is in this sense that his theory of articulation of incommensurable groups into a ‘historic block’ is called post-Marxism by both himself and his critics because he doesn’t see how the traditional working class that orthodox Marxism relies upon can still mediate the conflict of particularism and universalism through Jacobinism.

The success of his strategy in Latin America remains overwhelming. It was thus a very interesting moment when Muhammadu Buhari began singing that the events in the old USSR had educated him on the imperative of democracy and democratic politics. It was understood as a signal that either the man had been, keenly, watching developments in Bolivia in particular or had intellectuals around him and debating all such developments as they relate to the crisis in Nigeria. Or that, in his quest for power, Buhari might have been silently studying someone such as Ernesto Laclau phenomenon, from his radical activism in Argentina in particular, his relocation to Europe and theoretical insurgency for radical but democratic politics and his profound influence across the world. That explains why it was so disappointing that when ethno-religious violence broke out here and there under Buhari, all he could say was to ask people to learn how to live with each other.

The late Prof Ernesto Laclau

A geopolitical moment had unfolded in human history with the collapse of the Soviet Union without a shot fired at it from outside. The ideological frameworks that held the world together since the Cold War began in 1945 had collapsed. Everything was going to be understood as new, especially the terms by which people hitherto related to each other. So, Putin, for instance, wasn’t joking when he said that the breakup of the Soviet Union was the greatest tragedy of the 20th century. He might have meant how it affected Russian great power calculation but which is not necessarily different from the impact of that collapse for global fate. So, asking people to learn how to live with each other was either a manifestation of an I – don’t’ – care attitude or just lack of attention to what is going on in the world.

But, it was far from the president alone. The political parties, the think tanks, individual intellectual referents in Nigeria and the radical left have not been up to it in terms of the building of the ‘historic block’ that could get involved in the mediation of the clash of particularisms and universalism. Instead of doing that, everyone runs to his or her cultural backyard, does what s/he as a radical activist or nationalist should NOT have done only to emerge to accuse others of doing ethnicity or religious insularism. Or to argue that Others are not patriotic enough.

To manage 2021 in Nigeria would require a coming to grips with the challenge of bringing into being a Nigerian variant of a ‘historic block’, no matter how poorly done. There have been a lot of webinars/Zoom conferences of differing groups trying to break boundaries and come together. From the lessons of June 12 struggles, that approach would not work because it is not the same thing as the politics of creating a hegemonic or historic block made up of incommensurable groups pitched against a defined ‘evil’ other.

It is only when that comes into being that the poster from Otukpo may be contained. Otukpo is mentioned here not as Otukpo per se but only a signifier for the age of rising particularisms the type the world has seen in Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Burundi, Liberia, Somalia and so on. This is because it is not that people no longer know how to live peacefully with each other but people are enacting completely different narratives by which their lives makes sense to them. And this trend is made worse by a major new development. That is the digital or informational nature of contemporary capitalism. Here, it is exactly the problem as Chris Gray identified it in his book, Postmodern War. That is where he was saying that information has become the central sign of postmodernity “as a weapon, as a myth, as a metaphor, as a force multiplier, as an edge, as a trope, as a factor, and as an asset”.

Gray is only empirically right in that digital communication has helped superintendents of Otukpo, for instance, to send a protest signal but it was not information capitalism that drove the impulse. It is exactly what Laclau put his finders: the clash of particularism with universalism. As far as the guardians of orthodoxy are concerned, the Otukpo-ness of Otukpo is under siege from the universalising narrative of right of free movement. It is much, much more than something peculiar to Otukpo. It is also there in how the Nigerian military has been unable to route Boko Haram up to this moment. And in any other issues one takes in Nigerian politics today. Yet, this is something that neither pacificism nor conflict avoidance can cure.

Is it not surprising that only the few countries that have been able to come to grips with the crisis of meaning created by this geopolitical moment since 1991 that are making progress, as exemplified by the few of them that were able to contain Covid-19 better than others? This is what makes the current situation in Nigeria quite troubling. It is not Buhari’s ailment that is as much the problem as the regime or the president’s lack of a grand logic of power that is self-aware of the global context of power and authority in Nigeria. If such a grand essence were there, the physical presence or absence of the Buhari person will not be of any fundamental consequences. Persons groomed in that logic of power should be able to, faithfully, operationalise its key constructs. For that reason, there was a flicker of the hope in the coming of Prof Ibrahim Gambari, everything considered. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that he is in the inner room of the Buhari power. Now, things are reaching a level where the narrative of a sinister plot is surfacing.

Well, here is 2021. How it goes depends on how it is received! In all cases, whatever anyone does should be based on reckoning with the fact that there are millions of Nigerians who have to go out every day to be able to feed themselves and their dependents. Nobody should create any situation impairing the life of such people who usually have no say in the decisions made by the vocal and the powerful. Those genuinely eager to contribute to the resolution of the crisis should focus their gaze on the strategies for mediating the on-going clash of particularisms and universalism in the ways the clash is manifesting in Nigeria.